A maverick, unpredictable loose canon, Paul Westerberg is one of the most lauded songwriters of his generation. With his band The Replacements, his genius for writing rowdy yet often melancholic tunes was matched only by the band's reputation for booze-soaked performances, where the 'Mats – as their fans called them – would stumble drunk through shows, occasionally abandoning the stage completely. In 2004, as he prepared to release his sixth solo album, Folker, he sat down with Classic Rock for an interview.

His hair is still solidly dark. He sits in his favourite chair, flicking through the sports pages, checking the baseball results. His son’s visits are more regular now, almost regimented; from every other day to every day, now that they almost see the end when they won’t be able to spend their afternoons like this any more. His son brings his grandson to see him, too – three generations sitting there in one room. He looks at his son and he feels regret, thinks he could have been a better father, been around more, drank less. His son tells him to forget it; he means it, too, he doesn’t want this to end with regrets. His son is writing a song about him, and wants him to still be around to hear it, wants it finished before his father is gone for good.

“That song [‘My Dad’] is like a photo in a way, like a snapshot of my dad towards the end,” says Paul Westerberg, on the phone from his home in Minneapolis. “There’s a photo on the new album with me on his knee as a kid, and that’s the first photo you see when you open it up. That’s him in his prime. It’s strange how small his life became, you know: the TV, the bible, the newspaper. While he was ill, towards the end, I was there with him every other day, and then every day. I’d sit and hold his hand. The song was written before he died. I was hoping he might hear it, but he didn’t. He passed in November.”

It’s been more than a decade since Paul Westerberg released his debut solo album, 14 Songs. His then label, Sire/Reprise, knew the value of his past, and hedged their bets on his future with a cover sticker on it that read: ‘The voice and vision of The Replacements’. And, just in case you’d missed the point, ‘Replacements’ was about three times the size of the rest of the type.

It wasn’t an empty boast; The Replacements’ dishevelled splendour leaned heavily on Westerberg’s sometime cock-eyed songwriting genius. With him often irascible and drunk, their live show was a firecracker waiting to go off. Not that it always did. They could explode wildly or implode gracelessly, it didn’t seem to matter a damn to them. Producer Scott Litt (R.E.M., Nirvana, Patti Smith) tells a story in the liner notes of The Replacements’ posthumous best-of collection, All For Nothing, that illustrates their reckless, utterly careless, self-destructive bent.

Setting off to meet them in a darkened conference room in the Warner Bros. office in New York, Litt was literally tackled by all four of the band as soon as he walked in. They’d smeared the walls and themselves in black ink from carbon paper they’d found in the street. Litt concludes: “As a result of my mugging in that conference room, my knee still hurts when it rains.”

It is indicative of the ardour and adoration The Replacements inspired in others that Litt agreed to work with them a little over a year later. Even if he did wince every time there was a downpour.

When the inevitable split finally came, the band left Westerberg – initially (even though the credits on All Shook Down read more like a solo album than a band record) he was wary of going out on his own.

“I didn’t feel comfortable at first,” Westerberg says. “But the demise of the ’Mats was long and slow, so that when it happened it was fine. “I remember that we were in Copenhagen, and Tommy [Stinson, bassist] saw this poster for one of our shows, and it was billed as ‘Paul Westerberg and The Replacements’. He tore it down and went, ‘Fuck this’. I think that was it for him. “It was odd, I really felt butterflies going up there on stage on my own for the first time.”

Westerberg’s latest solo album, Folker (“It basically means I like folk music, I’m comfortable with the genre. I still love rock’n’roll, though. That’ll always be a part of me”), combines his lilting melancholy with equal amounts of cynicism and ribald laughter. He says the album is not quite folk. And it’s not. It sounds like a Paul Westerberg album: arch, emotive and succinct.

Perversely, it opens with a jangling ad called Jingle (Buy It) that sounds like a disdainful poke at consumerism.

“Actually,” Westerberg says, “ I’m still trying to get it used for the Converse campaign. The whole campaign is home-made ads, so I shot half an hour of my feet and my son’s tennis shoes, and they’re pitching that. That song was written to be on TV as a commercial, as a tongue-in-cheek thing. I’ve come to terms with songs being used to sell cars or beer or whatever, so I thought why not come right out and say it.”

The Replacements always were a contrary bunch. Initially they were signed to the Twin/Tone label (they would eventually sign to Sire). Disenfranchised by their deal, they heard a rumour that the label was going to reissue their early albums on CD. So the band – drunk, naturally – convinced the label’s receptionist that they were at the offices to work on remixes, got hold of as many master tapes as they could find, and threw them in the river. They later claimed they were hopeful that another Minneapolis native who lived downstream in a big purple house – Prince – might see them floating past, rescue them, play them, and reconsider the way he worked.

“I heard that Ryko were looking to do a new best-of and looking for some tapes,” Westerberg says today. “Those tapes may or may not be in the river. What can I tell you ? We were boneheads, we had no control and we had no money, so we’d destroy stuff. We weren’t criminal, we were dumb.”

