It was a few years ago that I noticed Posh Spice was getting a bit posher. In the life and times of Victoria Beckham, this was long after the Spice Girls and her artistic collab with Dane Bowers. It was post-Wag. Post-Heat. This was amid her (current) run as Victoria Beckham: Fashion Mogul. Gone was the sharp, ice-blonde bob and that knowing self-deprecation; in their stead were clean lines and a polished seriousness. And that original voice of hers – loud, bolshie, lots of dropped consonants – was phased out in favour of something else. Slower. Airier. Clipped.

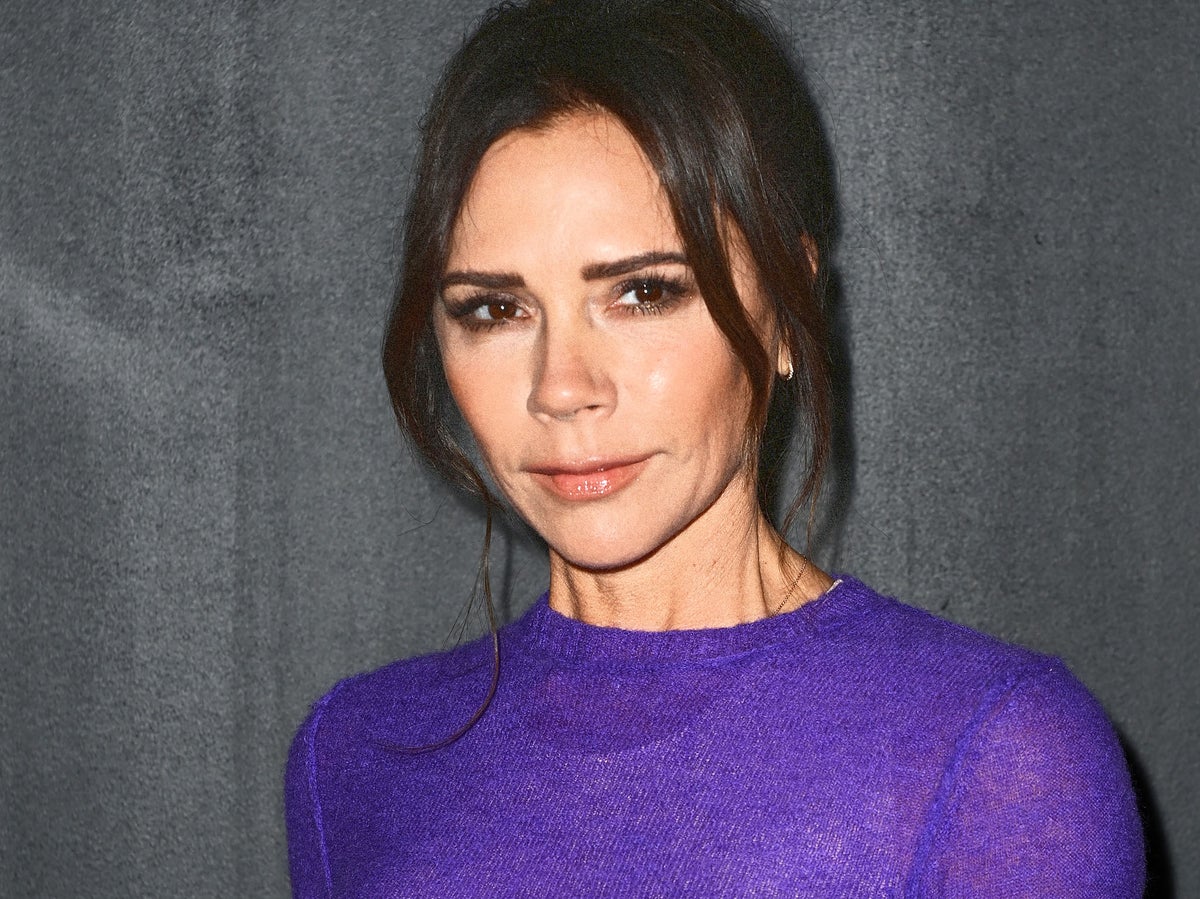

Weirdly, this change in voice seems to have only just been picked up. Over the weekend, Beckham posted a make-up tutorial to her Instagram, demonstrating how to achieve her “signature smokey eye” with one of her beauty products. Viewers, though, were distracted by her voice. “I love her but I swear she didn’t always sound like this,” one person commented. “I know she’s Posh Spice but girllll [sic].” Another added: “Sorry but [she] tries too hard with her accent, not natural at all.”

