One argument put forward in defence of fossil fuels is that they were a historical necessity, because there was no other viable substitute for much of the 20th century. We owe fossil fuels a debt of gratitude, the argument goes, because they supercharged our development. But what if I told you there was a viable alternative, and that it may have been sabotaged by fossil fuel interests from its very inception?

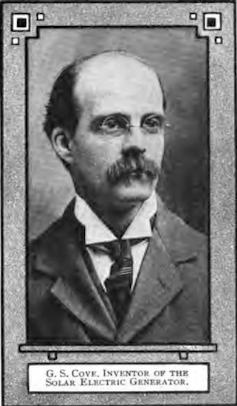

While researching the economics of clean energy innovation, I came across a little-known story: that of Canadian inventor George Cove, one of the world’s first renewable energy entrepreneurs. Cove invented household solar panels that looked uncannily similar to the ones being installed in homes today – they even had a rudimentary battery to keep power running when the Sun wasn’t shining. Except this wasn’t in the 1970s. Or even the 1950s. This was in 1905.

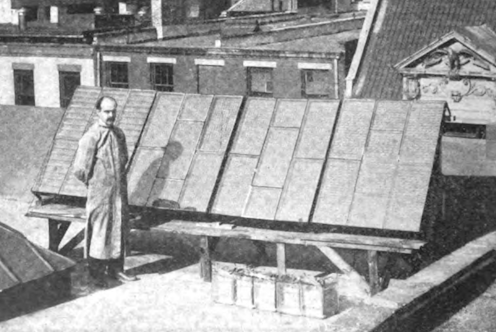

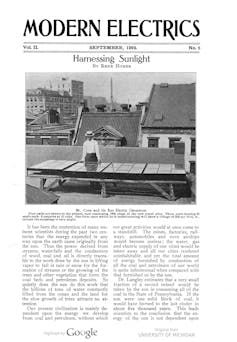

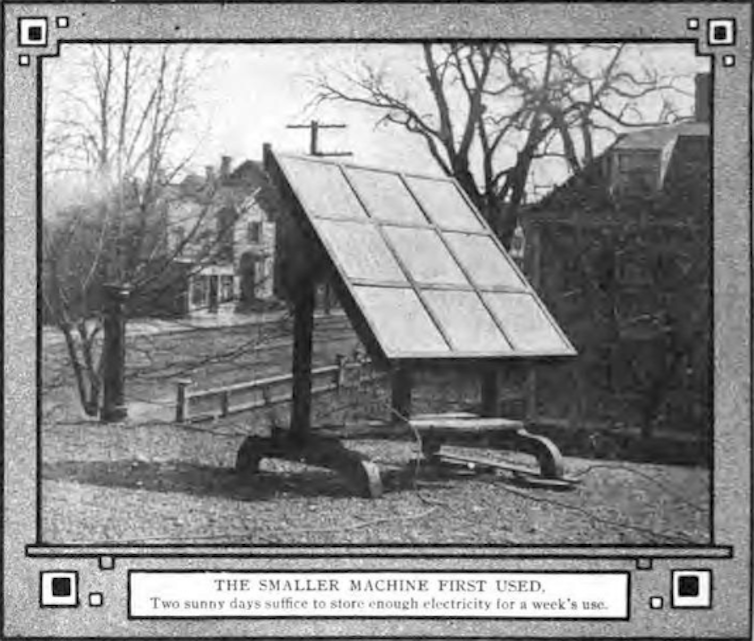

Cove’s company, Sun Electric Generator Corporation, based in New York, was capitalised at US$5 million (around US$160 million in today’s money). By 1909, the idea had gained widespread media attention. Modern Electric magazine highlighted how “given two days’ sun… [the device] will store sufficient electrical energy to light an ordinary house for a week”.

It noted how cheap solar energy could liberate people from poverty, “bringing them cheap light, heat and power, and freeing the multitude from the constant struggle for bread”. The piece went on to speculate how even aeroplanes could be powered by batteries charged by the sun. A clean energy future seemed to be there for the taking.

