Larry DiMarzio doesn’t do an awful lot of interviews. Which is a shame because he’s one of the most storied and rightly famous electric guitar pickup makers and tone innovators in the world.

Cutting his teeth in the late ’60s and early ’70s, repairing guitars for the busy and demanding pro guitarists of New York, he soon learned that professional guitarists needed pickups that offered higher performance than the factory units being made by Fender and Gibson at the time. After a stint working for Bill Lawrence, he went on to almost single-handedly invent the mainstream pickup market.

His first foray into designing original pickups yielded the FS-1 – an eponymous ‘Fat Strat’ pickup designed to correct the tendency of traditional Strat bridge pickups to sound shrill and thin, which was subsequently adopted by players such as David Gilmour of Pink Floyd.

But it was his next creation, the fiery but surprisingly versatile Super Distortion humbucker, that really put DiMarzio on the map – and today his pickups are used by everyone from Steve Vai and Satriani to Nita Strauss and Andy Timmons.

In a rare one-to-one interview, we ask Larry about his philosophy on getting great tone and learn how the Super Distortion kicked down the door of the ’70s guitar scene.

Before you founded DiMarzio, you cut your teeth at New York guitar-repair centre Guitar Lab. You’ve said that one of the commonest mods you were asked to do was retrofitting Les Paul Deluxes with full-size humbuckers. What was driving that, in your opinion? After all, mini-humbuckers can sound pretty good…

“Most guitar players – the hip guitar players and the guitar-repair people – accepted and recognised the fact that Gibson was not paying attention to what we wanted at that time. Nor Fender, for the most part. Jeff Beck and, in particular, Jimmy Page were playing Les Pauls, so suddenly everyone wanted a Les Paul.

“So what does Gibson do? Did Jimmy Page’s guitar have mini-humbuckers? No! [Laughs] So I would say that on average, we were doing several conversions of mini-humbucker Les Pauls to full-size humbuckers a week during the time I was at the Guitar Lab. We’d take the original out, rout the hole bigger, drop the new humbucker in.”

The other in-demand mod back then was removing standard Tele neck pickups and replacing them with full-size humbuckers. How did beefing up factory Fender tones lead to your debut design, the FS-1 ‘Fat Strat’ pickup?

“I remember [Guitar Lab owner] Charlie LoBue was really happy with himself because he had bought a batch of Firebird pickups. Up to then, we had been installing full-size humbuckers in Teles, which were totally mismatched to the bridge pickup.

“Also, the strings don’t line up… But we took the neck pickups out, put humbuckers in, and accepted the fact that it worked – and yet it didn’t really work. It was a half-solution. And so Charlie was really happy because he’d contacted Gibson and apparently they had a box of old [non-reverse] Firebird pickups that were never installed in guitars because the model was discontinued.

“So he bought the box of pickups and then we started installing Firebird pickups [in the neck position of Teles]. But I didn’t like that, either, you know? So there was a lot of experimenting going on. But the typical experiment was to rout a big hole in a guitar and hope for the best.

“Actually, I don’t like Tele neck pickups at all – never did. As a matter of fact, when we [in later years] made the Twang King pickup, Steve Blucher was working on the design and I had just come back from Japan, where I was actually seeing an increase in interest in Telecasters.

“And we had a request from our distributor saying, ‘Well, why don’t you make a neck pickup?’ So Steve Blucher said to me, ‘What do you want the next pickup to sound like?’ And I said, ‘Like a Stratocaster!’ But what Steve did was actually better: the Twang King has what I would describe as that elusive, mythical sound that you think you should be getting.

“That said, I always thought the Stratocaster’s bridge pickup sounded terrible. Hence, the very first rewinds that I did were to change the sound of that bridge pickup to be warmer and darker – because what I really wanted to do was shift it in the direction of a P-90. I wanted that warmer, bigger, fuller [tone]. That was really the first pickup I designed from the ground up, where it was like, ‘I don’t want to fix the pickup, I want to change the pickup.’ Which is the separation between just repairing something and actual design.”

Back in those early days, you repaired an awful lot of pickups. What did you learn while fixing them that influenced your own pickup designs later on?

“One of my theories when I first started the company was that I never wanted a pickup back because it broke, right? So during the thinking and engineering process, I would kind of go a little bit more heavy duty than needed, simply because I would rather build in a safety factor.

