In February 1979, Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow gathered together at Chateau Pelly de Cornfeld, a 13th-century castle in the foothills of the French Alps. Picture-postcard Geneva was a short drive over the border, the snow-capped Alps ranged across the horizon. It was to this storied, idyllic spot that the band had come to make their fourth album.

Down To Earth would end up being a very different-sounding record to its three predecessors. But then this version of the band was nothing like even the one that had made Rainbow’s previous album, Long Live Rock ’N’ Roll less than two years previously. Apart from Blackmore, drummer Cozy Powell was the sole survivor of those sessions.

They were joined by new keyboard player Don Airey, and were without a singer and bassist, although their producer, Blackmore’s erstwhile Deep Purple bandmate Roger Glover, was brought in to fill in the latter role.

This, though, was entirely typical of how Blackmore conducted his business, which is to say eccentrically, wilfully and with serial eruptions.

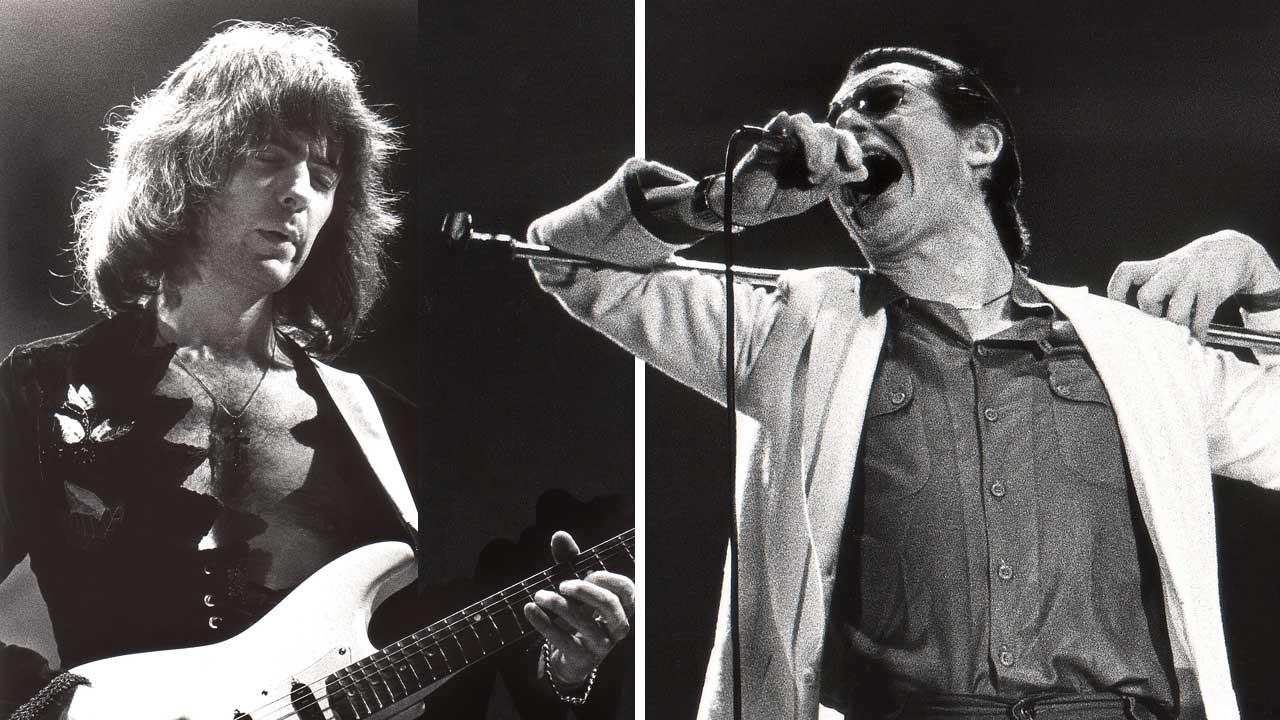

Mercurial as a guitarist, faintly menacing as a character, Blackmore had started Rainbow in 1975. Initially it was as an adjunct to Purple, when his fellow members of that band had sniffed at a new song that he’d come up with, a strident, virtuoso hard rocker that was to be titled Sixteenth Century Greensleeves. Using one of Purple’s American support bands, Elf, and notably their singer, Ronnie James Dio, Blackmore had ostensibly recorded a solo album.

