In 2015, marking the reissue of Peter Gabriel’s first four solo albums, Prog looked at how those remarkably different works illustrated his development beyond Genesis and his securing of a unique place in the history of progressive music.

In the six years from 1977-1982, Peter Gabriel released four albums that were to define him as one of the great pioneers of British rock music and set him on his course to becoming a global superstar. They are the sound of freedom: each album a step further in shaking off his Genesis past, in which every decision had to be made by committee. This now was most definitely his very own show.

With his quartet of self-titled albums, Gabriel brought progressive rock out of the 70s and pre-empted how the genre would move forward. By the time of his third album in 1980, he had struck a template that has lasted him to the present day. He drew on some of the best players possible, and the atmosphere of creativity fostered incredible experimentation.

With each record you hear his confidence grow. From the first album, where he was being happily taught by studio master Bob Ezrin; to the second, where he was working in partnership with Robert Fripp; to his third and fourth, which put him very much in the driving seat, his producers (Steve Lillywhite and David Lord, respectively) absorbing and capturing his ideas.

After his final show with Genesis in April 1975, Gabriel did exactly what he said he would; he withdrew from the music business and spent more time with his family. It absolutely fascinated the papers that a star – suddenly about to achieve what he had ostensibly craved – would turn his back on it at the age of 25 to pursue domestic life.

Although he had dabbled in music since leaving the band, by mid 1976, Gabriel was ready to return to the fray. He began casting his net for a producer, liking the idea of using someone outside the UK production system, with different ideas and a wider vision. Todd Rundgren was considered; but Ezrin, who had made his name with his productions for Alice Cooper and Kiss was chosen, partially because of his work on Lou Reed’s Berlin, his critically lauded, black as pitch 1973 masterpiece.

Ezrin was to select virtually all of the album’s players, trusted session hands used to working at speed with demanding artists. “I had developed this crew of regulars that I would work with,” the producer said in 2013. “I put them together for when I worked with solo artists who didn’t come with their own band.”

It was through Ezrin that Gabriel met one of his longest serving and most trusted players – bassist Tony Levin. Gabriel chose two players on the album: one was keyboard player Larry Fast, who had worked with Rick Wakeman. The other was his old friend, ex-King Crimson leader Fripp. “He thrived on the characters,” Ezrin said. “He negotiated with me, asking if he could have one Brit: I felt we were doing a sports deal, like a football club, needing a striker. I agreed; he said, ‘Can it be Robert Fripp?’ It was an exciting thing that he brought Robert into the fold, and Robert perfectly rounded out this group of misfits and musical outlaws.”

Gabriel relocated to Nimbus Studios in Toronto to work. The sessions were conducted in a business-like fashion: “Bob was a very forceful individual back then,” Fast noted. “He actually wore a whistle, like a coach, around his neck while he paced the studio during song rundowns.” With such a pedigree of performer and the high-end producer, it’s little wonder that Gabriel’s debut album is the closest he ever came to becoming a straight down-the-line stadium rocker. From the Genesis-like Moribund The Burgermeister to the slamming rock of Down The Dolce Vita, the album is rather splendid and sometimes daft.

Robert Fripp was keen to get everything fresh. We kept a lot of early takes and kept the production very dry. The second album is more spontaneous

Peter Gabriel

Gabriel wrote his first solo classic in Solsbury Hill, a record that proved he had more than enough commercial nous to go it alone. As he said at the time, “It’s about being prepared to lose what you have for what you might get, or what you are for what you might be. It’s about letting go.” Its optimism is heartwarming, and its manifesto is clear: To succeed, you have to take risks.

Here Comes The Flood was remarkable. He was fascinated with short wave radio, and was amazed how signal strength became stronger as daylight faded. All of this fed into the tale of barriers in individuals’ thought processes being broken down so anyone can see into other people’s minds; and, as Gabriel said, “those inclined to concealment would drown in it.” It is a brooding, intense experience that demonstrated the distinctiveness of his writing.

