Jimi Hendrix wasn’t the first teenager to fall under Elvis Presley’s spell. But it was actually his backing band that made the biggest impression. Hendrix was just 14 years old when he saw the King at Sick’s Stadium in Seattle on 1 September 1957. And while he was intoxicated by Presley’s stage show, he found himself irresistibly drawn to guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black and drummer D.J. Fontana. “Those musicians were really something,” he marvelled later. “They made playing music seem like the best thing in the world!”

Already an aspiring guitarist, Hendrix owned just a single-string ukulele at the time, retrieved from a neighbour’s rubbish. He played as best he could by aping Moore’s licks on Hound Dog and others. It wasn’t until the following summer that Al Hendrix, Jimi’s father, bought him a second-hand acoustic guitar for five dollars. Soaking up the music of blues greats like B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Elmore James and Robert Johnson, Hendrix retreated to his room and practised endlessly.

It proved a refuge of sorts from a difficult early life. Born Johnny Allen Hendrix in November 1942, though renamed James Marshall Hendrix four years later, his parents struggled to make ends meet in Seattle. Alcoholism and in-fighting became a fixture of their on-off marriage. They eventually divorced in 1951.

The eldest of five siblings, three of whom were given up for adoption or foster care, Hendrix and his brother Leon were sent to live under the custody of their father. When their mother Lucille died from a ruptured spleen in February 1958, aged just 32, Al refused to allow his sons to attend the funeral.

Hendrix sought to escape through music. He joined his first band, The Velvetones, in mid-1958, though his enthusiasm was dampened by his inability to hear his acoustic guitar amid the noise. A year later, after his father had finally agreed to buy him an electric guitar, a white Supro Ozark, Hendrix had graduated to another local outfit, The Rocking Kings.

Dropping out of high school, his time was spent either in bands or in trouble on the streets. In May 1961, aged 18, he was arrested for joyriding in a stolen car and hauled up before a judge. A counsellor suggested he enlist in the army. For Hendrix, it was a no-brainer. “If I ended up in jail,” he reckoned, “I knew I wouldn’t be able to play guitar.”

After basic training, the teenage Jimi was duly assigned to the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. It was here that Hendrix began to make lasting connections. More committed to his red Silvertone Danelectro guitar than his formal duties, he started playing the army clubs. He soon hooked up with bassist (and fellow serviceman) Billy Cox, who was so floored by Hendrix’s style that he described him as a cross between “John Lee Hooker and Beethoven.” The pair formed a loose ensemble, The Casuals, and began performing at weekends.