Alongside the quarrelsome Greensleeves, Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow was chockfull of other strident, virtuoso hard rockers. Blackmore liked it well enough to bail from the then-ailing Purple and set about establishing Rainbow in its own right. A second Rainbow album, the titanic Rising, was recorded within 10 months. By then Blackmore had jettisoned all of the Elf contingent except Dio. In had come drummer Powell, late of the Jeff Beck Group, bassist Jimmy Bain and American keyboard player Tony Carey. But Dio was Blackmore’s most potent weapon.

Bain and Carey lasted one tour. In their place Blackmore brought in Australian Bob Daisley on bass and Canadian David Stone on keyboards. It was this latest new line-up that made Long Live Rock ’N’ Roll. Three quarters of that album was peerless hard rock, taut, muscular and melodically vivid. But during the recording and touring of it, cracks began to open up in Blackmore’s relationship with Dio. In part, Blackmore blamed Dio’s soon-to-be-wife Wendy for forcing the two of them apart. “She was nice enough,” he considered, “but we didn’t really click.”

“I always found Ritchie to be a very aware person, intelligent, but he could be a bit quirky and he didn’t suffer fools gladly or easily,” says Daisley. “I came to terms with the fact that it was Ritchie’s band, but I think Ronnie, more than anyone, had a problem with that fact.

“On stage there were a couple of songs on which Ritchie and Ronnie would improvise. Ritchie would play whatever he fancied and Ronnie would sing along to it. There were a couple of nights on the tour that Ritchie made that spot very difficult for Ronnie. Afterwards, Ronnie would be a bit paranoid. He’d come off stage and be like: ‘Oh, fuck, am I gone next?’.”

For all that Daisley kept his head down, he was gone, and so too was Stone when in October 1978 Blackmore initiated rehearsals for the band’s next album. Powell and Dio were retained, and Glover was producing. Glover’s appearance on the scene was surprising. Five years earlier, Blackmore had engineered his ousting from Purple. Glover had progressed to making a career for himself as a producer, having in the interim worked with Scots rockers Nazareth and also Elf, and clearly had not carried a grudge.

“Why should I have done? I’m a huge Ritchie fan,” he says. “When he asked me to produce Rainbow I thought: ‘Why not?’ He was playing brilliantly and it was a good opportunity for me.”

However, the work that was managed over the first week of rehearsals in Connecticut was hard labour and yielded scant results. Blackmore and Dio were utterly at odds with each other. The problem now was that Blackmore was fixed on steering Rainbow towards a more commercial direction. In America in particular, they had not got close to measuring up to Purple’s stature. Rankled, Blackmore wanted to hear his band being played on the radio, for them to have hit singles.

Dio, meanwhile, wasn’t in the least interested. One day after the next, Blackmore would start to play a piece, Powell would follow his lead, while Dio sat in a corner, scribbling away in a notebook or staring off into space. Rare were the occasions that Dio stood up to sing, and when he did it amounted to not much more than bored, listless mumblings.

“I soon became aware of the frosty relationship between the two of them,” says Glover. “There was a huge gulf between them over what they wanted."

Inevitably, it was Blackmore who prevailed. As Glover puts it: “After that week, things exploded and Bruce Payne, who managed both Rainbow and me, came and told me that Ronnie had quit.”

Blackmore, Powell and Glover pressed on. They brought in former Colosseum II keyboard player Don Airey, but they arrived in France for a scheduled six weeks of sessions depleted and without any new songs. After trying out a couple of bassists, Glover took on the role. Soon, Glover also took over the slot Dio had vacated as Blackmore’s co-writer.

In short order, Blackmore and Glover pulled together enough songs for an album. Of these, only Eyes Of The World harked back at all to the fantastical stylings of the Dio era just past. The rest were punchier, more streamlined, and radio-friendly as Blackmore had intended. And where Dio’s lyrics had evoked images of mystical worlds populated by wizards and dragons, Glover’s concerns, as set out on All Night Long, Makin’ Love and Lost In Hollywood, were decidedly more earth-bound.