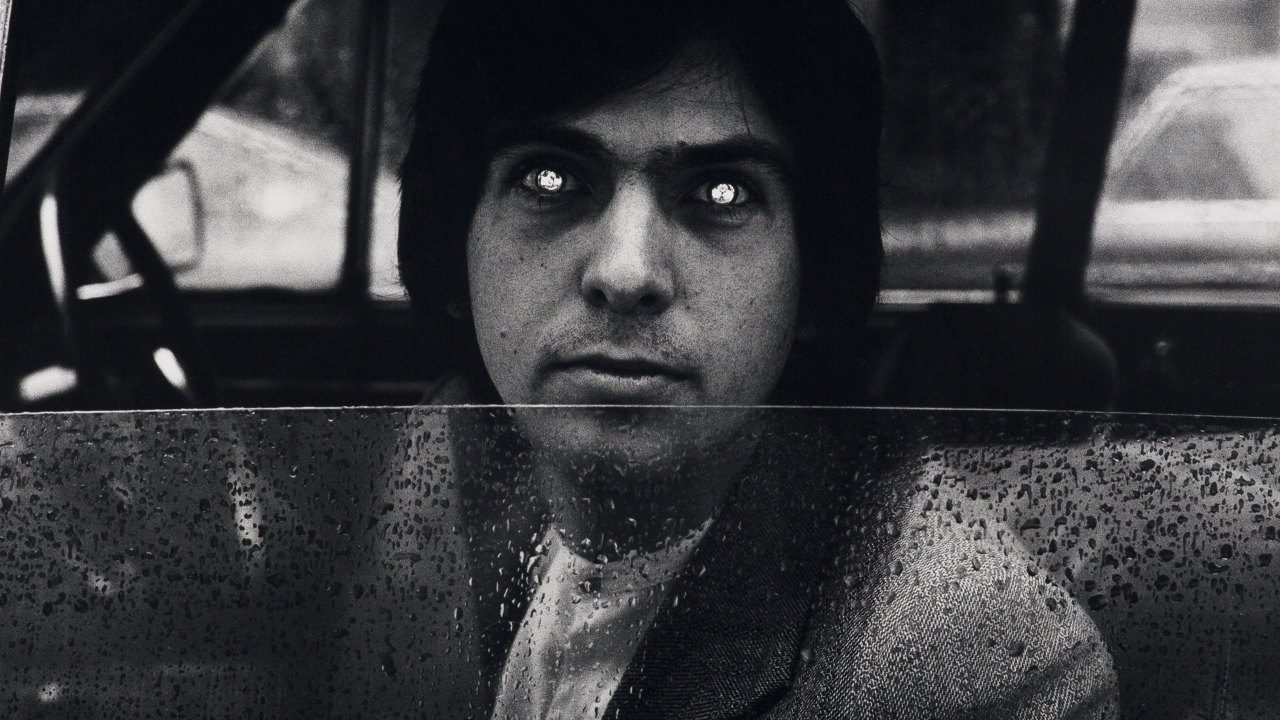

The sessions finished in Toronto with a riotous meal and prize-giving ceremony at the Napoleon Restaurant. “I gave out gifts to acknowledge everyone’s contribution,” Ezrin said. “Peter was dressed in his white three-piece suite with a black shirt and a hat and he wore his ball-bearing contact lenses behind dark glasses. I gave Tony Levin a tuba, and I gave Fripp a beautiful gold antique pocket watch on a chain.” The assembled players then all sang an a capella version of the album’s barbershop quartet number, Excuse Me.

“I really wanted the first record to be different from what I’d done with Genesis, so we were trying to do things in different styles,” Gabriel said in 2015. “A bit of barbershop, which Tony Levin helped with; there were more bluesy things; a variety of songs and arrangements that were consciously trying to provide something different than what I’d done before.”

The album, simply titled Peter Gabriel, was released in the UK on February 25, 1977. Hipgnosis designed a heavily-colourised distant and mysterious sleeve that featured Gabriel sitting in Storm Thorgerson’s rain-soaked Lancia Flavia. It gave the album its simple, colloquial name of Car. With a tag-line of ‘Expect the unexpected on the new Peter Gabriel album,’ it reached a respectable No. 7 in the UK and No. 38 in the US. Rolling Stone said, “This is an impressively rich debut album. And I still don’t know what to expect from him next.”

After extensive touring, his second album – also titled Peter Gabriel – followed in June 1978, with Car guitarist Robert Fripp as producer. “I really like Two; it takes a while,” Gabriel’s long-term engineer, Dickie Chappell, says. “I think Peter thought it was made too fast. There’s some great songs on there and it has its own atmosphere; it’s very bright, brittle sounding.”

