In 2013, as Motörhead geared up to release their 21st album, Aftershock, iconic frontman Lemmy was bestowed with a prestigious Metal Hammer Golden God award. On the eve of the ceremony in London, the 67-year-old looked back on a lifetime on rock’s frontlines.

The old warrior rides into view once more. He’s been here a thousand times before. He’s fought every battle there is to fight. He’s won most of them, lost a handful. His sword is chipped, his armour dented and discoloured, but he doesn’t flag, doesn’t even slow down.

He’s been doing it for so long that all this is second nature to him, even if he’s never forgotten why he started out in the first place. He’s made a lot of friends along the way, and lost a lot too. But he’s never stopped doing it his way, and that's the thing that sets him apart. And if he’s closer to the end of his path than he is the beginning, well, he’s not going to show it.

“I’m surprised I made it this far,” says Lemmy, the battle-hardened warrior in question. “You would be, wouldn’t you? People were giving me 10 minutes to live when I was 30.”

This month, Lemmy finally gets the recognition he deserves. Motörhead are the recipients of the Metal Hammer Golden Gods award, the highest accolade known to man, beast and everything in between. Why? Because pretty much every band you love will have been influenced by them, directly or indirectly.

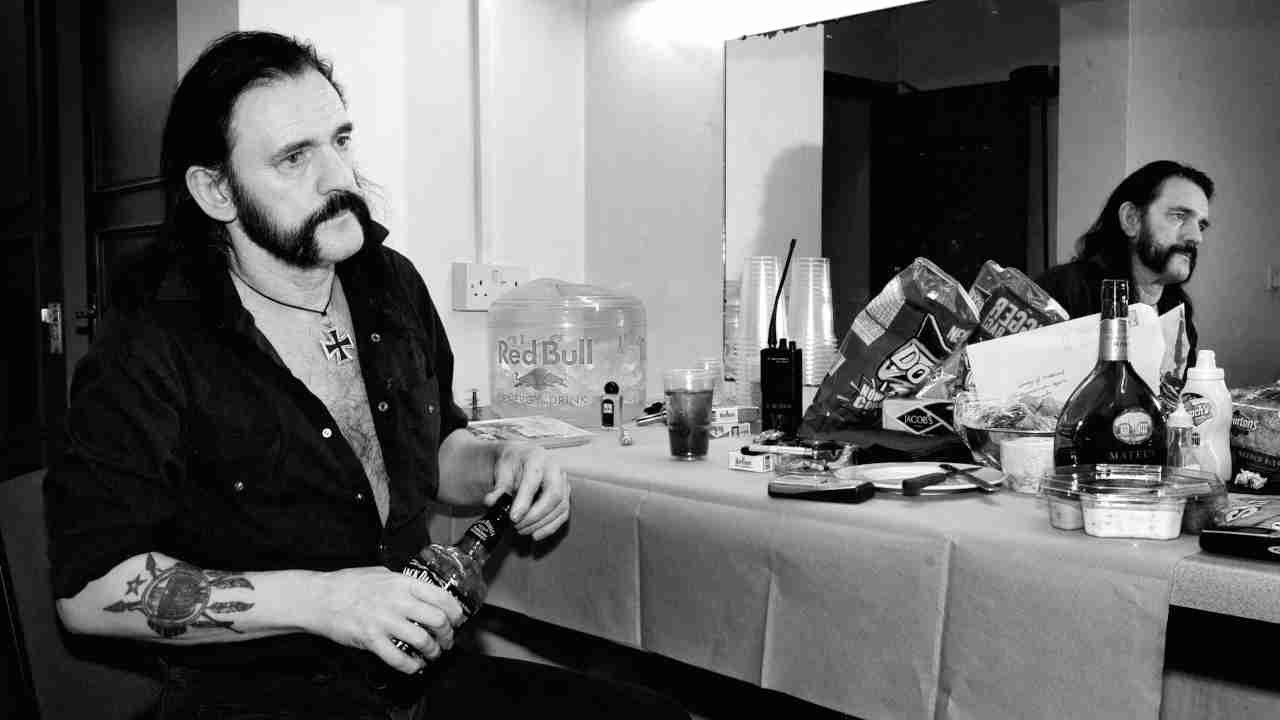

Lemmy is more than just the warty bloke with the cement mixer voice and the bass sound that could flatten a house. He’s the living embodiment of everything they’ve stood for over the past 37 years: the no-bullshit outsider with a tumbler of JD in one hand, a cigarette in the other and an Iron Cross pinned to his lapel.