The song that was to epitomise Rainbow’s volte-face, though, was not one of Blackmore’s and Glover’s, but a cover. A snappy, keening slice of straight-up pop-rock, Since You Been Gone had been written by former Argent guitarist/vocalist Russ Ballard for his 1975 solo album Winning. Bruce Payne had brought the song to the attention of Blackmore, suggesting it might be just the type of crossover song he craved.

“Bruce informed me one day in the office that Ritchie wanted to do Since You Been Gone, and I said ‘Never’,” reveals Glover. “It was a pop song. And at that point the last thing I’d heard from Ritchie was Stargazer, which I considered to be a masterpiece.”

Glover wasn’t the only one incredulous at Blackmore’s acquiescence. He, at least, though, appreciated Blackmore’s motives. Powell, a staunch traditionalist, loathed Ballard’s song. When the four of them started putting down backing tracks – having set up in the castle’s cavernous dining room, with a mobile studio parked outside, the leads passed through the open windows – Powell refused point-blank to drum on Since You Been Gone.

There was still the pressing matter of finding a new singer. According to Glover, several candidates were whisked out to the chateau, but none met Blackmore’s precise specifications. Blackmore wanted someone who sang with the soul and grit of Paul Rodgers, and who had the vaulting range of Lou Gramm of Foreigner.

One night, Blackmore, Powell, Glover and Airey fell into a game of Name That Tune, with the drummer picking selections from his collection of 60s tapes. A track called Only One Woman, by British duo Marbles, written by the Bee Gees and a Top-Five hit in the UK in 1968, caught Blackmore’s ear – specifically, its powerhouse lead vocal did.

Skegness-born Graham Bonnet had formed Marbles with his cousin, Trevor Gordon. When their brief flush of fame had passed, Bonnet had kept his hand in singing jingles for TV adverts. In 1977 he had made a solo album. It went unnoticed in Britain, but gave him another Top-Five hit in Australia, with a cover of Bob Dylan’s It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue. The next year he had an Australian No.1 with another Bee Gees song, Warm Ride, which well utilised his four-octave range.

Glover happened to know of a fellow producer who had recorded a recent session with Bonnet. Through this contact, Blackmore arranged to have Bonnet flown out to France to audition.

