Lessons is Ian McEwan’s most autobiographical novel to date. It is the story of a man’s life, but it is also the story of a man making his life into a story. It exemplifies the risks and rewards of living a life shaped from within by the logic of literature.

Lessons – Ian McEwan (Jonathan Cape).

Anyone familiar with McEwan’s extensive, award-winning oeuvre will know that his resort to personal material is not for lack of imagination. He is, by any standard, a master of style and invention. It is hard to class his novels within a genre because he has forged his own – one that combines crisply realist surfaces with sudden excursions into the darkest corridors of the mind.

These hallmarks persist in Lessons, but the inclusion of autobiographical details – like McEwan, the novel’s protagonist grows up in North Africa in a British military family and discovers late in life that he has a brother – is a new experiment in vulnerability.

The novel’s central character, Roland Baines, reveals a writerly consciousness at work. Roland is attempting to make sense of his life as lessons – stories of cause and effect. The solipsism and pathos of this project are on display, along with a glimmer of grace.

A labyrinth of cold sorrow

Lessons begins with a piano lesson remembered with sensory immediacy. Bach’s prelude seems to the 11-year-old Roland “like a pine forest in winter […] his private labyrinth of cold sorrow. It would never let him leave.” His piano teacher, Miriam, pinches the boy’s thigh, slips her fingers towards his crotch, and strikes his knee with the edge of a ruler. She styles this abuse as a lesson.

As an isolated and obsessed 14 year old, Roland seeks out Miriam during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He wants to experience sex before he is “vaporised” by nuclear war. But the world goes on, and so does their intoxicating and destructive relationship.

A narrative leap locates these memories in the mind of the adult Roland, a sleep-deprived father to a young infant. His wife Alissa is missing and he is a suspect in her disappearance. Who is to blame? And what is the point of the pain? From these formative betrayals by women – one a controlling sadist and one an absconder – Roland tries to extract some answers.

There is something suspicious about this narrative set-up. In their physical absence, Roland invents the power of these female characters. Like witches in fairy-tales, they carry the destructive drives.

This displacement frees Roland to present himself as a talented person living an inconspicuous existence. He commits to the loving labour of raising their son, while Alissa goes on to become an award-winning novelist. The writerly consciousness is thus split across two very different kinds of life choice, but it is disappointingly conventional that the female characters are made to carry the destructive ego traits. Somehow Roland’s story gets told, but it costs him far less than Alissa to tell it.

But there is a dark edge to Roland’s writerly mind too. A poem in a notebook the police took from his desk refers to murder and burial. Roland explains to the detective that this is figurative language used to express the end of a different relationship – the liaison with Miriam – and scoffs at the clumsy intrusion by the police:

The street-level forces of law and order were long-ago typed into the culture as Shakespeare’s Dogberry. This visit would be an exquisite tale, one that Roland would work up and tell, as he had before.

The passage throws suspicion on Roland. In Much Ado About Nothing, Dogberry’s police force does apprehend the villains, albeit accidentally. Moreover, Roland’s propensity to “work up” tales is laid bare. McEwan lets the author’s hand flicker into view.

Even more disconcertingly, Roland says to himself: “The grave containing her remains did not exist.” The plain meaning is clear: there is no grave. But the word-order puts “the grave” before the reader’s imagination before making it disappear. What, we wonder, is the extent of the damage done inwardly to Roland? Can this keeper of secrets keep secrets from himself? The sliver of doubt is thickened by self-questioning: “Why even tell himself this?”

À lire aussi : Philosophy, obsession and puzzling people: Julian Barnes' new novel explores big questions

A storytelling habit

Roland’s storytelling habit entails a desire for narrative epiphanies, as for sex, with unknown limits. Alissa’s wry comment – “this piano teacher […] rewired your brain” – raises the possibility that the novel’s shaping consciousness is indelibly damaged.

Roland might not be a murderer with a mind half in shadow, but he has a compulsive habit of burying and exhuming the past to make the present bearable. He is trying to mitigate life’s painful confusion. He shares this habit with most human beings, of course. The key difference is that Roland’s life, because it is a narrative invention, has more returns and more plot resolution than most real lives.

He eventually catches up with both Miriam and Alissa. From Miriam, he receives a pleading apology. He takes control of their story by deciding that he won’t bring a case against her because “this wasn’t the same woman”. Alissa, with her amputated foot and morbid addiction to nicotine, offers another scene of pathetic resolution. Roland sees that her choice of a writing life has cost her a relationship with their son. Both women are diminished by the narrative – a point sharpened by the title of Alissa’s award-winning novel: Her Slow Reduction.

Surprise returns trigger new hope and old pain. Roland is reunited with his lost brother – a plot point implausible enough to be from real life. The eager, awkward regard in which the two ageing men hold one another is depicted with great gentleness.

Daphne, the stalwart friend of his early single-parent days, also returns when they are in their sixties. One night as they sit “shoeless by the fire”, Roland asks her to marry him. The epiphany seems to have arrived:

Everything glowed […] This was how to steer life successfully Roland thought. Make a choice, act! That’s the lesson.

But this instant of empowering volition is eclipsed only 24 hours later when Daphne tells Roland she has received some test results:

It’s cancer, grade four […] It’s everywhere! I don’t stand a chance. I’m so scared.

The very next page begins:

He lifted it from the drawer where he kept his sweaters and placed it on his desk. It was a weighty ceramic jar.

The leap from Daphne’s living fear to Roland handling a jar of her ashes is a cruel jolt. It is two years after her death and he is preparing to return to Scafell Pike to scatter her ashes. Skipping the pain seems a cowardly, solipsistic design – no one in the novel gets to be as complex and concentrated a consciousness as the protagonist. Daphne’s last chapter of life unfolds through Roland’s memory. The narrative follows the contours of his mind, not the sequence of days.

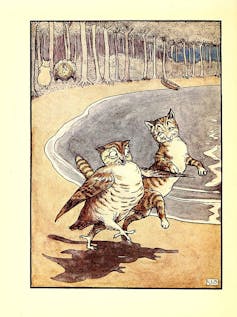

Roland’s granddaughter Stephanie enters late in the novel. As a new character, she permits fresh returns. Their shared story-within-the-story is Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat – a “beautiful impossible adventure” – which Roland had read to his son Lawrence, who in turn reads it to his seven-year-old daughter. Stephanie begins to learn and recite the poem during a COVID lockdown.

In the novel’s closing pages, Stephanie’s obliviousness to a heavy-handed message in a different bedtime story makes Roland reflect that it is a “shame to ruin a good tale by turning it into a lesson”. He then confides in her that

there’s a pretend book I want to read. It’s very interesting and so enormous that I don’t think I’ll ever get to read it all.

He tells her that it has “everyone in it, including you”.

Here is the familiar McEwan coup: a narrative bent back on itself. Before he is led off the stage of his own story by Stephanie, Roland (or McEwan) shows that the controlling hand of the narrative retains masterful control even when letting go.

The final return comes after the story is complete. In a postscript, McEwan reveals another inter-generational story of reading and writing: “Finally, my thanks to my English teacher, the late Neil Clayton, who insisted that I used his name unchanged”. Clearly, the lesson that has shaped McEwan’s literary imagination is the one same that sticks for Roland: in the patient processes of living and writing, epiphanies arrive rarely and unbidden. They are less like a lesson and more, like McEwan’s novel, a gift.

Kate Flaherty works for the Australian National University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.