When Motörhead formed in 1975, there was nothing else like them around. They emerged from West London’s hippy scene, but they certainly weren’t hippies. They made a thunderous noise, but they weren’t Black Sabbath or Led Zeppelin. Thanks to such stone cold classics as Bomber, Overkill, the deathless Ace Of Spades and speed-freak anthem Motörhead itself, they were just about the only band who united the punks and the metal fans.

The band’s first few albums were the gospels of shitkicking rock’n’roll; a whiskey-soaked road map for countless self-respecting hellraisers who followed in their bootsteps. Astonishingly, by the early 80s they were bona fide pop stars – 1981’s stone cold classic live album No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith reached No.1 in the UK charts. “That was alright for about 10 minutes,” he says. “The good bits were everybody going, ‘Yaaaay!’ And the chicks going, ‘Hello there.’ That was excellent.”

They’ve had their rocky patches, sure, and they’ve certainly been taken for granted. But listen to the unstoppable title track from 1986’s Orgasmatron, or 1991’s astonishing spoken word anti-war piece 1916, or the pulverising Born To Lose from 2011’s The Wörld Is Yours. Peaked? Yeah, you go tell that to Lemmy.

You can hear their legacy today in everything from Metallica to Satyricon, Queens Of The Stone Age to the Melvins – any band who doesn’t give a fuck what you think about them, basically. In that room, on the night of the Golden Gods awards, it’ll be the ultimate family gathering: there won’t be anyone there who doesn’t have a trace of Motörhead’s DNA in their own.

And is he looking forward to it? Of course he isn’t. This is Lemmy. He’s just as unimpressed as you’d hope at the thought of an award ceremony.

“I’ve got used to them, ’cos I live in Hollywood and they’re all over the place,” he says. “A lot of it’s political. When we got the Grammy in 2004, it was definitely a mercy fuck, ’cos we hadn’t had one for so long. I don’t really give a shit about the people who organise awards ceremonies. The fans’ appreciation means more to me.”

He pauses, and then this great warrior comes as close as he ever comes to compromise. “But it’s nice, you know. Nice to be recognised.”

Lemmy is 67, which means he’s the coolest pensioner you’ll ever meet. He’s a man of many moods: fearsome, friendly, grizzled, obstreperous, ornery, old-fashioned and, occasionally, a right old bastard. You get the feeling he’s always been like that, all the way through the 37 years he’s spent leading Motörhead, the five years he spent before that as bassist and sometime vocalist in acid-soaked psyche rock overlords Hawkwind, all the way back to his time in long-lost 60s outfits the Rocking Vickers, Sam Gopal and Opal Butterfly.

Today, he sounds different. He’s as politely brusque as ever, but his weary rasp carries the weight of 67 years of the hardest kind of living. Just as some people are born differently, some people grow older differently, and Lemmy ticks both boxes. Ask him if he had any heroes as a kid, and he bats the idea away. “I didn’t really have any. I was just running around, having a good time. Most of my heroes were horses.”

Horses?

“Yeah,” he says impatiently. “I worked at a riding school, pretending to teach people how to ride. Horses are the greatest animals in the world. They’ve got a great sense of humour. Dogs are good, but they’ve got no sense of humour. A dog will just do what you tell it. A horse’ll stand on your foot and take the weight off its other three feet. And they fucking weigh a lot. You’re punching it in the ribs and it doesn’t even feel that. Then it’ll turn around and smile at you.”

He ended up running a farm that belonged to his family. He rode tractors, cut the hay, raised stallions. “Then rock’n’roll raised its pustule-ridden head and off I went,” he says, and grins.

“I joined Hawkwind through a complete fucking lie. The bass player never showed up for a show. Dave [Brock, Hawkwind mainman] said, ‘Who plays bass?’ And somebody pointed to me and said, ‘He does.’ I thought, ‘You cunt.’ I’d never picked up a bass in my life.”

Hawkwind taught him two things. That people who take acid and people who take speed don’t mix. And that he was a stubborn bastard.

“Being a stubborn bastard has always worked for me,” he says. “You keep your integrity.”

It’s an approach that has kept him going over the years – Motörhead are a byword for pure, undiluted single-mindedness, whether that be musical, attitudinal or chemical. But it’s counted against them at times. Things might have been easier if Lemmy had played the game a bit more at various points.

“Occasionally it fits together, but mostly it doesn’t,” he says. “When you walk into a record company and say, ‘Why aren’t there any adverts out there, why aren’t you selling more of our albums?’, or when you say, ‘I’m not having this sleeve’ and then throw it out of the window, they really don’t like it. We got dropped a lot.”

But that’s the point…

“Ah, but they think they know everything. And that you’re just some oik from the country, and without them you’d be nothing. But that’s where they’re going now. There’ll be no record companies in 10 years.”