This album was recorded at the quickest pace of any in his career. As Eric Tamm notes in his biography of Robert Fripp, “If Peter Gabriel 1977 sounds like it was recorded in a heavenly cathedral, Peter Gabriel 1978 sounds like it comes out of a dingy garage.”

The album was to be known as Scratch because of its distinctive, Hipgnosis-designed sleeve. Although partially recorded at Relight Studios, Hilvarenbeek in the Netherlands, its sound primarily was that of New York, where the remainder of the album was recorded at the Hit Factory. It’s sparse, harder and emotional. Fewer people were in the studio and the band gelled: Levin, Fripp and Fast were back. Jerry Marotta came in on drums. Among others, Roy Bittan from the E-Street Band added his unmistakable piano lines.

“Robert was very keen to get everything fresh,” Gabriel said in 1978. “We kept a lot of early takes and kept the production very dry. The second album is more spontaneous.” It’s the Peter Gabriel album that few seem to know. Standout moments include the sea of synthetics that introduce On The Air. Its five and a half minutes are neatly answered by the two-and-a-half minutes of D.I.Y.; with its crisp snare snap and acoustic guitars, it’s another plea for independence, chiming with the ‘do it yourself’ ethos of the New Wave movement.

White Shadow is subversive AOR, it arrives with all of Fripp’s floating ambience based on Fast’s swathes of synthesizers. Exposure is one of the album’s highlights. Introduced by Fripp’s unmistakable guitar, it is a dense, brooding funk that appears from nowhere and seems to linger forever.

Scratch was released in June 1978. Sounds concluded, “This new Peter Gabriel album is absolutely it. It hasn’t left my turntable yet and doesn’t look like it’s going to. It couldn’t happen to a finer artist. Just listen.” The to-the-bone subject matter and experimental playing demonstrated Gabriel’s growing confidence. Writing in the NME, Nick Kent said: “closer to the root of the album, there’s a purity of strength to the songs individual enough to mark Gabriel out as a man whose creative zenith is close at hand.”

Steve Lillywhite and Hugh Padgham provided a very good balance in coordinating and capturing Peter’s creativity without impressing their own obvious stamp on it

Larry Fast

The album’s supporting tour saw Gabriel and his band dressed in worker’s fluorescents and guesting at high profile festival gigs with The Stranglers and The Boomtown Rats. Gabriel shaved off his hair. He was stripped clean, a symbolic shearing of the lamb. “People react to a shaved head differently to how they do to a soft hairy one,” he said, with some understatement.

“I tried to do a lot of things to separate me from Genesis,” he told Uncut in 2012. “Sometimes you’d see people leave bands and do watered-down versions of what the band had done. I was determined not to do that. I was keen to get a new audience. It took me until album number three before I found an identity.”

“It all starts to come into focus on the third album,” Dickie Chappell notes. “It’s my favourite… there is something about the arrangements and the harmonies used; the sound is pretty nuts.”

Produced by Steve Lillywhite, it features notable contributions from Kate Bush, Phil Collins, Paul Weller, Fripp, Dave Gregory and future Gabriel stalwart David Rhodes. Recording began in earnest when, after demoing tracks and ideas in Bath, Gabriel located to The Townhouse in London. His choice of producer Lillywhite and engineer Hugh Padgham was pivotal – bringing in a young team meant that ideas could easily flow.

“Steve and Hugh provided a very good balance in coordinating and capturing Peter’s creativity without impressing their own obvious stamp on it,” Fast says. The album featured a considerable amount of innovation. Intruder was Gabriel at his most sonically adventurous. He was determined not to have any cymbals on the album, finding them too splashy and detracting from the core rhythm. Gabriel’s motto when recording the album was simple: no middle ground.

The loud, aggressive drum sound of Intruder – played by Collins and recorded by Padgham – is the first thing the listener hears. The pair’s experimentation at Gabriel’s insistence set a template for the 80s pop to follow. “I remember Phil coming in to the rehearsals for Duke with a tape of the drum loop they’d done,” Gabriel’s ex-Genesis bandmate Tony Banks recalls. “With the gated reverb. Phil played it to us, and he told us Peter was writing a song on top of it. I thought it was fantastic.” The record had a cavernous vacancy that could at once be filled with eerie otherworldly noises, most often Gabriel’s vocal tics, or random percussion.

