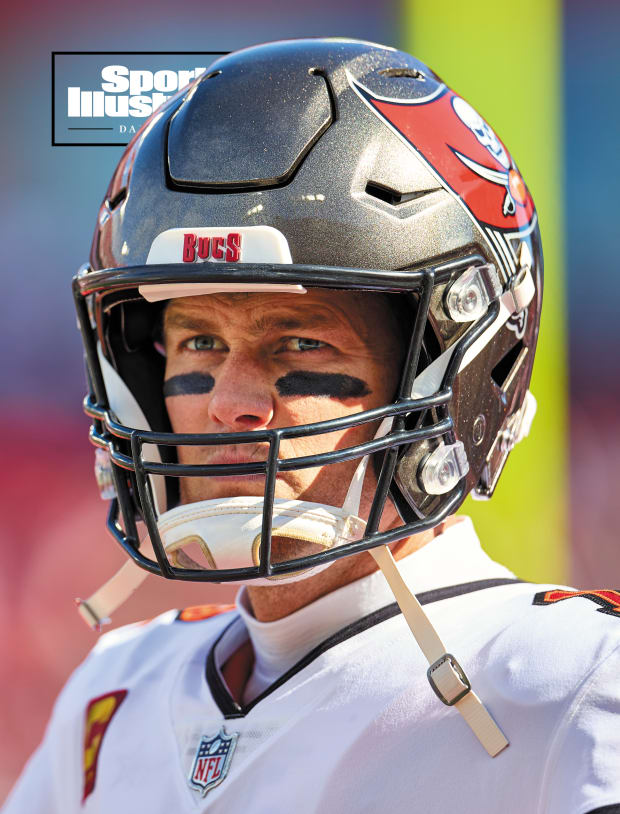

There was always something about the way Tom Brady stood there in the pocket, feet set just beyond shoulder width, symmetric; spaced perfectly, body upright, straight but fluid; always, both hands on the football. He looked like a statue, or an NFT, less human and more form of art. But Brady wasn’t, as they say, born to throw footballs better than anyone on earth. He was born to pursue throwing them with every ounce of focus, energy, obsession and delusion he could muster.

I’ve written about star athletes over the past 20 years and am often asked about others I’ve profiled. I’ve fielded more questions about Tom Brady than Aaron Rodgers, Roger Federer, Manny Pacquiao and all the rest combined. They want to know the secrets, the routines, whether he really eats avocado ice cream. One prominent NFL quarterback—I didn’t clear this with him, so I won’t use his name—wondered, simply: Where does Brady find the time?

Funny he should ask. Because lately, when thinking of or speaking about one Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr., the concept that keeps surfacing is: balance. In some ways—in the pocket, for instance—no one possessed more. On balance, in balance, forever balanced, that was Brady’s football career, an ethos. But staying in balance while playing football required an imbalance everywhere else.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Brady went to Tampa three seasons ago at least in part because he wanted to find more balance. He wanted to be closer to his oldest son, Jack, who lives in New York. He wanted to be closer to his then wife’s family. He wanted a new balance, wanted to spend more time at home. But then he retired last offseason. Retired when he wasn’t certain that he wanted to stop playing. It happens. But many close to Brady saw him stepping away for his family only to change his mind and return for his other family, and they believed—they knew—that it would create problems for him at home.

Confidants are careful in regard to what they want to say about the past six months. Know this: They have been difficult. Brady has feelings, emotions, fears, just like everybody else. He played this season in the most public spaces and with the heaviest of hearts. He played well, too. The long break he took during training camp that seemed unusual? It was. Brady needed to get his mind right to remain at his best for his teammates, the Bucs and everyone depending on him.

Then, divorce. Then, the Bucs’ descent, a season lost to injuries and confusion, a mess. For most of the season, Brady just looked sad. He looked tired. He looked like a middle-aged man trying to make sense of what had happened, what had not happened, what he wanted to happen and what would happen. There were so many unknowns.