Most of the comments under her video followed a similar track: nothing, it seems, brings together a bored, miserable public quite like an opportunity to kick a Beckham. But I also felt an unexpected pang of recognition. For probably the first and only time in my life, I had something in common with Posh Spice: I, too, have an artificially crafted voice and an accent of unknown origin, a product of some indiscernible mix of misguided embarrassment and self-preservation. I’m guessing a lot of us do.

When I was 18 years old, I was told that my natural Bristolian accent – not quite Vicky Pollard, but at least vaguely Stephen Merchant-esque – projected my status in the world, and that I would need to “fix it” in order to get anywhere. This was during a Shakespeare-reading class at a fancy-pants drama school I was attending, which also operated as a kind of hellscape of chronic humiliations. There was the teacher who informed me I needed to “speak properly”. Another who swiftly picked up on every hard “r” sound I produced. Yet another, who asked me what area of Bristol I was from before recalling how she and her girlfriends used to travel there to make out with Black boys to make their fathers angry. It was all very, very grim.

Because I was young and stupid, I came away from the experience convinced not that it was a ghastly enterprise filled with horrible people, but that I was the problem. And that if I’d just had a different voice from day one – one that projected a degree of ambiguous poshness – I’d have escaped that litany of digs and queries about my background. And, more generally, that it’d be so much easier to blend in in places where I otherwise felt like an outsider. Turns out I’m not alone.

Dr Amanda Cole is a sociolinguist at the University of Essex, whose work revolves around accent bias and how it intersects with class, race and gender. She tells me that while Beckham may not have deliberately altered her voice – our accents often change depending on the context in which we are speaking – it is “a fact that people with certain accents are discriminated against or judged more harshly than others”.

Cole’s recent research found that certain groups of people are consistently judged as less intelligent, friendly and trustworthy than others when reading the same sentence aloud. These include people from Essex being rated 11 per cent less intelligent than those from southwest London, and working-class people being thought of as 14 per cent less intelligent than people from the upper middle class.

Beckham, whatever her spicy nickname, was never exactly “posh”, but she was “posh” compared with her bandmates – she famously once said she was embarrassed that her businessman dad used to drive to her local comprehensive school in a Rolls-Royce. Despite that, it does make sense that Beckham’s voice would change – be it consciously or unconsciously – as she entered new social stratospheres of wealth and moguldom.

Cole adds that people shifting their voices or losing their accents reflects the world that we all occupy. “It’s very easy to understand why an individual changes their accent, or feels the need to do that, because they themselves want to get on or they want their children to get on,” she says. “What’s underpinning that, though, is just inequality and prejudice in society. When we see prejudice, it’s no coincidence that it targets certain groups, because those groups are seen as inferior. Accent bias is actually just a window into those prejudices.”

Not that there are any specific guidelines to follow. In truth, working-class people get trapped in a catch-22: lose your accent to avoid being judged, but also be judged for losing it in the first place. Cole points to a raft of recent examples of people in the public eye, with working-class backgrounds, who’ve been mocked or jeered at for speaking in their natural accents. They include TV presenters Alex Scott and Rylan Clark, as well as Labour MP Angela Rayner.

“All these people have been criticised for their accents, and it’s used as a way to make it seem like their voices shouldn’t be heard in those specific settings,” she says. “But at the same time, when working-class people do change their accent, it’s seen as something inauthentic. It’s seen as ingratiating yourself to the higher classes – it seems insincere – or as something deliberate and calculated. So it’s just another way of slapping working-class people down.”

Learning to navigate a class system lined with trap doors is a very working-class experience, and there is something vaguely comforting about even the poshest of Spices encountering that. But it’s also depressing that rather than empathising with her change in voice, a number of onlookers have chosen to mock her instead. Particularly when – if we’re being totally honest – many of us can identify with that feeling of changing ourselves if the alternative is being laughed out of the room.

As for me, I did eventually lose the shame placed on me for my natural accent, even if my years of trying to suppress it have now left me with a jarring soup of a voice that veers between Bristolian, Irish, and Elizabeth Taylor. What didn’t go away, though, is the anger about having felt the need to change it in the first place. As a country rich in accents and cadences, we need to do better.