Ahmet Ertegun suggested that Peter might have had some sort of a breakdown during the writing of Melt

Gail Colson

If the opening wasn’t strange enough in itself, the record swooped into No Self Control, an unrelenting view of schizophrenia and paranoia. Gabriel’s maniacal spoken-sung whisper is supported by the track’s insistent backing vocals, provided by his new friend and collaborator, Bush, who was also to add vocals to Games Without Frontiers.

I Don’t Remember demonstrated how the new toy, the Fairlight CMI synthesiser, could be incorporated into conventional rock, adding the sounds of bricks banging together and milk bottles smashing, adding to the otherworldliness of its sound. Gabriel was one of the first musicians in the UK to use a Fairlight, which, within a matter of years, would completely transform the way music was made.

The synth – invented in Australia and costing £10,000 – could sample natural sounds and play them back at a variety of pitches and tones. Gabriel invested in Fairlight and persuaded his cousin, Stephen Paine, to come in with him, establishing the company Syco Systems to import and distribute the instruments in the UK.

“Peter was like the Remington guy,” Chappell laughs. “It was a revolution in sound; hip hop wouldn’t have been hip hop without the samples; it led to producer technology; So Melt (and 4) are a bit of a landmark in the way that people then went on to make music.”

Melt is full of highlights – Family Snapshot is one of his most emotional performances; And Through The Wire has a power pop edge thanks to Paul Weller’s guitar chords. Games Without Frontiers was chosen as the album’s lead single. Gabriel was inspired by the daftness of primetime BBC TV programme It’s A Knockout.

Allegedly, French President Charles De Gaulle commented that a fun competition between everyday people of France and Germany would lead to greater understanding between the countries, inspiring the programme. Gabriel thought the symbolism of the show was ripe for exploring, demonstrating that all of this jollity cloaked simmering resentment. One of the best assessments of the futility of aggrandising nationalism ever to reach the UK Top Five, the song offered

a fine example of Gabriel’s new sonic landscape. He could experiment and still deliver one of the biggest hits of his career.

And then there’s Biko – the track that marked the true beginning of the next phase of his career. Finding rock rhythms limiting, he hit upon this hypnotic African-inspired pattern. But it was the subject matter that really was a departure. He had noted in his diary the death of student activist Stephen Biko at the hands of the South African police in September 1977. Like many white liberals with an awareness of events in South Africa, Gabriel was shocked by the brutality and the subsequent cover-up by police, and decided to capture his thoughts in song.

He was acutely aware of his lack of authenticity to become a champion of causes in far off countries – but that in no way blunted his passion and sincerity for the subject. But the lyrical content would have meant nothing without the remarkable musical setting he and his team put together to support it. With its portentous opening drum rhythm (inspired by the theme music to the Stanley Baker film Dingaka) and drone guitar played by Rhodes, this was very different to anything Gabriel had recorded to date. It was probably the ultimate expression of the album’s ‘no middle ground’ policy. Biko set him on a course that would see Gabriel become one of the most impassioned campaigners for civil rights in popular music.

On Melt the Fairlight was the icing on the cake. On the fourth album it was the cake on many tracks

Larry Fast

The album was released on May 30 1980. For its distinctive sleeve, Hipgnosis created one of Gabriel’s most enduring and disturbing images, manipulating the images from a Polaroid camera when the ink was still wet. It produced strange, wayward and distorted pictures: Gabriel’s face was melting in front of his audience. He looked like a cross between a bizarre candle and a relief map of high ground. As a result, the album picked up its colloquial title, Melt.

The lean and gripping release was rapturously received. It went to No. 1 in the UK in June, where it remained for two weeks, giving Gabriel his first chart-topper. In the US, the album was infamously rejected by Atlantic, “Ahmet Ertegun suggested that Peter might have had some sort of a breakdown during the writing of it,” Gabriel’s then-manager Gail Colson said. Dave Marsh, writing in Rolling Stone, said on the album’s eventual release via Mercury in September 1980: “Lucid and driven, Peter Gabriel’s third solo album sticks in the mind like the haunted heroes of the best film noirs.”

