If Prime Minister Anthony Albanese really wants to boost wage growth, there’s a simple way to do it.

And if he did that one simple thing, analysis prepared for The Conversation shows some of our most trusted but least well-paid workers – teachers and nurses – could be among the wage winners.

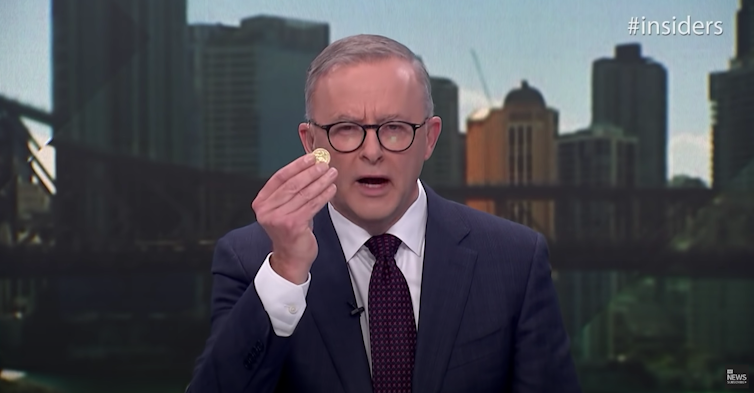

During the election campaign, the Labor leader made a public push for wages growth. He held aloft a $1 coin and said that’s what his government would be asking for: a boost in the minimum wage from $20.33 an hour to $21.36, which would lift it 5.1%, which was the inflation rate at the time.

After the election that’s what the government asked for. The Fair Work Commission delivered slightly more for Australia’s lowest-paid – an increase of 5.2% – and somewhat less for higher earners: an increase of 4.6%.

Then the inflation rate climbed to 6.1%. That figure, for the year to June, far eclipsed total wage growth of 2.6% over the same period and rendered even what the commission had delivered out of date, sending real (inflation adjusted) wages backwards by the most in 25 years.

Next week’s Jobs Summit is, in part, an attempt to do something about wages. But the issues paper released ahead of the summit is curiously bereft of ideas about how.

The paper says wages have traditionally climbed with labour productivity (which is output per hour worked) and that productivity growth has fallen to its lowest in 50 years.

It says if businesses invested more in labour-saving technology and workers got a better mix of skills, productivity growth would climb, but (and it’s a big but) that growth would only flow through to wages “over the medium term”.

Which leaves… not much happening for wages in the meantime.

Silent on what the states should do

The other things the paper notes are that fewer workers are covered by enterprise agreements and more by Fair Work Commission awards (presumably because enterprise agreements have expired, or aren’t high enough) and that 23% of workers are casuals (a figure that hasn’t changed much in 20 years).

What the summit paper doesn’t mention, but ought to, is that governments set wages – the wages of their own employees.

The lowest-paid quarter of the workforce has its wages set by the Fair Work Commission, either via the minimum wage or awards.

The Fair Work Commission looks after these people by usually increasing their wages in line with the consumer price index, and often by more.

Private employers are offering more, where they can

Most of the rest of the workforce gets only what their employers agree to, and the good news here is that, increasingly, employers are offering more.

Two years ago, as COVID took hold, the private employers who did lift wages offered an average of 0.8%. One year later, in the year to June 2021, they offered 2.7%. In the year to June this year they offered 3.8%.

Of course many private employers can’t offer much. They are small, and are being squeezed by soaring costs.

Read more: Are real wages falling? Here's the evidence

But governments budget in billions, and can afford to offer whatever they think they should, covering it with tax or borrowing.

The Commonwealth government, under Albanese, employs one quarter of a million Australians. The states, with whom Albanese could have a word, employ 1.6 million – many of them teachers and nurses.

Yet far from increasing their wages in line with inflation, or even in line with private sector increases, Australia’s states have been extraordinarily stingy.

Governments are offering as little as 1.5%

Victoria’s wages policy, announced in January, is for a cap on annual increases of 1.5%. Western Australia, despite its large budget surplus, is limiting increases to 2.5%.

NSW has a ceiling of 3%, which falls back to 2.5% after two years. (And the NSW ceiling is lower than it seems. It includes employers’ super contributions, which are to climb by 0.5 percentage points a year for the next few years, making the quoted ceiling of 3% a ceiling of 2.5% for take-home pay.)

Using Bureau of Statistics figures to examine the increases actually paid (as opposed to offered) shows Western Australian public sector wages climbed just 1.1% in the year to June. South Australian public sector wages climbed 1.7%.

In Victoria and NSW, the increases were 2% and 2.1%. Only Queensland, which shelled out 4%, paid anything approaching the rate of inflation.

Nurses and teachers hit hard

This stinginess hits most the two biggest groups of state government employees: teachers and nurses.

Whereas public wages as a whole climbed 2.4% over the past year, the wages of public education and training workers climbed 2.2%.

A Bureau of Statistics breakdown prepared for The Conversation shows that in NSW and Victoria those workers (mainly teachers) got just 2%. In Victoria, health care and social assistance workers (largely nurses) got 1.7%.

Economic research suggests the states are stingy, in part because they can be. They are the only big employer of nurses, teachers, police and public servants.

The PM could have a word

If Albanese means what he says about wages keeping pace with inflation, his next step should be to ask his mates in the states to do more. Most of the premiers are from his side of politics. All of them will be at the Jobs Summit.

There are signs he is putting his own house in order. His departments have been told not to enter into new agreements while the previous penny-pinching wages policy is under review, and he has backed a big rise for aged care workers (whose wages the Commonwealth funds) in a submission to the Fair Work Commission.

But going easy on the states, as he has so far, while telling private sector employers with far smaller financial resources) to lift wages, makes it look as if he is not serious.

If he genuinely believes wages ought to keep pace with inflation, he ought to name and shame his Labor mates.

Read more: The Chalmers graphs: 7.75% inflation, plunging real wages, weak growth

Peter Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.