“Even today, when we work with artists they might say to us, ‘We’re going out on the road – could you send me some guitar straps?’ And we’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, sure. We’ll send you out guitar straps. What do you need?’ And they might say, ‘Well, I need six.’

“To which we’ll reply, ‘Well, take nine,’ right? And we’ll ask them what pickups are in their guitars and what pots they’re currently using. Then we’ll send them all of that stuff. So my standing joke with roadies is, if you have just one of anything in the case [of equipment that we send out], it won’t break. So it’s about ‘How do we make this so it doesn’t need repair?’ I love things that don’t need repair.”

You’ve described how Gibson and Fender failed to grasp what players wanted from the guitars they made during the ’70s. In what sort of ways did factory pickups fitted to guitars during that period represent a backwards step, in your view?

“Well, I realised early on that original PAF pickups sounded significantly different to the early ’70s and late-’60s pickups that we were seeing. For example, one of the things that Gibson had decided to do was make the Alnico magnet shorter. And I’m going to say that was probably a bean-counter decision. Corporations have a tendency to allow the bean-counters to have a little bit too much freedom in my opinion.

“The story that I got – not verified – was that Gibson came out with a Melody Maker that had a bar magnet down the centre of the coil, and they wrapped the coil around that to make a cheap single coil that only used one magnet, okay? And the story that I got is that they decided to use the same Alnico magnet in [both the budget single coils and in standard humbuckers]. So in order to make that work, they shortened the magnet that was used in the regular humbucker.”

The DiMarzio Super Distortion was the first high-performance replacement humbucker to hit the market and it has been in demand ever since. What tonal benefits did it offer to guitarists as compared to factory humbuckers made by Gibson and others?