In mid 1980, Gabriel retreated to Bath and began work on his next album with producer David Lord. A considerable amount of money was spent on equipping the studio at Gabriel’s home, Ashcombe House, aka ‘Shabby Road.’ He allowed TV cameras to capture his work in progress. Little did they know that the album would take 16 months to complete. The result was aired on October 31, 1982; Gabriel was elevated to the august band of musicians who were featured on the Melvyn Bragg-fronted prestigious UK arts programme The South Bank Show. The documentary caught Gabriel’s methodically painstaking processes on camera.

“David Lord came from a classical background and had the same high standards for audio excellence,” recalls Fast, who returned for his fourth album with Gabriel. “But he continued to let Peter take his own creative lead while quietly corralling the bits together as the ideas took form. On Melt the Fairlight was the icing on the cake. On the fourth album it was the cake on many tracks.”

It was a painstaking, detailed approach. Ideas were constantly being worked out; Lord and Gabriel were left with 27 16-minute tapes, and over seven hours of material. There were multiple versions of 18 separate songs, several of which were running at over 10 minutes in length. Gabriel, Lord and Fast then spent three further months piecing everything together.

The subject matter was mature and intense: The Rhythm Of The Heat was one of the first ideas that Gabriel brought into the sessions. He’d read Carl Jung’s book Symbols And The Interpretation Of Dreams. To understand the native psyche, Jung joined a group of drummers and dancers in Africa and became overwhelmed with fear. Gabriel was fascinated – in the song’s frantic, hypnotic rhythms, he attempts to capture this accelerating panic.

Car is Peter unsure of how to make a record; Robert Fripp gave Peter more control with record two; Melt is ‘I know what I’m doing now’ and Security is hitting maturity

Dickie Chappell

San Jacinto looked at the clash of cultures around the Native American and the world in which they live. Shock The Monkey sounds hit parade after all that – and indeed, it gave Gabriel his first US Top 40 single, propelled by its strange, otherworldly video, directed by then-hot video director Brian Grant. After a slow build, Lay Your Hands On Me gives way to an impassioned plea for intimacy. Evoking a dream-like rapture, the beautiful ambiguity of the lyric is bolstered by the Biko-like drumming onslaught and mass vocals.

There was a great deal going on in Gabriel’s world around the release of Security – he had instigated the first WOMAD Festival in July 1982, an artistic triumph and a financial disaster. When his old bandmates in Genesis heard of Gabriel’s predicament, they proposed a one-off reunion concert, Six Of The Best, at Milton Keynes Bowl that October (which was of course to prove a great, if very wet, success).

Security (as it was titled in the States at the request his new label boss David Geffen) was released in September 1982. Reviews were mixed. NME’s Gavin Martin wrote, “What is it that makes Gabriel and his ilk think that to address misery and depression the artist must sound miserable and depressed?” Yet Richard Cook as part of his NME interview with Gabriel at the time said saliently, “It is Gabriel’s first step at repositioning the heroic pretensions of rock.”

“The third album was brilliant, and I thought the fourth album was probably slightly better,” Tony Banks was to say. “In terms of composition it was wonderful. San Jacinto is probably my favourite of Pete’s tracks. I would have been a big fan of Pete’s even if I hadn’t known him.”

The tour to support Security was large, and helped build Gabriel’s fanbase in the States. Characteristically cryptic, the shows were entitled Playtime 1988, and they finally found the balance between his rejection of his Genesis persona on his early tours, and greater theatricality. The show was engaging and melodramatic. Working with Levin, Rhodes, Fast and Marotta, the band settled into the North American tour, riding on the wave of goodwill that the success of Shock The Monkey had provided. It was to be the final tour on which Gabriel hid behind any mask or make-up – within two years, Peter Saville would be supervising clean-cut photoshoots for him, and So was just around the corner.

The first four Gabriel albums are the foundations on which his solo career rests: “Car is Peter unsure of how to make a record,” Dickie Chappell says. “Bob came along and took Peter under his wing and guided him through; Robert gave Peter more control with record two; Melt is ‘I know what I’m doing now’ and Security is hitting maturity. There was definitely a different process happening then. Now Peter divides his time between music, human rights and technology; he’s definitely in a different chapter.”

Between 1977 and 1982, Gabriel set a high benchmark. Never have four consecutive albums by the same artist had such different atmospheres. Today, Car, Scratch, Melt and Security still sound contemporary and all still invite the listener to expect the unexpected – a sharp reminder of a different time.