According to those same people, Brady was weighing whether he would retire, finally, for good, even until this week. He had gone to Tampa to find a better balance and win another ring. He got the latter but not the former. His football pursuits cost him in ways he hadn’t truly foreseen. Combine that with not winning or excelling or meeting his own ridiculous standard—let’s not get wild here, the dude still finished third in the NFL in passing yards, after only Patrick Mahomes and Justin Herbert—and, eventually, he decided it was time. He called the Bucs early Wednesday morning, around 6, and told them he was done. Other franchises were interested, pursuing him like defensive ends have for more than 20 years, and finding similarly limited success. He would not have gone to San Francisco or Las Vegas, he told friends, or anywhere else except for Tampa, if he played another season. And for what it’s worth—this is little more than an educated guess here—he will not.

Brady is a present father. He cares deeply about his family and his friends. He built a brand and a business and, eventually, an empire. He’s not the gridiron cyborg that often is portrayed. He’s a real person, underneath the fame and the frame that grows skinnier as he ages. And yet, he also is that, exactly that, when accounting for some nuance. He would never have been Tom Brady if he didn’t avoid strawberries and other foods he considered inflammatory, if he didn’t sleep in recovery pajamas, if he didn’t work out until Super Bowl Sunday every season even if he wasn’t playing in the game, which wasn’t often. His in-season schedule ran through that day, which meant he found a field and met his body coach and did what he has always done. He prepared.

He called his parents Tuesday night and again early Wednesday morning. On the second call he told them, “I’m going to make the announcement this morning.”

They responded as parents, because, to them, he’s still Tommy, not some sort of football god. “Great,” his father, Tom Sr., says he responded. “This is Chapter 2.”

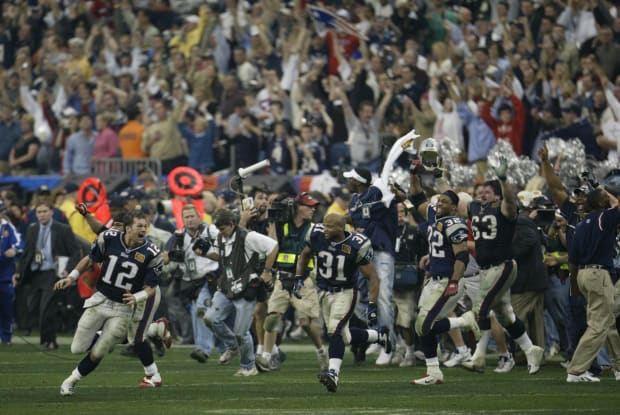

It was hard for them to process anything, let alone everything that had transpired. Highs so high—seven rings! Immortality! The GOAT of all GOATs—they sometimes felt like they were living on another planet. Contrasted by lows so low—his mom’s cancer; real controversies (Spygate) and dumb ones (Deflategate); the split from New England—they threatened to overwhelm. How could anyone make sense of everything?

John Biever /Sports Illustrated

Throughout all of that, it seemed like Brady found joy in that process, not to mention fulfillment. Process was his meditation, how he transcended everything and everyone else. His pursuit wasn’t for them, or for glory, though. That stuff was secondary. It mattered but not as much as most would think it mattered. Brady pursued perfection because he needed to, had to, somewhere deep, deep, deep inside. This wasn’t a pursuit so much as a craft, the only way he could exist. Nor was it simply part of him. It was him.

That distinction is important. At least 100 athletes have sat across from me and delivered some version of the same concept. They’ll say that their sport does not define them, that they play football/basketball/baseball/tennis, that they drive/race/box. But that’s not them, they insist. They’re parents, siblings, friends, entrepreneurs, philanthropists. They just happen to play sports because they’re good at them, because turf life beats a cubicle existence.

Brady is all those things. But football does define him. Or did, anyway. Perhaps he’s different, more fixated, borderline possessed. Or maybe he’s the only person willing to tell the truth.