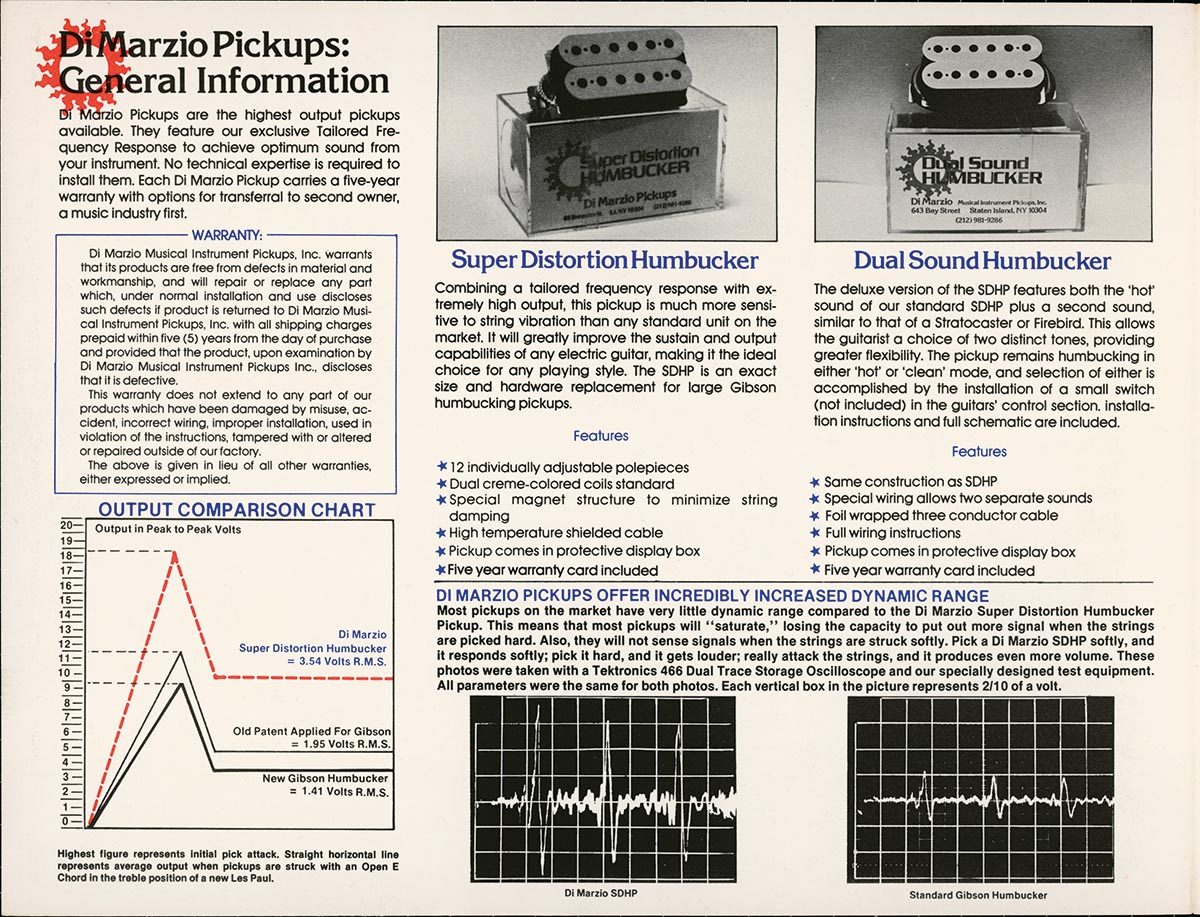

“Well, we made a device called a ‘Universal String Plucker’. It looked like something from a child’s Erector Set, but it had a guitar pick that swept across the strings and the idea was that the plucking was consistent, right? So we rigged a guitar so that it was being played [by the Universal String Plucker] and then used an oscilloscope and a camera to record the results.

“In essence, this showed how different pickups performed while being plucked with the same intensity. So you’ll see on those graphs that there is an initial peak, then there’s a high point and finally there’s the sustain.

“So using the Universal Plucker and striking all six strings, the Super Distortion produced 3.54 volts RMS, whereas an old ‘Patent Applied For’ produced 1.9 volts RMS and then the newer – at that point – 70s humbuckers produced 1.41 volts in our test results. So, again, part of my logic was: if we had a pickup with higher output, it would drive a Fender or Marshall amplifier into distortion.

“If you wanted to come out of distortion, you just rolled the volume back. And by clipping the front-end of the amp with the higher output of the pickup, the guitar now sustained longer, simply because you had more voltage hitting the front-end of the amplifier.

“I read an article recently [featuring a] Tony Bacon interview with Seth Lover, and Seth Lover talked about the original PAF pickup and how what they really wanted at Gibson was a kind of P-90 sound but quieter. And he came up with the idea of using the two coils to cancel most of the noise, put it in a metal cover, which again is all textbook.

“He talked very specifically about how the original pickup that he designed had a stainless-steel cover, but they had difficulty attaching that because he wanted to have what I would call an almost ‘magnetically invisible’ cover. Which didn’t happen. And then when you change the plating on the cover… the cover becomes slightly magnetic, which means that you are [leaching] the magnetism away from the strings and dissipating that in the cover, so to speak.

“All of us in the guitar business were taking the covers off pickups anyway. That was the other thing that I did all the time. And again, doing that allows you to raise the pickup up higher and closer to the strings. So all that was just a way of doing exactly what I eventually did [with the Super Distortion], which was to increase the initial output to the amplifier.”

When you made the first prototypes of the Super Distortion you used surplus components left over from Bill Lawrence’s shop. In your biographical essay The Birth Of The Super Distortion, you describe using nails to pack out the space between the improvised magnet you used and the prototype pickup’s other components. What effect did that have and how did it influence the onward development of the Super Distortion?

“Well, it changed the iron load of the actual pickup – because there was now more iron. When I was working for Bill Lawrence and he left the ’shop, there were scraps left laying around, including some ceramic magnets.

“The funny part is I took some of the ceramic magnets, which were not the right size, and installed them in a pickup and liked it better… because the other thing [besides increasing output] that I was doing was tone shaping. If you had a big, loud, bright pickup, I felt it was just annoying. What I really wanted was that singing, ‘vocal’ quality, especially in the bridge position, you know?

“So I built those first pickups with the magnet scraps using iron [to fill a gap]. Then, when I could afford it, I went and bought my own magnets and changed the dimensions of the magnet, then A/B’d the two – and realised I didn’t actually like the new, larger magnet! So once again it was like, ‘Oh, gee, if I put this in, it should work better.’ But, no, when I tried it, I didn’t like it.

“The same thing happened with amplifier work. I once built an ultra-linear Fender amplifier from a schematic, making what I thought were improvements to it – and it was a great PA amplifier but an absolutely horrific guitar amplifier. It would not break up.”