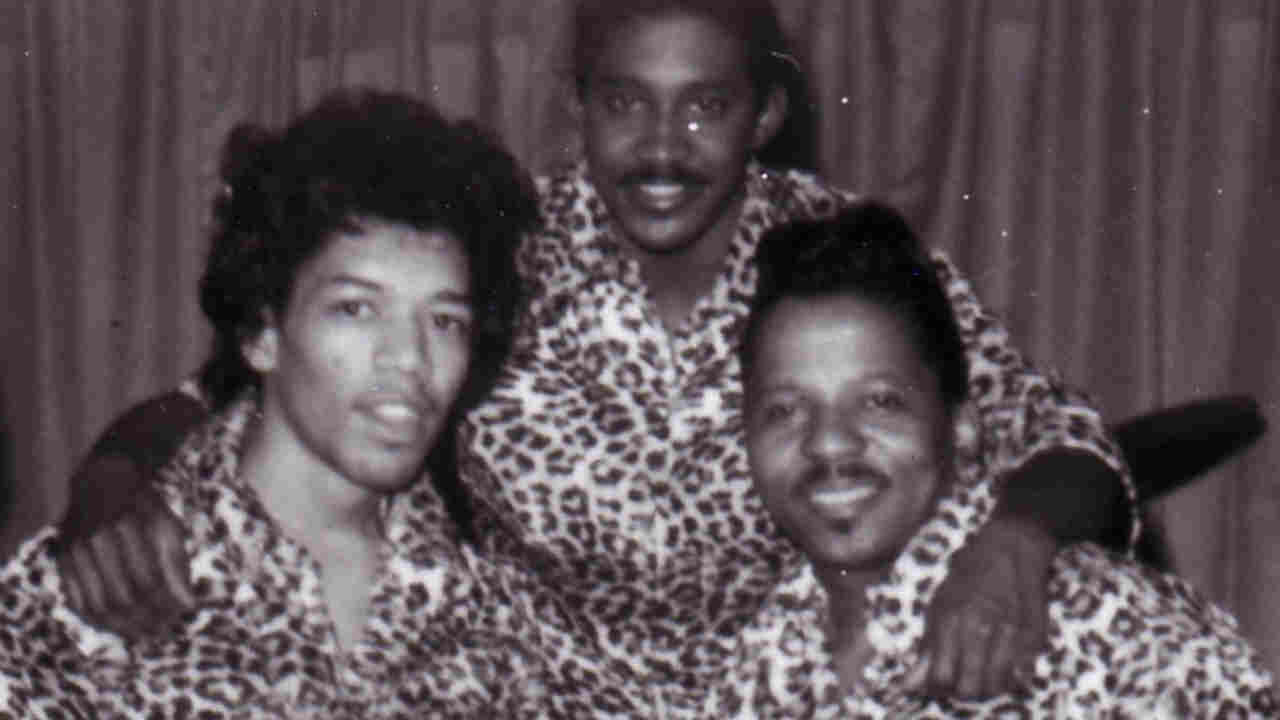

The official verdict on Hendrix’s time in the army was damning. “It is my opinion that Private Hendrix will never come up to the standards required of a soldier,” wrote his platoon sergeant. He was discharged him within the year, freeing him from all distractions. He and Cox took their band, renamed The King Kasuals, to Nashville, where they enjoyed a residency at the Club Del Morocco from late 1962 onwards.

During his time in Tennessee, Hendrix adopted the gimmick of playing guitar with his teeth, inspired by the likes of fellow bandmate Alphonso Young. He also sought a new challenge. While his association with Cox would resurface much later in Band Of Gypsys and The Cry Of Love, Hendrix accepted an offer to join ‘Gorgeous’ George Odell’s touring band. “He was a character from the get-go,” Hendrix told biographer Sharon Lawrence. “He wore a fancy silver wig and flashy clothes. I had nothing to lose.”

This was Hendrix’s entrée into the network of largely Southern venues known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, conceived for black entertainers in the age of racial segregation. The package tour he joined included Aretha Franklin and Hank Ballard & The Midnighters. Before long, Hendrix became a member of The Midnighters themselves, though his flamboyant stage antics brought him into direct conflict with Ballard, who simply wanted him to play what he was told. He was fired after a couple of months.

Hendrix returned to Nashville, finding gigs wherever he could. One occasion saw him supporting Cox’s new group, The Sandpipers, billed as “Jimmy Hendrix and his magic guitar”. Along with Cox, he briefly toured as part of Bob Fisher And The Bonnevilles, before trying his luck in Vancouver as back up for Bobby Taylor. He took part in sporadic recordings for little-known artists like Johnny Jones and Sandra Wright, but couldn’t catch a break.

Money was tight, but the thought of failure made him redouble his efforts. Hendrix wrote home to his father around the time: “I still have my guitar and amp and as long as I have that, no fool can keep me from living. Although I don’t eat every day, everything’s going all right for me. It could be worse than this, but I’m going to keep hustling and scuffling until I get things to happening, like they’re supposed to for me.”

By early 1964 he’d moved to New York City. Having scooped first prize – a princely $25 – on amateur night at Harlem’s famous Apollo Theatre, Hendrix saw his fortunes change. The Isley Brothers invited him to audition. Pitching up at their New Jersey home with everything he owned in a beat-up guitar case, Hendrix duly joined their backing band, the I.B. Specials. He toured with the Isleys all over the US and Canada, during which time he first crossed paths with drummer and future collaborator Buddy Miles, then gigging with Ruby & The Romantics.

Hendrix also joined the Isleys in a New York studio that spring, where they cut the fiery gospel tune, Testify (Parts I & II). He was allowed to express himself with a series of burning lead riffs, but, back on the road, he felt more inhibited. The group’s clean-cut demeanour and regimented stage look didn’t sit well with Hendrix’s frilly shirts, coloured scarves and loose bracelets.

In May 1964, Hendrix snuck off to play guitar on Don Covay’s soulful Mercy Mercy. The single rose to No.35 on the Billboard chart, earning him his first hit. He would teach the main riff to guitarist Steve Cropper during a trip to Stax Studios in Memphis that autumn. “That about knocked me to my knees,” recalled Cropper, who covered the song with Booker T. & The M.G.’s the following year.

