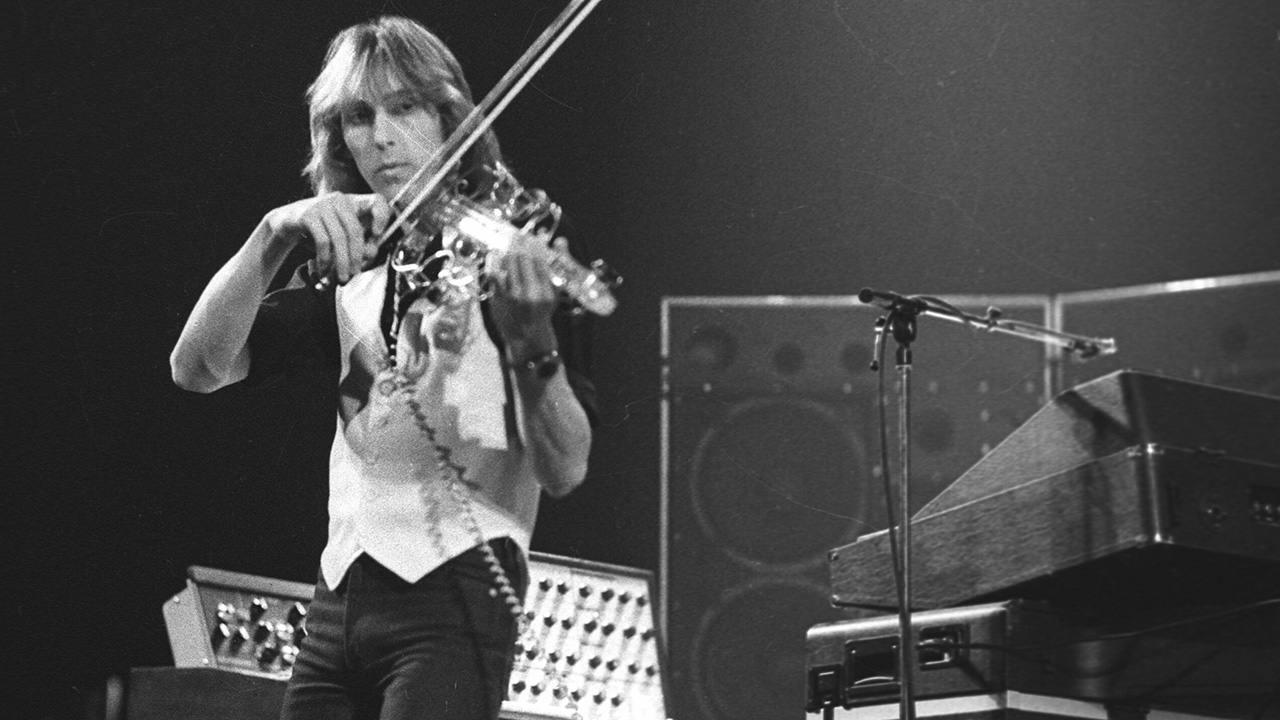

Six months after opening for Curved Air, Eddie Jobson found himself drafted into the band, kickstarting a career that’s seen him ricochet through Roxy Music, Jethro Tull and his own UK, cutting a path uniquely his own. In 2010 Jobson told Prog the story so far.

By his own admission, Eddie Jobson is a details-orientated kind of bloke, and always has been. As a 16-year-old, with a picture of Curved Air on his bedroom wall, he’d dissect Daryl Way’s violin parts, listening to the albums time and again in order to get every note exactly right. Exactly right.

Like every kid who’s ever played along to the albums of their favourite band, he harboured thoughts of what it’d be like to actually be on a stage with his heroes. But unlike nearly every other kid, Jobson did just that.

He’d perfected Daryl’s signature solo piece, Vivaldi – and not just the brief version that appears on their 1971 debut Air Conditioning, but the live version which often extended into a rigorous 10-minute virtuoso performance. Jobson had it all under his fingers and would pull off the solo note for note as a member of Fat Grapple, the Newcastle-based band that acted as support whenever Curved Air came north.

