Most people — art lovers or not — have heard of Pablo Picasso, one of the art world’s biggest historical superstars. But they might not know the extraordinary breadth of his work or understand why he is seen as one of the most pivotal artists of the 20th century.

That’s where a new exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago comes in. Titled “Picasso: Drawing from Life,” it runs Saturday through April 8, 2024, and includes more than 60 works dating from 1899 through 1969.

This Picasso offering is the first at the Art Institute since “Picasso and Chicago,” a sprawling exhibition in 2013 that marked the 100th anniversary of the museum’s first presentation of the Spanish artist’s works as part of the touring Armory Show — a landmark, revelatory look at the avant garde.

This latest smaller-scale exhibition is a handsome showcase of the Art Institute’s collection of Picasso drawings (about half of the museum’s works by the famed artist in that medium are on view) and original prints — one of the best such holdings in the country.

“While we don’t have the bulk, the numbers that [New York’s] Museum of Modern Art does, what we have is really good — so all the periods of Picasso’s career highlighted with really good examples of that moment,” said Emily Ziemba, director of curatorial administration and research curator, prints and drawings. She organized this exhibition along with Jay A. Clarke, Rothman Family Curator, prints and drawings.

There is nothing especially new or groundbreaking about this show, and it is not meant to be. Instead, it offers a compact yet impressively thorough overview of the main phases of the Spanish artist’s career, one that should appeal to those familiar or unfamiliar with his work.

The show coincides with the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death, but the main catalyst for this undertaking was the museum’s most recent acquisition created by the artist — a 2020 partial and promised gift from Susan Manilow in memory of her husband, Lew Manilow, a life trustee of the Art Institute who died in 2017.

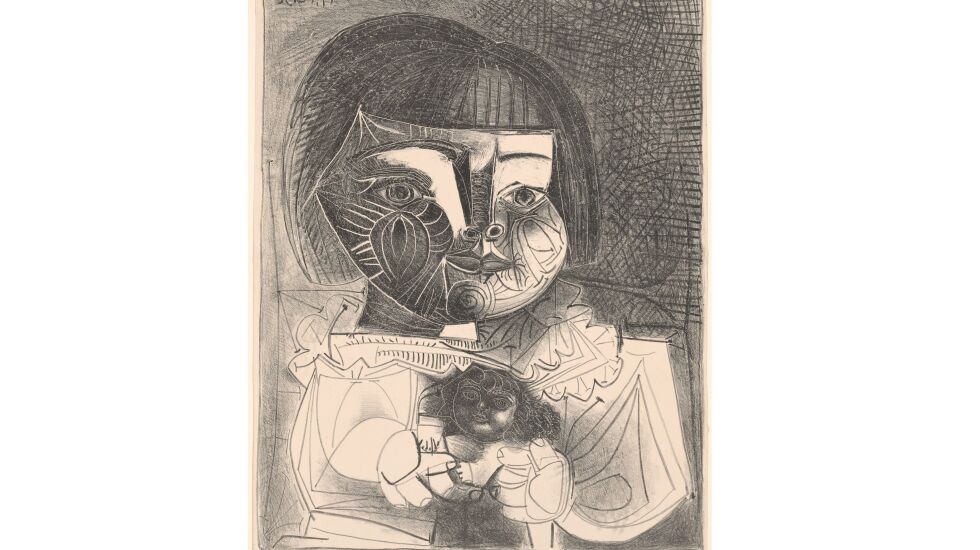

This simple but arresting drawing, titled “Head of a Woman with a Chignon (Fernande)” (summer 1906), is part of a striking group of four works depicting Fernande Olivier, who was Picasso’s partner and frequent model for eight years.

As an added dimension, this exhibition highlights some of the collaborators who were important in Picasso’s life, including art dealers Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and his wives and lovers like Olivier, Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar.

Also highlighted is Georges Braque, a fellow artist with whom Picasso developed cubism around 1907-08, a revolutionary way of fracturing reality and presenting subject matter from multiple perspectives simultaneously.

Braque is represented by “Bal (recto); Guitar (verso)” (1912), an early example of collage, with several attached squares of simulated woodgrain wallpaper — the only piece in the show that is not by Picasso.

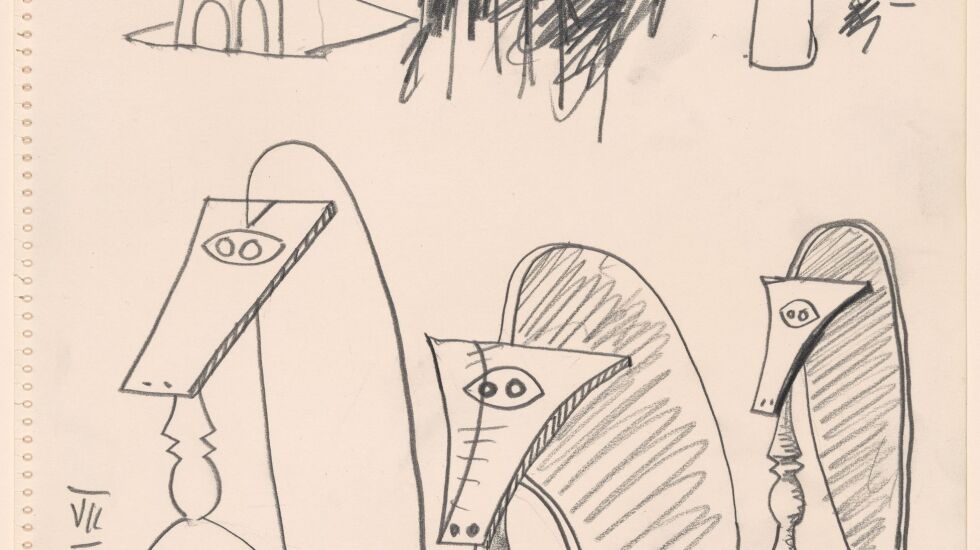

Among the show’s other drawings is “Six Busts of Women” (May 21, 1962), a group of studies that has special relevance for Chicagoans. They relate to the 50-foot-tall untitled sculpture that Picasso designed for Daley Plaza — a 1967 work that has gone on to become an internationally known Windy City icon.

