Over the past 50 years, Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court have increasingly diverged in how they view the laws that relate to Indian tribes. Congress has passed significant legislation that expands tribal governments’ sovereignty and control over their land, while the Supreme Court has ignored and reversed long-standing principles of federal Indian law that protected tribal sovereignty and prevented the states from exercising authority in Indian country.

This trend at the court was seen most recently in a ruling from late June, which, as one longtime court observer put it, wiped away “centuries of tradition and practice.” Justice Neil Gorsuch scorned the ruling in his dissent: “Truly, a more ahistorical and mistaken statement of Indian law would be hard to fathom.”

From my perspective as an expert in federal Indian law, the most recent case is noteworthy because it says that states may exercise authority in Indian Country even without express congressional authorization. For centuries, that was not the case.

Here’s the background:

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress authority over Indian affairs, including the power to diminish and restore tribal powers. Since 1885, Congress has granted authority to federal prosecutors to try major crimes committed in Indian Country, such as murder and rape, in federal courts. Tribal governments can probably try these crimes, but Congress has limited the sentences tribal courts can impose on convicted offenders. As a result, the federal government has been the primary enforcer of criminal law in Indian Country for a long time.

With limited exceptions, the Supreme Court has interpreted the Constitution to say that the states do not have authority in Indian Country unless Congress expressly grants such authority. Congress has rarely authorized states to exercise authority in Indian Country, and it has required tribal consent before granting any such authority to a state since 1968.

The background to this allocation of authority is a long history of states’ trying to usurp tribal sovereignty by asserting jurisdiction over Indians in Indian Country. States’ early attempts to govern Indians led to violence and encouraged the Founding Fathers to grant all powers over Indian affairs to the federal government in the Constitution.

The latest case

Yet on June 29, 2022, in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, the Supreme Court ruled that Oklahoma could prosecute Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Indian, in a case of neglect and abuse of an Indian child on the Cherokee reservation. By ruling that Oklahoma may prosecute non-Indians for crimes committed against Indians in Indian Country, the court granted states authority in Indian Country, even though the relevant law does not expressly authorize states to do that. It was a serious blow to tribal governments across the nation.

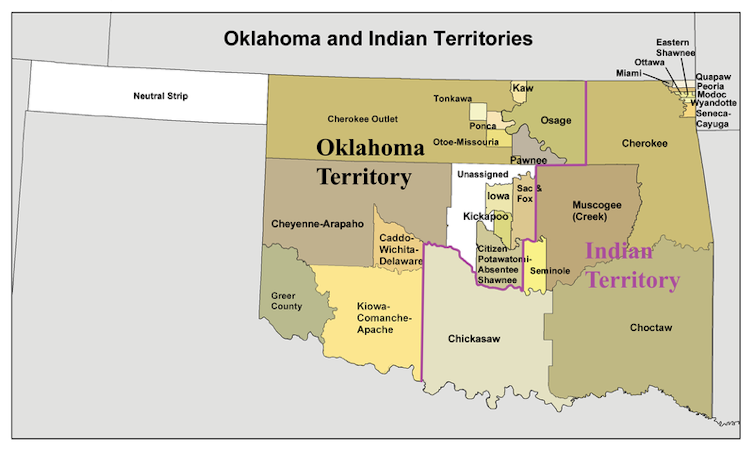

The Castro-Huerta case arose out of the state of Oklahoma’s prosecution and conviction in 2015 of Castro-Huerta in the neglect of his legally blind and developmentally disabled 5-year-old Cherokee stepdaughter by severely undernourishing her. While his appeal was pending, the Supreme Court in 2020 decided McGirt v. Oklahoma, which held that the Muscogee Creek reservation in Oklahoma is Indian Country. That ruling meant that federal criminal laws applied to much of eastern Oklahoma as Indian Country and enabled the federal government – instead of the state of Oklahoma – to prosecute crimes committed by and against Indians there.