“We were opening for them at Redcar Jazz Club,” Jobson recalls, “and the band were still driving up to the gig from London. So I asked their roadies if I could play Daryl’s violin in the soundcheck. I got up onstage and played Vivaldi.” Ten minutes later, a slightly gobsmacked Curved Air crew had the levels they needed and Eddie was as pleased as punch to have gotten that close to his idols.

Yet he was about to get much closer than he’d bargained for. “When the band arrived from London they caught wind about me playing in the soundcheck and wanted to meet me in their dressing room. I walked in and the whole group were standing there in stage clothes ready to go on.” He still gasps in awe as he recounts the tale.

“These were my heroes, remember, and everybody was right there in this little room in front of me. And there I was, 16 years old, with Daryl Way handing me his violin and saying, ‘I hear you play Vivaldi.’ So with the band standing two or three feet in front of me I played it.

“They started to laugh, though, because I was also playing the echo parts – I’d not realised they were a special effect, and so I’d learnt to play all the repeated notes myself – which made it even harder, I suppose!”

One night Frank Zappa grabbed me and said, ‘I want you onstage tonight!’ And that was it

Six months later, after both Way and Francis Monkman quit Curved Air, the remaining members asked themselves where they might find a violin and keyboard virtuoso. Who else were they going to call? An unintended consequence of Jobson’s almost obsessive attention to detail had just paid off.

Woody Allen reckoned that 80 per cent of success is just turning up. By that measure alone, Jobson can be said to have been extremely successful indeed. After Curved Air, in 1973 he famously took over Brian Eno’s stage-left spot in Roxy Music. For three years he soaked up the pop star lifestyle; but he claims that his upbringing – helping his dad run a theatre – enabled him to stay grounded.

“I was able to deal with the contrasts of being a teen star in Roxy – being mobbed by screaming girls at gigs, and then two hours later, back in London at my apartment by myself looking for food in the fridge – because I just viewed it as theatre. Music-making was my true artistic side. Being on stage wasn’t me; it was just theatre.”

Above the noise of the screaming girls, his musicality came through loud and clear to Frank Zappa, who saw Jobson playing on an incongruous bill which had Roxy Music opening for him. After Roxy’s tour finished in Los Angeles in 1976, Zappa sent his private plane to whisk Jobson to Canada.

“I went on tour with Frank just as a kind of guest – not playing – just to go round and hang out backstage at the arenas,” he recalls. “Before the concerts, Frank and this saxophone player called Norma Bell and myself would just play these little three-part harmony things that Frank had written. We just did it in the afternoon every day for a few days.

“Every night they’d walk onstage and I’d stand at the side and watch the show. Then one night, Frank grabbed me by the arm and said, ‘I want you onstage tonight!’ And that was it. He pulled me on the stage in front of 15,000 people and I had to do pretty much the whole set, just from what I’d picked up observing the previous couple of days.” Once again, Jobson’s attention to detail had paid off.

However, it’s his work in UK that holds a special place in the heart of many a prog rock fan. Having failed to persuade Robert Fripp to reform King Crimson, and an abortive attempt at a trio with Rick Wakeman, former Crimson members Bill Bruford and John Wetton called guitarist Allan Holdsworth and Jobson, and the band was born in a blaze of glory in 1978. Yet the competing factions within the group couldn’t be contained; and by 1979, Wetton and Jobson were left to recruit Jobson’s old Mothers Of Invention side-kick, drummer Terry Bozzio, to replace an exiting Bruford.

Trey Gunn – who’d later become a member of King Crimson and work with Jobson as part of the UKZ project – vividly remembers seeing UK supporting Jethro Tull in 1979 at the Municipal Auditorium at San Antonio, Texas. “There’s some stuff they played where John and Terry were wailing, and Eddie’s just all over it.

“When I started working with Eddie in UKZ we revisited some of the old UK numbers when we played live in 2009. That stuff was definitely more harmonically sophisticated than some of the Crimson material. It was pretty hard, and hearing some of the keyboard parts I thought, ‘Man, can that guy still play this stuff?’ But Eddie was just great. There wasn’t any rest for him, and he was always going from one thing to the next, playing some crazy shit!

“In The Dead Of Night worked fantastically well. It was a really exciting piece of music to play. The Only Thing She Needs – fucking hard, man. There’s some really tricky shit in there and Eddie really had to pull out the chops!”