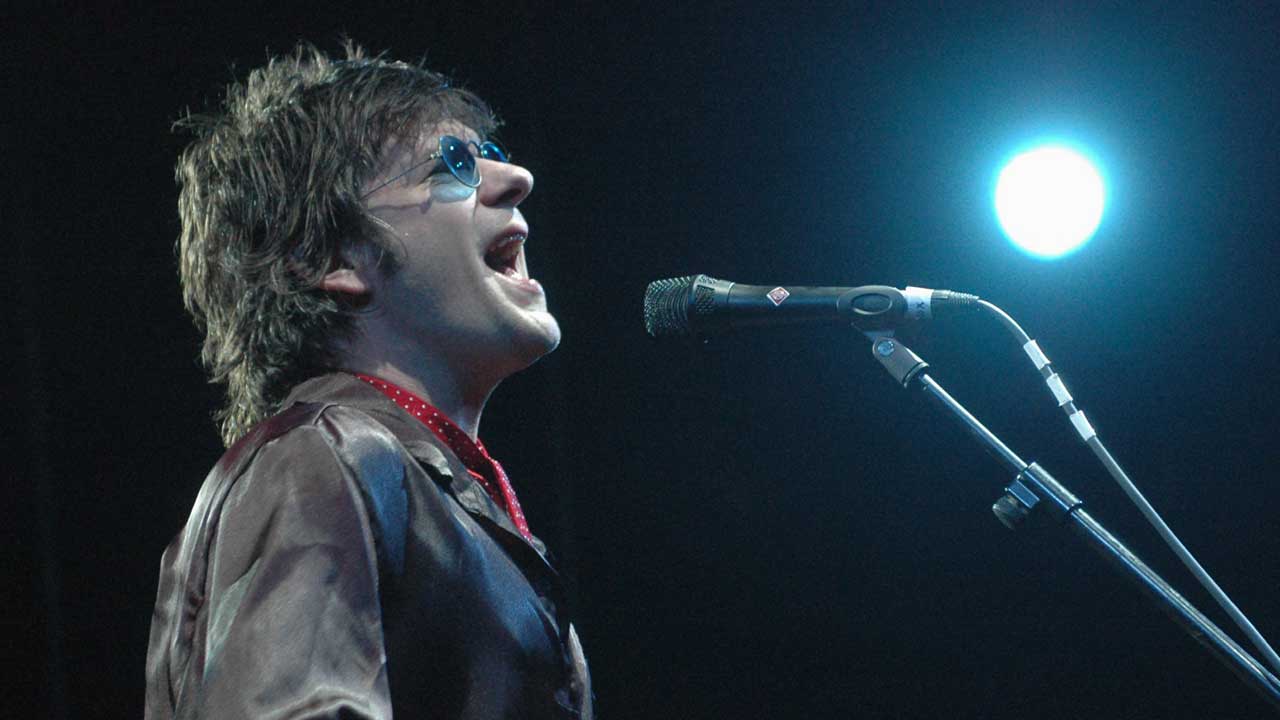

When not making Paul Westerberg albums, he has found time to cultivate his Grandpaboy alter ego. Paint-splattered and with sunglasses that look like cheap Confederate flags, he cuts a troubling figure. In a certain light he looks like the ghoul at the end of The Blair Witch Project might. Distorted and cruel and guaranteed to give children nightmares, Grandpaboy is the more raucous, bellowing extreme of the Paul Westerberg canon. He released his first EP in ’97, and has managed two more albums since: Mono (released as a CD set with his Stereo album) and Dead Man Shake (released concurrently with his Come Feel Me Tremble album in 2003).

“Grandpaboy gave me something that the solo stuff didn’t,” Westerberg explains. “It took the pressure off being Paul for a while. And it fooled people who didn’t know me at all; some people had no idea it was me. I was wondering, ‘Do I have any worth? What happens if I change my name?’”

By the time of his second solo album, 1996’s Eventually, Westerberg felt as though he was running out of options. The 14 Songs album had received good press, and the shows – including a short run of sell out shows in London – got rave live reviews. But it had been three years since its release, and the label, looking at Westerberg’s radio hit with Dyslexic Heart, from the Singles soundtrack, were expecting something more.

“I was aware that I’d worn out my welcome at Warner Brothers,” he says. And I will admit that I tried to write a hit song, you know, something like Love Untold. And I go back now and listen and I still like those songs, I’m not ashamed of them. But I did try to get on the radio.”

To hard-core Westerberg fans it was verging on heresy. Slick production, however, does nothing to dent the songs; especially the touching Good Day that he wrote for his former bandmate Bob Stinson (brother of former Replacements and Guns N’ Roses bassist Tommy), whose ongoing substance abuse had led to him being fired from The Replacements in 1986 and then to his untimely death nine years later.

By the time Westerberg released 1999’s Suicaine Gratifaction, no one was surprised to find that he’d moved to the Capitol label. Courted by label head Gary Gersh (who helped sign Nirvana) and produced with the help of Don Was, Suicaine Gratifaction was a stark and arresting album. This being Paul Westerberg’s story, it simply couldn’t last. There’s a chuckle and a brief, hacking cough.