The first time I wrote about Brady’s routines, way back in 2014, that body coach, Alex Guerrero, went right at the same notion. TB12 wasn’t the sprawling network of centers, books and products it has become. This was the early stage of Brady as TB12, a brand. “Football isn’t what Tom does—football is Tom,” Guerrero said.

Perhaps that’s the only way mere mortals can relate to him. Even Brady must make choices, must consider his life in all facets and how they fit together, weighing what matters now and what will matter later, with pursuits that stand in perpetual contrast. Even Brady is human. He’s certainly way more human than he’s given credit for. He wants what everyone wants: happiness, gratification, everything; a full, well-rounded life.

Brady is also 45 years old, the father of three children and, until last fall, a husband working his ass off, straining his wife’s patience and trying to find the time. He was us, people faced with the same factors and struggling to make them fit, to make us whole. And that was weird, because he’s him. He turned 45 in August, early into his 23rd and ostensibly final NFL season. At one point, he reminded the journalists who were pestering him about his personal life of his age. As any middle-aged parent knows, Brady was spot on there, too. He said, more or less, s--- happens, to everyone. Amen.

Brady, of course, is not us, not in the most significant way. He has spent more than half his life in pursuit of football glory, trying, then trying harder, then trying something else. What he did tugged at his soul. It was his soul. But what he wanted to do, later, when he could find the time—which he did find more of over the years—tugged at his soul, too.

The perfectly balanced quarterback never found the perfectly balanced life. Who does? The latter doesn’t really exist, even for Tom Brady. His in-pocket balance led to much more than he ever could have reasonably expected, to Lombardi Trophies and championship rings and NFL records that won’t be broken, for a long time, if ever. But that football balance cost him, too.

The video Brady posted felt authentic. He looked like a man caught in a moment of great significance, a pivot point between what has fulfilled him and what he hopes will soon. The transfer from one to the other will unfold over the coming weeks, months and years.

Zoom in past the scenic beach background and the windswept hair. What stands out isn’t that perfect jawline or those penetrating eyes that scanned NFL defenses for more than two decades. What stands out is the sadness in his face, which must owe to what football means to him, its intrinsic place in his existence. Beyond the career-over grief, though, there’s contentment. “I wouldn’t change a thing … love you all,” is how Brady seems to give voice to that finality. But his face is more indicative. It says, It’s time.

“I couldn’t be more proud of him or how he comported himself,” Brady’s father says. “He’s such a great son. Such a great guy. Great dad. He’s selfless.”

Alex Smith woke up to the video Wednesday morning. It transported him back, immediately, to 2021, when, after the greatest comeback from injury in NFL history, he retired after 16 seasons. In Brady, at that moment, he saw himself. “The video was real,” Smith says. “You could tell this is something that had been weighing on him—and maybe there was some relief in putting it out there.”

The hardest part for many, Smith says, is that final moment, when the decision calculus shifts from maybe I should do this to I am going to do this to I am definitely retiring. He imagines that it must have been more difficult for Brady, because of the unprecedented nature of his career and the unprecedented nature of his approach to throwing footballs. Still, Smith understands the burden, what can feel like the world’s heaviest weight. Later Wednesday afternoon, he would partake in the Pebble Beach Pro-Am. (See? Retired life ain’t bad.) “I’m happy for him,” Smith says. “There just seemed to be some closure. Like he was saying goodbye to the game. And I know that was part of my deal.”

Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

In recent years, Smith followed Brady’s final career stage, the move from New England to Tampa. He saw the seventh title, the seamless transition, the same dominance deployed in a different city and different conference. Brady, he thought, revealed more and more of himself. He came across as funny, self-deprecating, self-aware and, above all, human. In hindsight, maybe that was a sign of the pivot point ahead. The End. No 80 for Brady, not in real life. More imbalance in his honed and stretched and endlessly hydrated muscles. Less imbalance everywhere else.