I always much preferred the controlled environment of being in a studio… you can focus on the details. That’s where the real art is

After UK’s dissolution in 1980, Jobson next turned up as a member of Jethro Tull. “What had started out with me helping Ian Anderson on a solo project escalated in my joining Tull for an album (A, 1980) and touring with them until 1981.” Was he in danger of becoming something of a burnt-out case at that point? “I’ve always enjoyed the details of things more than the big, loud, unsophisticated gestures, which is what being on the road is all about.

“It all gets very loud and it’s hard to control the details – to even play the violin in tune. I just reached a point where I wanted to create new things. It was the turn of another decade, and those affect me greatly. Going from the 70s to the 80s felt like quite a leap. It felt like a pivotal moments when things were really going to change, and I wanted to be on that edge with the technology and the movement of music in general, trying to play a role in the development of playing music for the next decade. That has always been a motivating factor as a musician – trying to figure out what music is about, where it’s going, and my place within that.

“I’d already begun working on The Green Album [Jobson’s first solo record, released in 1983] when I started touring with Tull, and I wanted to get back to to figuring out who I was in the 1980s. It took me another two years to finish the album.”

The hi-tech gloss coating of The Green Album reflected Jobson’s passion for developing his already prodigious technique alongside his grasp of the available technology. In theory he was positioned to embark upon a frontline career as a solo artist signed to a major label. Once again, however, bucked expectations by stepping away from the cycle of album and promotion, preferring instead to veer off into writing film and TV scores.

“I always much preferred the controlled environment of being in a studio, because that’s where you can focus on the details. That’s where the real art is for me. It’s that fine critical listening stage where you’re really focused on things, listening on a whole other level, almost.”

2007 saw him form UKZ, an extension of UK but with a darker, metallic edge, echoing his admiration for Trent Reznor’s Nine Inch Nails. Along with Trey Gunn, UKZ consisted of singer Aaron Lippert (who’d previously re-recorded Wetton’s vocals after a failed UK reunion in the late 90s became Jobson solo project Legacy), Austrian guitarist Alex Machacek and German drummer Marco Minnemann.

With its personnel spread across all points of the compass and the music being compiled remotely via file sharing, Jobson had created his Virtual Virtuoso supergroup. “I ended up with a band of citizens from five different countries who had never met!” he laughs. “It was about trying to use the technology and trying to do something contemporary.”

Having been absent from the concert stage for nearly 27 years, his enthusiasm for live performance has been revived. Though keen to embrace the new music showcased by UKZ, he understands that promoters with an eye on the bottom line probably prefer him to be playing his greatest hits. “That’s why I’ve put together the U-Z project,” he says.

“It’s basically a covers band, performing what I consider some of the best progressive rock – particularly the things that I either wrote, or maybe something that influenced me. It’s usually things connected with my career or the careers of the people who I end up getting to guest with the project.”

One surprising recruit to the U-Z party was John Wetton. With neither of them getting any younger, they agreed to put aside their differences to celebrate their shared past. “I brought John into the project in Poland in November 2009, and we did three shows there. It was the closest thing to a UK reunion in 30 years, so obviously we played the classic UK tracks and I also chose to play a lot of the classic King Crimson tracks that John sang on.”

We’re all on this bumpy ride… somehow or other, quality and integrity are going to matter for something

Now distributing his music via his own subscription-only website, Jobson is sanguine about operating as an outsider. “I don’t even consider myself to be in the industry! As of 1980 I started managing myself – being my own agent, getting my own record deals, eventually forming my own record company, and now with the advent of the internet, YouTube and all of the other ways you have of getting this stuff out. I’ve just continued, for something getting on for 30 years to try and be completely independent of the big five media conglomerates and all of the middlemen.”

How will it all work out? Well, as ever, the devil is in the detail, and Jobson is paying close attention just as he’s always done. “We’re all on this bumpy ride right now trying to figure how it’s all going to play out.

“What I do believe however, is that – somehow or other – quality and integrity are going to matter for something. I’m just a guy from the north of England who’s trying to make some music. That’s all I’m trying to do. That’s all I’ve ever tried to do for the last 40 years.”