Brendan Woodhouse knew he was in a race against time as his speedboat plunged through 10 miles of choppy Mediterranean waves.

For in the water ahead, their lives ebbing away, were 55 men, women and children.

They had travelled in hope of a new, safe life but their flimsy inflatable had sunk.

Now, covered in fuel burns, these refugees – two heavily pregnant – who had escaped war, torture and human trafficking, were suffering extreme exhaustion, hypothermia and were close to death.

Brendan, a volunteer with the German Sea-Watch organisation, says of the April 9 incident: “It took us over half an hour to get there – a speedboat can only go so fast.

“Tragically, we were too late to save 17 and nine of the people we got to safety had seen family members drown.

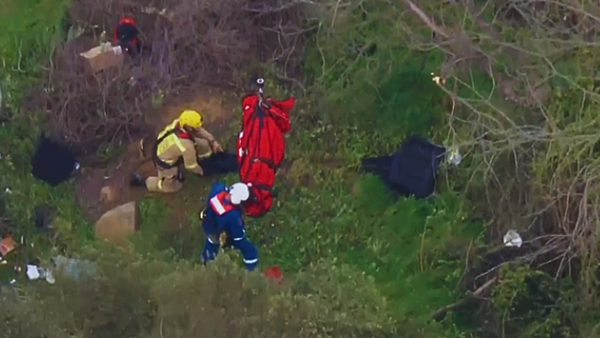

One 17-year-old had lost his 19-year-old brother. We had very serious medical cases who needed immediate evacuation by helicopter and the Italian coastguard.

“Seeing people drown in front of you is difficult to deal with but my suffering is secondary.

“The main focus is on treating the injured and keeping them alive.”

Brendan, 46, from Matlock, Derbys, has worked with refugees since 2015, first going to Calais to take donations to camps there, before taking part in rescue missions at sea.

He was asked to join Sea-Watch last year after he saved an Afghan baby girl from drowning off the Greek island of Lesbos.

Since then he has taken seven spells of annual leave from his job as a fire fighter to join the group.

Deploying larger surface vessels as well as speedboats, Sea-Watch patrols 24 miles off Libya, using radar, binoculars and intel from planes to rescue migrants in distress.

As we currently mark Refugee Week, Brendan is revealing the heartbreaking scenes he has seen in an attempt to raise awareness.

He says: “A lot of people on the boats get bad burns caused by the mixture of fuel and salt water. This has a corrosive effect on the skin.

Remembering the April 9 rescue, he adds: “This time we had a man who had been swimming among the fuel and he was covered in burns.

“The first thing you need to do is give these people a fresh water shower to clear the salt water.

“Then there were some people with signs of secondary drowning.

“Salt water attacks the lungs making victims breathe froth and foam from

the mouth.

“The situation was appalling. We have to deal with the medical problems first, making sure they are fed, watered and kept warm with blankets.

“Then you have to deal with the psychological trauma.

“I want to live in a better world than this.

”Nobody deserves to drown at sea.

“These are human beings like you or me who have all been exploited in some way.”

The people Brendan helped rescue – mainly from Africa and the Middle East – were trying to travel to Europe via Libya.

Brendan, given a medal by the Fire Brigades Union for his lifesaving work, says the people smugglers who send them out don’t care whether they survive the crossings or not.

He adds: “They nearly always come without lifejackets and the very few you do see are fake.

“Most who survived in April were either strong swimmers or had found a tyre to cling to.”

Under a 2017 deal, the EU pays Libya to intercept refugee boats and return migrants to detention centres in North Africa. Since then, more than 82,000 have been intercepted.

When Brendan and his colleagues arrived at the April incident the Libyan coastguard had got there first, causing huge panic among the refugees.

“It’s always concerning when we hear the Libyan coastguard are there because

they normally take them back to the country,” says Brendan.

“These people we were rescuing are really frightened and vulnerable and need protection.