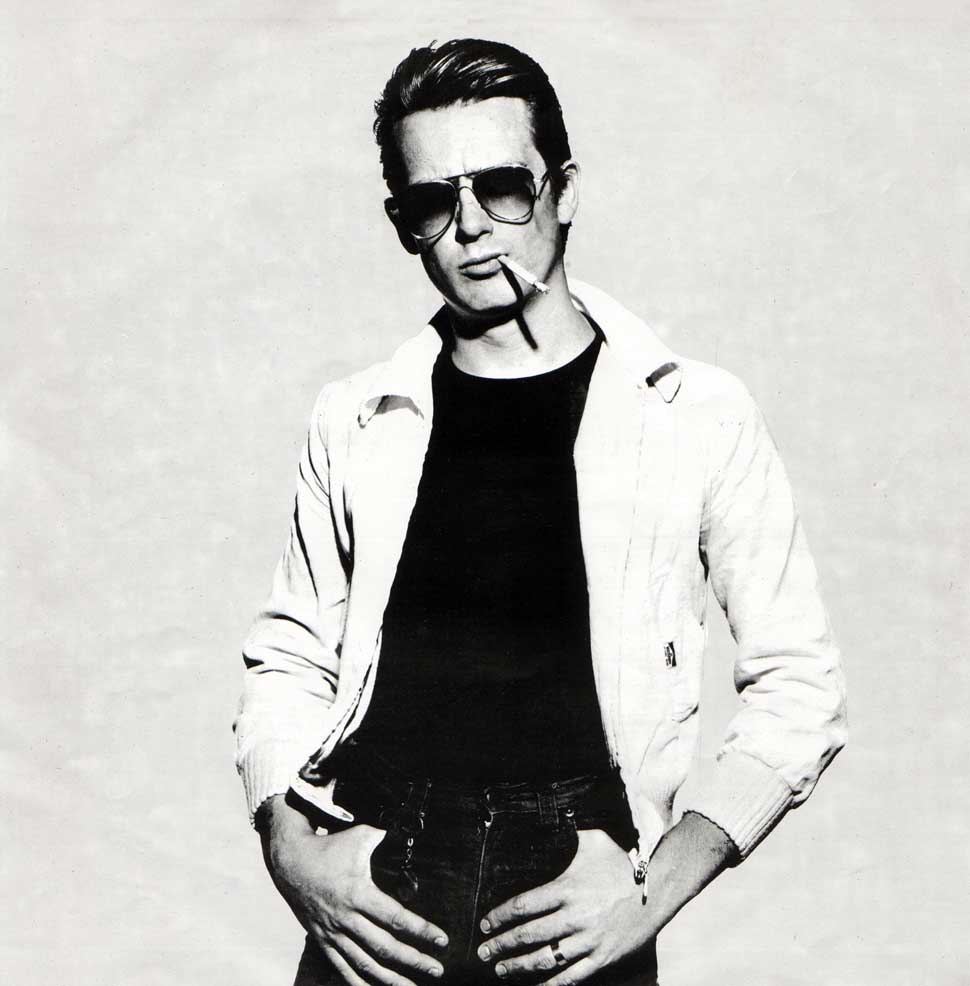

For his part, the 31-one-year-old Bonnet saw himself as an R&B singer. He had a sketchy appreciation of hard rock, and none at all of Rainbow. By chance, around that same time he had turned down an offer to join the Sweet as replacement for Brian Connolly, believing he was ill-suited to the job. Rainbow threatened to propel Bonnet even further out of his comfort zone. This was further enforced when Bonnet pitched up at Chateau Pelly de Cornfeld, sporting a suit and tie, his hair cut short and slicked back, looking like no one so much as a well-scrubbed James Dean.

“I’d had to go out and get Rainbow’s albums and listen to Ronnie’s stuff,” says Bonnet. “Even then, I’d thought: ‘This isn’t me.’ They had asked me to learn [Purple’s] Mistreated for the audition. I sang it in front of the four of them, off microphone, because I thought I was bound to screw up.”

In fact, Bonnet bowled them over.

“My impression was the same as everyone else in the band – the greatest singer any of us had ever heard,” says Airey.

“They were all smiling away by the time I finished,” Bonnet continues, “and they offered me the job on the spot. I had to say that I didn’t know. I didn’t look like them and I wasn’t into their music. It was very confusing, totally alien to me. So I flew back to London to think it over.”

Within days, Bonnet had decided to throw in his lot with Rainbow and returned to France.

Seven of the album’s eight songs just required him to get his vocals down, but this proved a painstaking and fractious process. According to Bonnet, with Glover looking on he was required to sing each song four different ways. Glover “would give me a vague idea of melody and then tell me to do whatever I wanted to make the song my own”.

It still gnaws away at Bonnet that he was not subsequently assigned any songwriting credits on the Down To Earth album. “They knew I was the new boy and they pulled the wool over my eyes a little bit,” he claims. “Yes, Roger did the lyrics, but the melodies were mine. I was very green. It wasn’t until years later that I thought: ‘Wait a minute, I wrote those songs!’

“It was exhausting, too. We had four different kinds of choruses for every damn song. Then Ritchie would come in and pick which he thought was the better way to go.”

Blackmore’s looming presence was otherwise felt with his penchant for practical jokes. Having made sure to spook the others about the castle’s haunted history, he took to tying lengths of string to their bedroom windows and so that he could cause them to fling open in the dead of night.

To Bonnet, though, Blackmore’s reputation as “someone who was dark, miserable and wants to kill people” seemed just then to be wholly unwarranted. “He wanted me to be comfortable and settle into the band, and he was very friendly towards me and on my side,” he recalls. “From all the stories that I’d heard about him, that he was horrible and whatever, I couldn’t quite believe it. I found him to be very shy but a good guy."

After a couple of weeks, Bonnet also concluded that the chateau’s grand dining room, with its high ceilings and stone walls, was “horrible for vocals”.

