Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

I distinctly remember the time my friend and I purchased our first “sexy” books. We were giddy and giggly as we browsed the extensive selection of Mills & Boon in WH Smith, two university students regressing to our 13-year-old selves in an instant. There were so many genres within the smorgasbord of erotica laid out before us – were we into sexy historical fiction, or sexy medical fiction? Sexy rich men who were misunderstood royals, or sexy rich men who were misunderstood CEOs? Sexy stable boys getting down and dirty with duchesses, or sexy barristers lusting after legal secretaries (and, if so, would a gavel be involved at any point in proceedings?)? Decisions, decisions!

In the end, we grabbed one apiece at random – mine featured a sheikh of a made-up Gulf nation, my mate’s the heir to a Greek shipping fortune – and cringed with embarrassment as we avoided eye contact with the cashier during purchase, these being the days before self-checkout. We shoved them deep in our tote bags, our cheeks flame-red as we scuttled out of the shop. The only thing worth this abject mortification was the tantalising promise of self-exploration that lay ahead; though the excursion had ostensibly started as a joke, we were both curiously quiet on the walk home, keen to disappear into our respective bedrooms and get speed-reading under the covers.

Times have changed since that first furtive encounter in my late teens – at least as far as sales go. Purchases of print books classified as romance and erotica have more than doubled in the US, leaping from 18 million in 2020 to more than 39 million in 2023, reports The Guardian. UK sales of romance and saga fiction have risen by 110 per cent within the same time frame.

Anyone who remembers being told in their scant sex-ed classes at school that men were gagging for it all the time while women had to be somehow “persuaded” into bed might be surprised by this surge in erotic interest from the latter. I’m not.

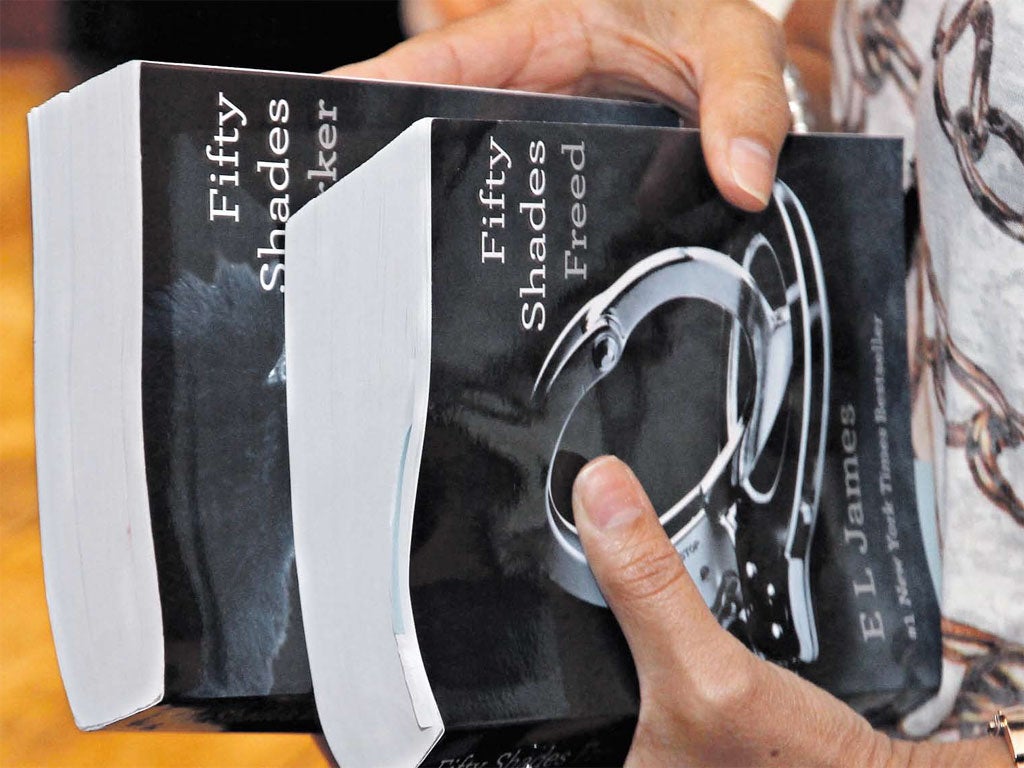

Women have long been into, ahem, stimulating literature, from Lady Chatterley’s Lover and bodice rippers to Jackie Collins and Jilly Cooper; the notion is far from new. But there’s been a tangible shift in terms of shame – or lack thereof – over the last decade or so. It started in earnest with the phenomenon that was the self-published Fifty Shades trilogy back in 2011, when Christian Grey and his “red room” sparked a viral sensation, opening millions of women up to the idea that they might not be so vanilla as all that.