“They don’t make the choice to enter these boats lightly. They know one in 40 of them is likely to drown.

“One woman who had been saved by the coastguard jumped back in and tried to swim to our speedboats.

“She’d almost drowned once but had gone back into the sea so she wouldn’t be returned to Libya.

“Does that not say something to people that the fear the refugees have is very real?”

Brendan says that under international maritime law, the rescuers’ legal duty was to take the migrants to the nearest safe port – either Italy or Malta.

However, he says both countries have previously refused them entry, something which happened again in this case.

“We first tried to take them to the Italian island of Lampedusa but weren’t allowed in.

“We then had to move further on to Sicily to drop them off.

“There they entered quarantine before being taken in for asylum processing.

“The majority of the people going through this do actually receive refugee status, which shows that they have fled from something terrible.

“You don’t get that status if you haven’t gone through this.” In this year alone, as Home Secretary Priti Patel presses ahead with plans to deport refugees to Rwanda – despite her initial attempts being thwarted – more than 3,000 have drowned trying to reach Europe and safety.

Brendan’s experiences as a Sea-Watch volunteer lays bare the human cost of the crisis. The April incident happened on his final mission of this year.

A few days before he returned to the UK there was further tragedy when another boat sank, this time with 90 aboard.

Brendan says: “This time they were too far away for us to do anything about it.

“Of the people on board, just four survived.

“They had been at sea four days. European governments are trying to create a deterrent of death by drowning and it’s very cruel when you see it first hand.

“When you speak to a 17-year-old who is asking you how to tell his mum that his teenage brother is dead, then the brutality of these policies is very clear to see.”

Brendan says that over the years he has spoken to thousands who have made these deadly journeys but one story sticks in his mind.

It is that of Doro Goumaneh, originally from the Gambia in West Africa.

He recalls: “This man had travelled across the Sahara in a group of 170 but fewer than 100 made it from Niger to Algeria. He then had to get from Algeria to Libya.

“He was one of 36 making that crossing but only 16 succeeded.

“He tried to get from Libya to Italy and was captured by the Libyan coastguard and sold to a militia by the people who caught him at sea.

“They tortured him in a ransom call they forced him to make to his mother.

“These things are happening in Libya all of the time – and the refugees endure all of that to try again.

“Most people who make it to Europe do so on their fourth or fifth attempt.”

Brendan is now working with his Gambian friend – whom he rescued as he made his fourth crossing attempt in 2019 – on a memoir which they are currently crowdfunding to have published. While many refugees are often demonised and called “illegal”, Brendan says it is only a

luck of our birth that saves Europeans from the same fate.

“When I returned to the Britain in April I entered Italy no questions asked despite us no longer being part of the EU.

“I then flew to the UK easily, in the same way I could fly to basically any other country in the world with my passport.

“Arriving in Birmingham, I saw a desk that said ‘Ukrainian arrivals’.

“It was really pleasing to see that we are welcoming to them and the suffering Ukrainians are enduring is taken seriously, that is exactly as it should be.

“But it brought up questions in my mind: Why aren’t we giving this same generous welcome to people from countries such as Afghanistan, Syria, and South Sudan?

“The upsetting conclusion I have come to is because they are not white.”

To those dehumanising refugees, Brendan has a simple message.

He says: “If anybody spent half an hour on the Sea-Watch boat talking to people who had arrived from Libya, their views would dramatically change.

“Think about it. How would you want us to treat you or your relatives if they faced the danger of drowning out at sea.

“If it was happening to me or my kids, I would want somebody to rescue me.

“By allowing ourselves to dehumanise these people, we dehumanise ourselves.

“Why are we not thinking of them as what they are – human beings in real, present danger?

“We should simply treat these people how we would want to be treated ourselves should we ever be in the same situation.”

* To give to Sea-Watch and to find out more, visit sea-watch.org/en/donate For more info on Brendan and Doro’s book, see unbound.com/books/doro