It's far easier to embrace this retirement than the last one, and that owes to Brady’s expression and the ease in his delivery. The question that lingers: Can he find a better balance? And, if so, how? That search starts now, and, just a guess here, it will start with his idol, parenting model and a main soundboard: his father.

Tom Sr. once told me that, after his son’s first Super Bowl triumph, Tommy gave him the ring. Senior gave it back. He was staying with his son but soon left. Tommy called him later and told him to look inside his suitcase. He had packed the ring into his father’s carry-on. That moment was pure, in the fathers-and-sons sense, and while Brady gifted his family with moments and memories he will cherish forever, it always seemed like he envied his old man. His grandchildren, Brady Sr. says, provide his son with “great amounts of joy.”

Senior heard something recently, on one sports show or another, about how Brady should return to San Francisco, to play for the team he grew up rooting for, with his dad attending home games. Perhaps he could help the 49ers win their first Super Bowl since his childhood. And—his father laughs at this—he could do that in front of his “quite elderly” parents. They would have loved that. But they’re glad that he retired, too. They don’t want Tom Brady, seven-time Super Bowl champion, so much as they want Tom Brady, happy and at peace with his decision. More than three decades of football—including 23 in the NFL, five in college, four in high school—is enough.

If anything, they need to figure out what to do on Sundays now in the fall. For decades, Brady’s parents watched not just him but followed the rest of the league closely. Every other game impacted their son’s chances. “A magical roller coaster,” his father calls it—a ride that seems to have, at long last, stopped.

“If I’m being honest, we’re going to be totally lost,” Senior says. “But that’s O.K. Tommy loved football, respected the game and admired his competitors.” His father begins to list them: Brees, Manning, the other Manning, Big Ben, Rodgers, Mahomes and the rest. “That’s what he does,” Senior says. “That’s who he is.”

The temptation here is to tally up Brady, to paint him by numbers: seven Super Bowls, three league MVPs, five Super Bowl MVPs, 15 Pro Bowl nods, 89,214 passing yards (most ever), 649 regular-season touchdown throws (same), 13,400 playoff passing yards (same), 88 playoff touchdown passes (same). He had a Hall of Fame–caliber career in each of the past three decades. He ate a lot of avocado ice cream.

But anyone focusing exclusively on Brady’s focus—football—is missing what he struggled with these past few years. There is more to him than that. He won’t “play forever,” as he told me back in 2014. But it will seem like he did, as he pivots into his real forever, as he tries to beat not Joe Montana or Peyton Manning but the other Tom Brady, the original, his dad. (By the way, Brady Sr., a chairman of an insurance firm, has not yet retired. Career longevity runs in the family.)

“He’s in the right place,” Brady Sr. says. “I’m sure that in September, October, November, he’s going to really want to play. He’ll have some buyer’s remorse. I mean, Gronk is talking about coming back! At the same time, he loves his kids and wants to spend time with them.”

He pauses, then resumes. “I am pretty certain that there’s a finality to his announcement today. He’s had a good thing. And now he’s gonna move on to another good thing.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

I woke up Wednesday morning to something like 500 text messages related to Brady and his retirement. I had to write. But I paused at 7 a.m., when I typically wake up my 5-year-old son. I told him the morning would be dedicated to a work emergency.

“Who is Mr. Brady?” he asked.

“He played football for a long time. As well as anyone who ever played. But this morning, he said he won’t play football anymore.”

“Why did he play so long?”

“Because he loved it. Because he could. Because it mattered to a lot of people. Because it mattered to him.”

Imagine how many parents had that kind of conversation with their children. Imagine how many will. The best part, though, is that Brady can tell his own kids. He can tell them why he fell so deeply in love with preparing to throw footballs. And he can tell them about balance, the kind that’s lost and the other kind that’s found. Maybe he’ll add that, in searching for this elusive concept, he knew he could step away. But stepping away wasn’t as important as what he stepped toward.