Mainstream, widespread conversations were finally being had about female pleasure, out there in the open. In 2019, Lisa Taddeo’s non-fiction book Three Women, detailing the complexities of female sexual and emotional desire, became a bestseller in the UK and US; it’s now been adapted into a television series starring Betty Gilpin and Shailene Woodley. Netflix’s steamy faux-period drama Bridgerton, based on the book series of the same name, is one of the streaming service’s most-watched shows – and we all know why, even if people don’t care to say it out loud. (I will – women with great hair and makeup wearing immaculate gowns getting seduced in the backs of carriages by handsome gentlemen? It’s full-blown lady porn.)

Then there’s the rise of romantic and just plain horny novels that have driven BookTok into a frenzy and helped drive up sales of the genre. Whatever your particular bent, there’s an outlet: neuroscientist Ali Hazelwood pens smutty love stories revolving around women in Stem and academia; Sarah J Maas specialises in, for want of a better term, “fairy porn”. Emily Henry’s classic “friends to lovers” and “enemies to lovers” romcoms, beloved by millennial and Gen Z women, have sold more than 4 million copies.

“The reason that romance novels have been so denigrated is because it was the one genre where it was OK to talk about female pleasure, and that makes it not art for some reason,” she told The Independent, branding the genre “innately progressive”. “In literary fiction, you can write about people having bad, gross, creepy sex or sad sex,” she said. “But you can’t write about good sex with an emotional connection without people being like, ‘That is drivel.’ I feel like it’s a long con that has been going on since before the Victorian era to just convince women that everything about them is a little bit shameful.”

The change is long overdue. There’s always been a huge mismatch in terms of what popular culture would have us believe and what men and women actually experience when it comes to sex, to the detriment of all. Constant jokes about women pretending to “have a headache” as an excuse to get out of marital duties have pervaded for decades; comedy shows and male stand-ups have perpetuated the stereotype that wanting sex and masturbating were strictly male pursuits – while avoiding them was the preserve of women. But has this ever really reflected the reality of our respective sex drives?

Not according to the science. Testosterone – the hormone associated with a high sex drive – peaks in males at 18, and then very gradually decreases up until around the age of 40. Females, meanwhile, often see an increase in libido in their late twenties and throughout their thirties, even as our fertility is declining (possibly the body’s last-ditch “Hail Mary” attempt at getting us to make a baby). According to one British study, men experience a dip in libido between the ages of 35 and 44, while women experience their biggest dip between 55 and 64.

It’s a long con that has been going on since before the Victorian era to just convince women that everything about them is a little bit shameful— Emily Henry

My thirty to fortysomething peers and I will sometimes talk about it with each other in dimly lit bars, the embarrassment all but dissipated now we’re older if not wiser – “it” being the fact that the tables in many cases have firmly turned. Women are now the ones “gagging for it” in heterosexual relationships, the ones buying lingerie, lighting fancy candles and blocking out time in the diary just to try to get their partner between the sheets. The recipients rather than the givers of the “I’m just too tired” excuses.

Couple this with the elephant in the room – the gender disparity when it comes to orgasming – and you have an environment in which erotic fiction was destined to flourish. Even for those of us lucky enough to be getting some, half of 18-35-year-old women say they have trouble reaching the big O with a partner, while 55 per cent of men versus just 4 per cent of women say they usually climax during a one-night stand. In general, there’s an orgasm “gap” of around 30 per cent between heterosexual couples, according to sexologist Dr Karen Gurney’s book Mind the Gap.

Then there’s the fact that modern dating culture, reducing us to stats, swipes and algorithms on various apps, has all but killed the notion of true romance and courtship. Dates are like joyless job interviews conducted under duress, in which compatibility is determined as clinically and efficiently as possible in the race to find a suitable partner. Under such circumstances, of course sisters are doing for themselves. Instead of questions about career goals over lukewarm beers, we can dive into tales of simmering, sultry looks across the boardroom; yearning hands brushing one another on the dancefloor; gazes brimming with barely contained passion locked over the operating table.

Despite lingering taboos, women are very much into sex. We may not be forever shouting about it from the rooftops, we may not joke about w***ing at every available opportunity, and we may not have a standing subscription to Pornhub. But give us a good book and our imaginations… well, that’s another story entirely.