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

“I dunno yet. The jury’s still out. We’ll have to wait and see, won’t we.”

These days, Lemmy lives in Los Angeles. In a town built on bullshit, he’s an honest-to-goodness anomaly: a figure from another time and place entirely. He doesn’t go out so much these days, the time he’s served in rock’n’roll slowly but inexorably catching up on him. “My legs are fucked and I can’t walk a long distance,” he says, and it’s moments like this that you realise he’s not a young man any more.

“When you’re young, you feel indestructible,” he says. “But then things creep in. I don’t worry about the future. I got sick recently… but you can’t be worried when you wake up in hospital in restraints because it took five of them to put me in bed. Because I wanted to go home.”

There had been rumours circulating that he’d been unwell, but it was chalked up to a lifelong diet of Jack Daniel’s and amphetamines.

“I got a defibrillator put in,” he says, referring to a kind of pacemaker. “I felt very weak for ages. And they found out my heart was only pumping 15 per cent of what it should.”

We’re no doctors, but that sounds bad.

“Heh heh heh! That’s death, you know. I went in for the defibrillator, but it got complicated, so I had to stay in there for a couple of weeks. It was supposed to be a one day thing…”

How are you feeling now?

“Better. Me and Slash joke about them. He’s got one too.”

Have you ever come close to dying before?

“I suppose when I got diabetes 10 years ago. I collapsed in a coma. I just went to sleep, and that was it. It’s a good thing my girlfriend found me. I would’ve laid dead on the floor.”

From the outside, it seems you’ve had a charmed life, health-wise.

“It’s been pretty good,” he says. “I was emergency christened, ’cos they wanted to put a name on the headstone. After that it’s all gravy.”

Have you toned down your lifestyle? Have you eased back on the booze or the speed?

“I drink a little bit. Everything else is out. I stopped smoking.”

How are you finding that?

“Easy. I stopped smoking in one day. I was coughing and I thought, ‘I’ve had enough of this’, so I just put it out.”

You’ve known a lot of people who aren’t with us any more. Who’s the one you miss the most?

“Würzel,” he says without hesitation.

Würzel – or Michael Burston to his parents – was Motörhead’s guitarist and Lemmy’s partner in crime for many years. He left the band in 1995. In 2011, he died of heart failure. When Motörhead played Sonisphere 24 hours after his death, Lemmy looked and sounded like he’d drowned his grief in several bottles of Jack Daniel’s.

“We were calling each other and texting each other a bit,” says Lemmy, sadly. “He was really down. But he became this raging alcoholic, which was a terrible thing. I watched it all the way through from beginning to end. I dunno…”

Have Würzel’s death and your own health issues made you think about your mortality?

“You can think about dying if you like, but it doesn’t fucking matter. You’re going to die anyway.”

Does it scare you?

“It’s pointless being scared of something that’s inevitable. It depends on how you go, I suppose. There are several unpleasant ways to die, but once you’ve gone, it's OK.”

Do you think there’s anything after?

“I dunno. The light at the end of the tunnel is probably an oncoming train.”

Does it make you think about important stuff?

“It does a bit, yeah.”

And what is the important stuff?

“Important?” He lets out a croaky laugh. “Not dying.”

One of Lemmy’s big bugbears is that people still think he and his band are stupid, even after all these years. “You still get people coming up going, ‘Hey man, I love Ace Of Spades. Are you gonna make another album soon?’,” he grumbles, even though he knows it’s them and not him who are the dumb ones.

He’s also astute enough to know that this isn’t going to last forever. Throw the question of retirement at him, and he doesn’t duck it.

“I may retire from touring one day,” he says. “But I’ll never retire from being in the studio and putting albums out. You don’t have to walk good to do that.”

Motörhead have finished a new album, their 21st, called Aftershock. By his own yardstick, it’s already a success.

“If we play it when it’s finished, it’s a success. I’ve been playing the rough mixes for a week, and ain’t sick of it, so that’s a good sign.”

After all this time, you can’t help wondering what Lemmy’s got to show for it. He’s given rock’n’roll and heavy metal an incalculable amount, but what have rock’n’roll and heavy metal given Lemmy?

“I’ve not got a big circle of friends, but I don’t want one. I’m not rich, but I won’t die broke.”

Has it all been worth it?

“Yeah, it’s been worth it. When you’re playing to 100,000 people, all shouting your name, that’s worth it. When people write to you, saying, ‘You’ve got me through a suicidal patch’, it's worth it.”

This Golden Gods isn’t done yet. Far from it. Not while there are still more battles to be fought.

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 246