Vested interests?

Then, according to a report in The New York Herald on 19 October 1909, Cove was kidnapped. The condition for his release required forgoing his solar patent and shutting down the company. Cove refused and was later released near Bronx Zoo.

But after this incident, his solar business fizzled out. Which seems odd – in the years before the kidnapping, he had developed several iterations of the solar device, improving it each time.

I can’t say with certainty if vested interests were behind it. Some at the time accused Cove of staging the kidnapping for publicity, although this would seem out of character, especially since there was no shortage of media attention. Other sources suggest that a former investor may have been behind it.

What is well-known though, is that fledgling fossil fuel companies commonly deployed unscrupulous practices towards their competitors. And solar was a threat as it is an inherently democratic technology – everyone has access to the sun – which can empower citizens and communities, unlike fossil fuels which necessitate empire-building.

Standard Oil, led by the world’s first billionaire John D Rockefeller, squashed competition so thoroughly that it compelled the government to introduce antitrust laws to combat monopolies.

Similarly, legendary inventor Thomas Edison electrocuted horses, farm animals and even a human on death row using his rival Nikola Tesla’s alternating current to show how dangerous it was, so that Edison’s own technology, the direct current, would be favoured. Cove’s Sun Electric, with its off-grid solar, would have harmed Edison’s business case for building out the electric power grid using coal-fired power.

While some scattered efforts in solar development occurred after Cove’s kidnapping, there were no major commercial activities for the next four decades until the concept was revived by Bell Labs, the research branch of Bell Telephone Company in the US. In the meantime, coal and oil grew at an unprecedented pace and were supported through taxpayer dollars and government policy. The climate crisis was arguably underway.

Four lost decades

When I discovered Cove’s story, I wanted to know what the world lost in those 40 years, and ran a thought experiment. I used a concept called Wright’s law, which has applied to most renewables – it’s the idea that as production increases, costs decline due to process improvements and learning.

I applied this to calculate the year solar would have become cheaper than coal. To do this, I assumed solar power grew modestly between 1910 and 1950, and worked out how this additional “experience” would have translated into cost declines sooner.

In a world in which Cove succeeded and solar competed with fossil fuels from the get go, it would have trumped coal by as early as 1997 – when Bill Clinton was president and the Spice Girls were in their heyday. In reality, this event occurred in 2017.

An alternate century

Of course, this still assumes that the energy system would have been the same. It is possible that if solar were around from 1910 and never disappeared, the entire trajectory of energy innovation could have been very different – for example, maybe more research money would have been directed towards batteries to support decentralised solar. The electric grid and railways that were used to support the coal economy would have received far less investment.

Alternatively, more recent advances in manufacturing may have been essential for solar’s take-off and Cove’s continued work would not have resulted in a major change. Ultimately, it is impossible to know exactly what path humanity would have taken, but I wager that avoiding a 40 year break in solar power’s development could have spared the world huge amounts of carbon emissions.

While it might feel painful to ponder this great “what if” as the climate breaks down in front of our eyes, it can arm us with something useful: the knowledge that drawing energy from the sun is nothing radical or even new. It’s an idea as old as fossil fuel companies themselves.

The continued dominance of fossil fuels into the 21st century was not inevitable – it was a choice, just not one many of us had a say in. Fossil fuels were supported initially because we did not understand their deadly environmental impacts and later because the lobby had grown so powerful that it resisted change.

But there is hope: solar energy now provides some of the cheapest electricity humanity has ever seen, and the costs are continuing to plummet with deployment. The faster we go, the more we save. If we embrace the spirit of optimism seen during Cove’s time and make the right technology choices, we can still reach the sun-powered world he envisioned all those years ago.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Sugandha Srivastav receives funding from the British Academy and the Climate Compatible Growth Programme.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.