Great guitar tone often comes from things not working with ‘perfect efficiency’. But perfect efficiency is at least a clear goal. So how do you identify the elusive design elements that make a pickup or guitar amp sound good to our ears?

“Well, trial and error, error, error – over and over. You keep making mistakes and that kind of teaches you not to do certain things.”

That was one of the early goals: clearly establishing the fact that I’d done something very different from what Gibson was doing

The Super Distortion was the first aftermarket pickup of its kind, so how did you get people to take notice of it?

“I used to go around to music stores with my Goldtop Les Paul [fitted with a Super Distortion at the bridge] and I would say to them, ‘The neck pickup is always louder, right?’ And the store owner would agree. So then I plugged the guitar in, played the neck pickup then switched to the bridge pickup – which was, of course, louder with a Super Distortion – and I’d say, ‘Not any more.’ And that would sell six pickups… [laughs].

“But that was one of the early goals: clearly establishing the fact that I’d done something very different from what Gibson was doing. And when I finally got [a really good, genuine] 1959 Les Paul, it was magnificent… But if I was going to play a gig, I would have taken a guitar that I’d built that had a Super Distortion in the bridge position. It really let me do whatever I wanted to do and you got a very different effect to what a stock Les Paul would give you.”

Looking back over the decades since the Super Distortion’s launch, how gracefully do you think it has aged as a design? Is it still relevant today, when hundreds – possibly thousands – of hot humbuckers are now available to players?

“Oh, gosh… Oddly enough since we’ve written The Birth Of The Super Distortion article, I’ve had lots of love mail about how many people got it, love it and still use it and it’s their favourite pickup. I’m really proud of the design because it was groundbreaking – still is in many ways – and it’s really the pickup that everyone targets: you have guys on YouTube going, ‘Well, we compared the Super Distortion to this, this and this…’

“And you have to realise that basically anyone that’s building that kind of product is basing their design work on what I did 50 years ago… In a funny way, it’s the ‘SM57’ of the guitar pickup business. It’s got a shit-ton of hits [to its credit]. And it has its own character.

“As a matter of fact, the guitar player who’s out with Corey Taylor [Christian Martucci] is a big Super Distortion fan. And when we first met, he just sang the praises of how much he liked recording with that pickup because it just works. I’m like, ‘Do you want to try this? Or do you want to try that?’ And he’s like, ‘No, in the bridge position, I really like what this does.’

“He’s now recorded an album with a bunch of different things. But in particular, he’s playing a Phantom in the bridge position – which is a modification on a P-90 we’ve made – but so many of the other recordings that he’s doing are all Gibson guitars with Super Distortions in the bridge. So the takeaway, for me, is that it’s a good piece of work. It’s consistent. I never sold it out. It’s never been built in Asia. And the goal was always to keep the brand and the identity clean.”

How important has practical input from artists been in shaping what DiMarzio pickups are today?

“You can come up with ideas that you think are good in your design area… and then you still have to take them into the marketplace. I mean, a lot of the pickups were road-tested, not just by me but by my friends. I mean, imagine if you would, it’s 1973, KISS is formed and recording, but they’re not even out on the road yet.

“Right? Ace Frehley and I meet up and I give him some pickups because he heard about them. Well, those pickups were out on the road for like a year. Now, if there were problems, I was going to hear about it.

I like the idea of getting a product and road-testing it. Corey Taylor’s doing worldwide probably for a year, and our Phantom pickups will be out on the road doing a lot of shows

“Another example: Yngwie Malmsteen used the HS-3 pickup because basically he wanted an FS-1 that was quiet. The first version of the FS-1 [we came up with] that was quiet was an HS-3. After going through HS-1 and -2, that was the third version. He road-tested that pickup for about a year, liked it and that was that and he used [it for some time]. So I like the idea of getting a product and road-testing it.

“Corey Taylor’s doing worldwide probably for a year, and our Phantom pickups will be out on the road doing a lot of shows. Something either works or it doesn’t [in that demanding environment], and the last thing I want to hear is, ‘Oh, gee, we had to fix this in the mix.’ It should be: plug it in, it sounds right.”

- Visit DiMarzio to read more about the birth of the Super Distortion.