Operations were therefore moved to a more conventional studio on the US East Coast, Kingdom Sound on Long Island, where Bonnet finished off his vocals. When they left France, Glover had at last coerced Powell into playing on Since You Been Gone.

“I told him he had no choice, that he had to play it,” says Glover. “So, with me playing a guide rhythm guitar, we had managed to record just the drum track. Cozy expressed his feelings about it by playing something overly simple. When we got to Kingdom Sound, we added all the other instruments, along with stacked vocals and plenty of percussion and, strangely enough, Cozy’s bareboned performance worked in the song’s favour.”

Down To Earth was released that July, to mostly lukewarm critical notices. In a three-star review in Sounds, Geoff Barton lamented: “I feel myself pining for the days of yore, when even the band’s more basic tracks had an epic feel.” In particular, Barton took aim at Since You Been Gone. “I can’t imagine Blackmore stooping so low as to play this live. It really is the pits,’’ he wrote.

Not that Blackmore was unduly troubled. Down To Earth fast became Rainbow’s best-selling album, hastened along by Since You Been Gone becoming a Top 10 hit in the UK. A second single, All Night Long, charted even higher than.

It also drew stinging criticism on account of Glover’s lyrics – most infamously, the verse: ‘You’re sorta young, but you’re overage, I don’t care, cos I like your style/Don’t know about your brain, but you look alright.’ Although a bullish Blackmore, feeling vindicated, brushed off being labelled a “sexist pig”, telling Sounds: “Everybody knows that it’s all tongue-in-cheek, and anybody who doesn’t know that isn’t worth being talked about anyway.”

Speaking to Sounds that same year, Dio volunteered another perspective: “No matter what he does, Ritchie always comes out alright. If he fell into a vat of shit he’d turn out to be wearing a rubber suit.”

The tour to promote Down To Earth began in Lakeland, Florida on September 2, 1979, and with Glover persuaded to join the band on bass full-time. Rainbow spent the next three months criss-crossing North America, coast to coast, playing a total of 57 headline dates in arenas and auditoriums.

As it happened, Blackmore had no qualms about performing Since You Been Gone live, and in general the band’s sets leaned heavily on the new album. Man On The Silver Mountain, Catch The Rainbow and Stargazer were among a smattering of Dio-era songs included in the set.

“There were also a couple of instrumentals that they did without me,” says Bonnet. “It was kind of an easy gig. I would have time to relax backstage and have a drink, and do whatever else was done at that time. I probably enjoyed it too much. It was the usual stuff that you hear from every band. There was always loads of booze in the dressing room, along with a lot of girls. But every night, I remember going on stage with that band and feeling totally comfortable, that nothing would ever go wrong. It was like walking into a warm living room with a blazing fire.”

Still, the atmosphere was not as tolerant as it had been at Chateau Pelly de Cornfeld. Bonnet’s odd-man-out appearance had started to get under Blackmore’s skin, and likewise the quirks of his personality. Bonnet’s preferred on-stage attire was tailored jackets, Hawaiian shirts and aviator sunglasses. As the tour wound on, he grew accustomed to these items vanishing from his dressing room. On more than one occasion, he discovered the trunk containing his wardrobe to be locked and the key spirited away.

“Ritchie just didn’t like the way that I looked, so he would toss my stuff out,” he says. “The problem for Ritchie was that I wasn’t into the uniform – Spandex pants and Cuban-heel boots. That whole thing did get a bit nasty.”

“Fucking hell, Graham,” Blackmore once reflected to Classic Rock. “He was a nice enough guy, but just completely… lost. One day I said to him: ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘Oh, not too good,’ he replied. ‘I feel kind of funny.’ Someone else said: ‘Have you eaten?’ ‘That’s it – I’m fucking hungry!’ He had literally forgotten to eat for ages. And all these singers used to say I was a mental case.”

Whatever ties had bound Bonnet and Blackmore together were snapped when the tour arrived in the UK in February the year following. Ludicrously, the catalyst was a haircut. The scene was the Ingliston Exhibition Hall in Edinburgh, the third date of the British run, on February 22. Fearing that Bonnet was scheming to have a haircut, Blackmore posted a guard on the singer’s dressing room door to prevent him from leaving the venue. Bonnet, though, snuck out of a window, high-tailed it to a barber’s and got himself a severe crop.

