My grandmother, Ilse Cohn, died on 29 November 1941. No, that’s not quite right. She was murdered – shot by a Nazi execution squad on the edge of a huge burial pit on the outskirts of Kaunas in Lithuania.

Last Sunday, as I opened my copy of the Observer, I found myself staring at the heart-stopping photographs of German Jews in the city of Breslau, now Wrocław in Poland, who had been rounded up to await deportation. Breslau was my grandmother’s home town.

All but one of the photos, which have only recently come to light, were taken on the very same day that she was arrested, in the grounds of the Schiesswerder, an entertainment venue and beer garden, which is where she was taken after her arrest.

Was my grandmother in one of those photographs? Was it possible, more than 80 years after the event, that the grandmother I never knew was pictured in the paper where I worked for more than a decade, just days before her death? I have consulted the experts, but so far they have drawn a blank.

I am sure, nonetheless, that she is there somewhere, even if the photographer, thought to have been an architect and amateur photographer called Albert Hadda, seems to have missed her. Hardly surprising: more than 1,000 people – men, women and children – were arrested in Breslau that day, and they were all herded to the Schiesswerder, where they were held for four days in freezing temperatures before being bundled onto trains and shipped 750 kilometres east to Kaunas.

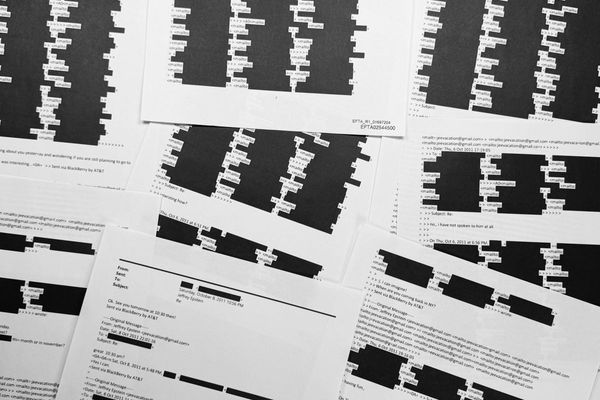

I have in my possession a chilling, detailed account of Ilse’s arrest, written in 1946 by her non-Jewish sister-in-law and sent to my mother, who had fled to Britain as a refugee just before the outbreak of the second world war. It was from this account, nearly five years after her mother’s brutal death, that she finally learned of her fate.

“My dear child [my mother was 25 when the letter was written], I deliberately did not tell you any details about your dear Mutti because I did not want you to lose all hope that you might see her again. Now you will hear everything, although it is very difficult for me to give you such painful news.

“Mutti was picked up by two Gestapo men on the morning of 21 November. The bell rang, she opened the door, still in her dressing gown, and then she had to get dressed in their presence ... They were ‘kind’ enough to tell her to put on some warm clothes and to take extra clothes in her rucksack. She also took her eiderdown … They told her to take enough food with her for four days and they took her to the Schiesswerder … Herr Metzner, the chemist, who had rented out your dining room, immediately called on me to tell me the terrible news.

“I quickly looked for some warm clothes (Ilse hadn’t taken many warm things), made up a parcel, put some food in it as well, and took it to Schiesswerder. But despite my urgent requests, no one was allowed to get near; the fence was guarded by soldiers with fixed bayonets.

“We tried to find out what was going to happen to all these people, and where they were going to be sent, but we couldn’t find out anything. Once they had gone, there was never any sign of life from any of these unfortunate people again.

“However cruel it was that your mother had to be included in this first transport, at least she and the others who were with her were unaware that they were being taken to their deaths. The people who were taken later knew more or less what fate awaited them.”

Ilse was among the very first German Jews to be deported and murdered. The Nazis’ determination to make all of Germany’s towns and cities Judenrein (Jew-free) had entered a new phase following the invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, when vast new territories opened up to which German Jews could be deported.

Only after the Wannsee “final solution” conference of Nazi leaders in January 1942 did the extermination camps – Auschwitz, Sobibor, Treblinka and the rest – become the main tools for the planned elimination of all Europe’s Jews. Until then, between mid-1941 and early 1942, an estimated 2 million Jews were killed in what is sometimes called the “Holocaust by bullets”. The gas chambers became the preferred method of mass murder only once the Nazis realised bullets alone just weren’t efficient enough for dealing with the huge numbers involved.

Four days after her arrest, my grandmother was put on a train at the start of a gruelling three-day journey to Kaunas. On their arrival, she and her fellow deportees were marched 6 miles out of town to a hill-top prison known as the Ninth Fort. There, within hours, they were all shot.

The SS colonel who ordered their deaths, Karl Jäger, kept a meticulous daily tally of his unit’s achievements: over a six-month period, they shot a total of 137,346 people. In a report written in December 1941, he gave the numbers of those who died with Ilse on 29 November 1941 at the Ninth Fort: “693 Jewish men, 1,155 Jewish women, 152 Jewish children, evacuated from Vienna and Breslau.”