Courts have since held that the lands in Oklahoma of five additional tribes – the Cherokee Nation, the Choctaw Nation, the Seminole Nation, the Chickasaw Nation and the Quapaw Nation – also remain Indian Country. This meant that the relevant law, enacted in 1817 and known as the General Crimes Act, extends federal criminal laws even farther into eastern Oklahoma and enables federal prosecution of crimes committed against Indians there.

In light of the McGirt decision, Castro-Huerta claimed that only the federal government had the authority to prosecute him, not the state, because his crimes occurred against an Indian within Indian country.

Before this case, no state had argued that states, in addition to the federal government, had criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country under the General Crimes Act. Yet the state of Oklahoma made just this argument in response to Castro-Huerta’s claims. It also actively resisted implementation of the McGirt decision and asked the Supreme Court to reverse it over 40 times.

Two visions of federal Indian law

Conflicts between state and tribal governments are not new; states have long tried to assert power – often violently – over sovereign tribes. In 1790, the first Congress enacted the Trade and Intercourse Act, which confirmed federal government power over almost all aspects of Indian affairs. Criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country has been considered federal and tribal ever since, with only one limited exception, for crimes committed by non-Indians against non-Indians.

In 1832, the Supreme Court interpreted the U.S. Constitution as giving Indian affairs jurisdiction exclusively to the federal government and confirmed that state law had no force in Indian Country without specific congressional authorization.

The majority in Castro-Huerta departs from this long-established premise, concluding that state jurisdiction should be presumed absent congressional action to preempt it. The court then rejected Castro-Huerta’s claim that Oklahoma did not have jurisdiction over non-Indians committing crimes against Indians in Indian Country.

The dissent presented a very different view. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that the U.S. Constitution, Congress and the court’s own previous precedents treat tribes as separate sovereign governments. He focused on Congress, which has authorized only a few states – not including Oklahoma – to exercise criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. Gorsuch concluded by calling on Congress to correct the outcome of the decision and restore the presumption that states do not have authority in Indian Country absent express congressional authorization.

Congress’ support of sovereignty

Castro-Huerta is the most recent example of a growing divide between the Supreme Court and Congress over federal Indian law.

As my research shows, Congress has actively remade federal Indian law over the past 50 years. Members of Congress introduced almost 8,000 bills related to Indian affairs from 1975 to 2012. Congress enacted almost 13% of them – double the percentage of bills enacted by Congress generally.

Congress has supported tribal sovereignty through legislation that has promoted tribal legal systems, ensured tribes operate effective child welfare systems, treated tribes like states for tax and environmental purposes, entered into compacts with tribal governments to provide federal services to their communities, and restored tribal criminal jurisdiction over specific crimes committed by non-Indians in Indian Country. At the same time, it has refused to grant states authority in Indian Country absent tribal consent.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly limited tribal sovereignty, often when confronted with conflicting state claims of authority. It has not deferred to Congress as the Constitution requires but has usurped lawmaking power for itself. The result has been confusion within federal Indian law and on the ground in Indian Country.

Nowhere has this divide between the court and Congress’ visions of federal Indian law been more evident than in the criminal law context. Congress has repeatedly limited Supreme Court decisions that interfere with its framework for criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. In doing so, it has promoted tribal jurisdiction, not state jurisdiction, over alleged criminals in Indian Country.

As the primary lawmaker in the United States, Congress can enact laws to reverse or change certain Supreme Court decisions. In 1991, Congress overturned the court’s decision in Duro v. Reina and recognized that tribal governments have criminal jurisdiction over non-member Indians. More recently, in 2013 and 2022, Congress started to reverse the court’s decision in Oliphant v. Suquamish Tribe by restoring tribal authority over nine crimes committed by non-Indians in Indian Country.

Castro-Huerta arose from a dispute between a state government and the federal and tribal governments but it reflects a larger conflict between Congress and the Supreme Court over federal Indian law. It is unlikely that the decision will resolve either. It may be time for Congress, as Gorsuch urges, to step back in. But even that may not end the conflict.

Kirsten Matoy Carlson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.