“I didn’t see Ritchie, or anyone else, until I went on stage that night,” Bonnet recalls. “Ritchie came on, clocked my haircut and gasped. He walked straight back off, and ended up playing the entire gig from behind his amplifiers.”

“We were a long-haired band,” Blackmore protested to the Guardian in 2017. “In 1979, everybody wore denim and had straggly hair. But Graham looked like a Las Vegas casino man. It was very petty, but it had become an obsession with me. He was threatening to have his hair cut just to annoy me. It’s the principle. I took it as an insult. I don’t think I spoke to him again after that."

Cozy Powell, too, had reached the end of his tether, but that was because of having to play Since You Been Gone every night now. He got an offer to join the fledgling Michael Schenker Group, and for better money, and informed his bandmates that he would be leaving them at the end of the tour.

It was in this conflicted state that Rainbow descended upon the English East Midlands for the tour’s last hurrah. They were to headline the inaugural Monsters Of Rock festival, at the Castle Donington racetrack, on August 16, 1980. There, in front of a crown of 60,000, coming on stage after Touch, April Wine, Riot, Saxon, Scorpions and Judas Priest, Rainbow Mk IV turned in their valedictory performance. It was a toothless, lacklustre show, encapsulated by Bonnet forgetting the words to Stargazer.

“We weren’t at our best that night,” Bonnet admits. “It was disappointing because we were losing Cozy and we were tired. The organisers had expected a small crowd, but it ended up being fucking huge, so it still was the most incredible night that I’ve ever had.”

Two months after Donington, Rainbow regrouped once more at Sweet Silence Studios in Copenhagen to ready their follow-up to Down To Earth. The drummer that Blackmore had found to replace Powell, a Long Islander called Bobby Rondinelli, didn’t have a track record outside of playing in bar bands. Blackmore had also brought along with him another Russ Ballard song, I Surrender. Bonnet laid down a guide vocal for that track, but the sessions ground to a halt after just a week.

“Ritchie pretty much stopped coming into the studio,” says Bonnet. “No other songs had been written, so the rest of us didn’t have anything to do, and with the new drummer the buddy system had broken down. Once in a while Ritchie would drop by and ask us how it was going. He might pick up his guitar and play a chord, but that would be it. It was all very strange. And boring.

“Don Airey said to me that he was going home and leaving the band. So I said that I was going to go, too. I went home to LA, and Don stayed. They asked me to come back, but I didn’t want to. I fired from myself Rainbow on the phone. I really thought the band had come to an end. But looking back, I should have stuck it out. I mean, even my mum and dad asked me what the hell I thought I was doing.”

Bonnet went on to record a second solo album, Line Up, which Powell played on and which spawned a Top 10 UK hit, Night Games. He then had what would be his combustible, even shorter-lived tenure in the Michael Schenker Group.

To replace Bonnet in Rainbow, Blackmore chose an American singer, Joe Lynn Turner, and the band knuckled down to make what would become the so-so Difficult To Cure album. There followed two more records made with Turner, and various drummers and keyboard players, each as slickly polished and forgettable as the other.

In the range between Rising and Kill The King, track five of eight on Long Live Rock ’N’ Roll, Rainbow could justifiably lay claim to have been the greatest hard rock band of them all. Forty years on, their might, awesome and wondrous to behold, still pulses and flickers through Down To Earth which, Glover rightly suggests “still sounds fresh and powerful”. But then it was gone, blown out like a summer storm.

Perhaps it’s Don Airey, who did in the end quit Rainbow, “devastated” after the tour for Difficult To Cure, who best ascribes reason to their tortured sage. “Those initial few weeks in a rehearsal room with Ritchie had a profound influence on me that lasts to this day,” he says. “The sound of his guitar was an amazing thing to experience first-hand, so to speak.” A

And yet, reflecting upon his rejoining Blackmore, and also Glover, in the rebooted Deep Purple in 2001, Airey noted that he “was kind of braced for all the old bollocks, which is to say the moods, and people being late and playing badly on purpose, and being rude to everyone”