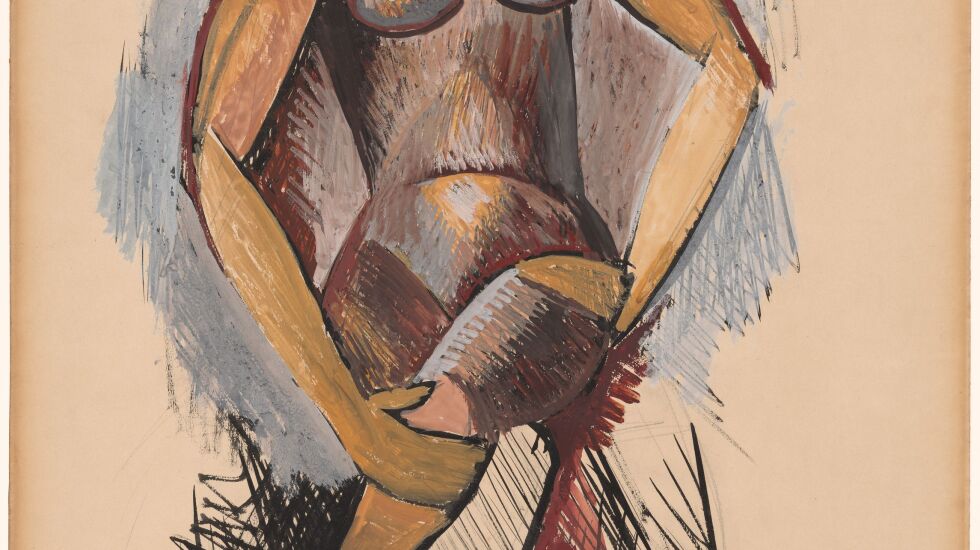

“There is also Seated Female Nude,” (summer 1909), a watercolor and gouache over graphite on tan woven paper. There are no studies in this show for Picasso’s breakthrough 1907 painting, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” but the mask-like face and faceted depiction of the figure in this 25¼-inch-tall drawing two years later certainly echo that celebrated work.

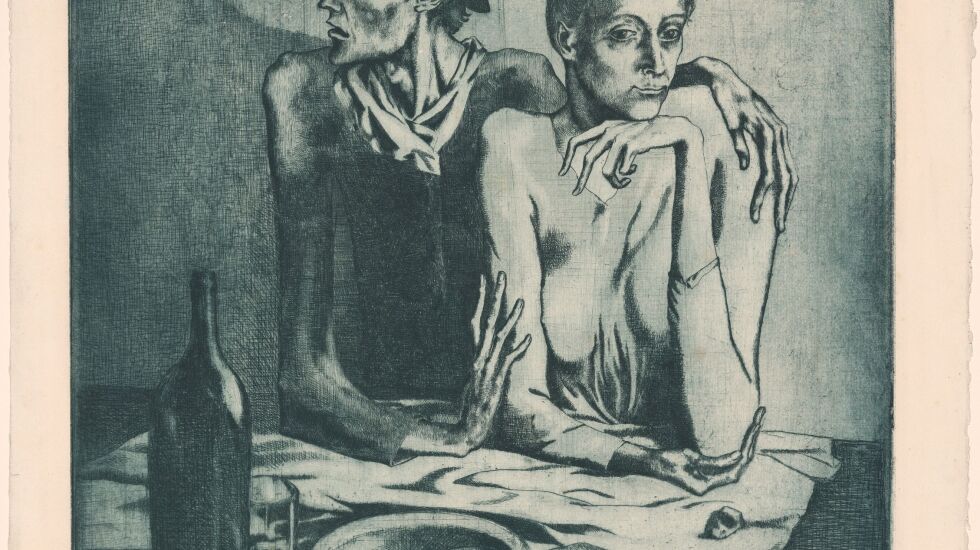

Picasso demonstrated amazing facility for virtually every medium he took on. That is especially true of printmaking, where he excelled at multiple techniques, as many striking examples here make clear.

One of his most famous is “The Frugal Meal, from “The Saltimbanques,” (September 1904), a moving etching from Picasso’s melancholic Blue Period that was just his second attempt at printmaking. It depicts two forlorn, emaciated figures at table.

Other notable examples include “Minotauromachia” (March 23–May 3, 1935), a 27¼-inch-wide etching that is a technical tour de force, as well as five examples of his bold linocuts, a technique that the artist experimented with from 1962-67 alongside printer Hidalgo Arnéra. Among them is the reddish-brown “Still-Life with Lunch I” (1962).

The show also includes one sculpture, an illustrated book and three paintings. These works are meant to supplement the predominant works on paper and fill in gaps in the chronological and stylistic narrative of Picasso’s career.

Deserving special note among the three paintings is “Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler” (autumn 1910), a 39½-by-28½-inch abstracted portrait that the two curators called one of the most important cubist works in the world — a claim that is in no way hyperbole.

Although this work is usually on display as part of the museum’s permanent collection, it is rewarding to see it in the immediate context of other cubist works and the broader spotlight on the artist that this show provides.