“Of course, Gersh had gone the day I mastered the record,” Westerberg says. “He called me at the record plant and said he was no longer with the label. I was about to tell him how great I thought the record sounded. That album really felt like the last straw. And all along he’d wanted me to make this raw record, he’d been with me through the entire process, and then it was like: ‘Where’s the single, Paul?’ I think he was warming me up for the A&R men he knew I’d have to deal with when he’d left.”

Stereo followed in 2002, but by then Westerberg had been worn down by the vagaries of the music business, and – as a fully fledged family man – with the idea of touring. Money had come and gone (“I’ve never really worried about money. I’ve had enough to get by. I was a millionaire for one whole day, and then came the manager, the taxman and I bought a house. This was around the 14 Songs album. I signed a deal with Warner Chappell. The money was gone in an afternoon, literally”) and one final festival show was destined to drive him off the road.

“We were at some outdoor show and we were way out of our element,” he says, recalling the shows the band were playing in support of Eventually. “It was full of kids, and I got hit with a can right off the bat. So I turned round to the drummer, Josh Freese [now with the Foo Fighters], and we just played this blues jam for about 20 minutes and then walked off. And I just thought I’ve had it.

“The guy who threw the can actually flew to Minneapolis and apologised to me. All his friends had been badgering him because he threw the can, and he came to me for my forgiveness."

His self-imposed exile from touring ended with a solo club and in-store tour that more or less charted the route The Replacements had taken all those years before. He gave his merchandise guy a video camera and recorded it all, which became the DVD and album Come Feel Me Tremble. The solo shows made Westerberg his first money as a live act ever. With no band to pay, he turned a profit every night (“But, saying that, I don’t want to end up in a position where I have to go out solo just to survive”). However, he has already put a band together for some November shows in America.

“The last time I went out solo I did actually relish the contact with the fans. But it’s odd with some of them – there is a small faction of stalkers. The FBI were looking into some people who wrote cryptic things to me. People think I’m singing directly to them sometimes. I’m here to tell you I’m not.”

While Westerberg celebrated the release of Folker, former Replacements bassist Tommy Stinson released his own album, called Village Gorilla Head. He'd been a member of Guns N’ Roses for years, so you can see why he might have the time to make a record. There were rumours of a Replacements reunion tour for a while, but it turns out that the two most photogenic former members weren’t even on speaking terms any more.

“No, we’re not in touch. We were leaving messages for a while, and now we’re not talking, I guess,” Westerberg says evenly. “He took offence at something, I guess. The line from his camp is that I’m a lot more difficult than Axl. We’re soul brothers – he doesn’t hate me, but I think if we were going to play together then it may have happened by now. Hell, we could be in the same room and they’d have to lead us by the hand to each other. It’s like brotherly love: we’re not friends, but there’s love there.”

Still occasionally beset by both anxiety and depression, Westerberg has undergone periods of counselling, and is currently on medication, a side effect of which makes his eyes sensitive to light, hence the semi-permanent shades which many assumed was a pose – albeit a good one. He has also started to have the odd drink again.

“People are obsessed by that. But I wrote all of my best tunes sober, even if as a band we were drunk. I don’t drink in the day. I go through those Mats [Replacements] songs now, and they were written in the afternoon, when people were at work. There are some moments on there, some stuff’s fuelled by drink, but that’s like guitar solos that I’d put on late at night.

“With the counselling there was a point where I was having some kind of meltdown, and I did think that everyone on the radio sounded like me. Not in a crazed way, but I could hear me in a lot of other artists. So I was telling this to the guy I was seeing, and he thought I was paranoid and out of my mind. He’s sitting there taking notes, and I think he was just writing the word ‘loon’ on his pad.” He cackles loudly.

“Then he went and asked around about me a little bit. When he found out who I was it got better, and we had a relationship from there. And I feel a lot better now. I’ve sort of come around, and it’s anxiety that rears its head more than depression, but I suffer with both. And it’s hard to treat both. I don’t know what it is. Everyday life, I suppose. Before your call I was drinking coffee, and my heart’s pumping and I’m nervous. For no good reason.”

By the time you read this, Folker will have been released and you’ll be able to see how magnificent it is for yourself. Right now, though, Paul Westerberg is sitting at home; he can hear his son out at the back of the house, his wife’s upstairs. Sometimes he thinks about his dad, other times he strums absently at his guitar.

“I’m 45, and I’ve gained a little weight and I don’t give a damn, and I don’t dye my hair any more,” he says before we hang up. “I saw Ron Wood, and [keyboard player] Ian McLagan’s hair is pure white, but Woody’s is jet black and. You’ve got to get a little grey in there. And as soon as you have a kid, that stuffs irrelevant anyway; he’ll love you whatever, so you let go a little bit. I’m getting to be middle-aged here, with a son, and I don’t regret it a bit."