Hendrix was already bored with the Isleys by that time and resolved to quit. He reunited with George Odell, who secured him a spot on Sam Cooke’s Super Attractions tour. His trajectory seemed back on the up, only for him to miss the bus one night in Missouri and become stranded in Kansas City.

Odell came to his rescue once again, connecting Hendrix to members of Little Richard’s backing band. With his guitar wrapped in a potato sack, Hendrix bought a bus ticket to Atlanta, where The Mighty Hannibal, with whom he’d played for a short while, made the introductions to his new employer. Little Richard’s glory days were long gone by then, though he was still a popular live performer. Hendrix took his place in The Crown Jewels, his touring band, and hit the road in early 1965.

A stopover in LA brought Hendrix into contact with singer Rosa Lee Brooks. They briefly became an item, with Brooks also enlisting him to play on her single, My Diary (written by Love’s Arthur Lee), and b-side, Utee. It marked the beginning of a warm friendship between Lee and Hendrix, who became one of Love’s biggest supporters.

Back with Little Richard, Hendrix accompanied the rock’n’roll legend in the studio for a searing version of Don Covay’s I Don’t Know What You Got (But It’s Got Me). It’s an astonishing vocal performance from Richard, wringing out every drop of anguish. Hendrix told one interviewer that he wanted “to do with my guitar what Little Richard does with his voice.”

But life in the band was less praiseworthy. Hendrix claimed that he went weeks without being paid, while Richard cited the guitarist’s tardiness and his penchant for trying to upstage him as an ongoing issue. “On the stage he would actually take the show,” Richard told VH1’s Legends. “People would scream and I thought they were screaming for me. I look over and they’re screaming for Jimi! So I had to darken the lights.”

Hendrix was eventually fired after missing the bus one time too many. He’d seen it coming. “There were always problems,” he remembered later. “I wanted to quit.”

Hendrix was temporarily reunited with The Isley Brothers in the latter half of 1965. They played a handful of dates and, in August, headed into New York’s Atlantic Studios to record an Isleys single, Move Over And Let Me Dance/Have You Ever Been Disappointed. But he soon moved on.

Meeting R&B singer Curtis Knight in October ’65, in the lobby of the America Hotel in New York, led to a steadier job. Knight brought Hendrix into his backing trio, The Squires, and recorded a 45, How Would You Feel, the next day. His tenure with the band lasted until May the following year and included a handful of further recordings, including the instrumentals Hornet’s Nest and Knock Yourself Out, both notable for earning Hendrix his first credits as composer.

The arrangement with Knight wasn’t exclusive. Neither were his business deals. Having previously agreed a two-year deal with Sue Records, Hendrix took it upon himself to sign a three-year contract with PPX Enterprises not long after. Not only did it illustrate his naivety in dealing with the music industry, but his involvement with PPX proved damaging. After Hendrix had become a superstar, legal problems ensued with company boss Ed Chalpin, who issued a series of compilations from the guitarist’s time with The Squires. “They were nothing but jam sessions, man,” commented a peeved Hendrix.

In the meantime, his stretch with Knight was interrupted by touring duties with Joey Dee & The Starliters and, in January 1966, a studio date with Ray Sharpe and the King Curtis Orchestra. As the Squires dissolved, Hendrix cut sides with the group’s saxophonist, Lonnie Youngblood, billed as The Icemen. But his main goal was to be out front. “I wanted my own scene, I wanted my own music,” he stated. “I was starting to see you could create a whole new world with an electric guitar.”

His solution was to shift over to Greenwich Village and start his own band in the summer of ‘66: Jimmy James And The Blue Flames. On the strength of his reputation from playing with Curtis Knight, securing a residency at the Café Wha? proved no problem. Word began to build. Among the songs covered by the Blue Flames (whose ranks included future Spirit guitarist Randy California) were two inspired covers that would soon be etched into Hendrix lore: Hey Joe and Wild Thing.

Vogue model Linda Keith, girlfriend of the Stones’ Keith Richards, became a regular at those Village gigs. Convinced of Hendrix’s potential, she invited along the likes of Seymour Stein (who’d just founded Sire Productions) and Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham. Bizarrely, neither of them were sufficiently enthused.

Everything changed when Keith bumped into Animals bassist Chas Chandler, then looking to get into production and management. She took him to the Café Wha? one August afternoon and watched as Hendrix launched into Hey Joe, at which point “he blew Chas’s mind with the first chord.” The rest, as we know, is legend.