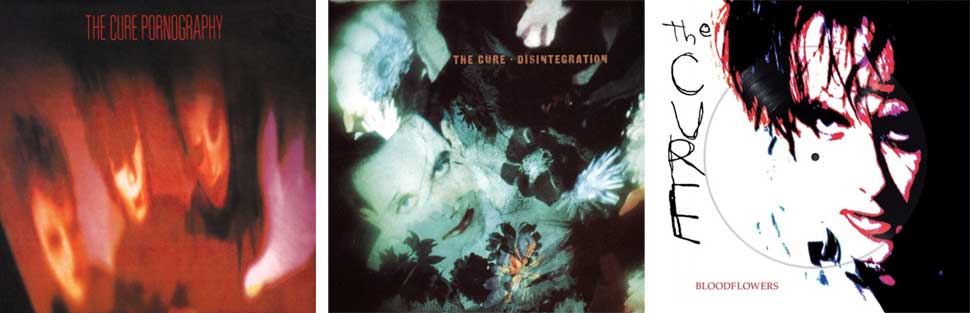

In 1982, The Cure released Pornography – one of the bleakest records probably ever recorded, its tone set by the opening lyric ‘It doesn’t matter if we all die…’, while seven short years later (and this is after all the gleeful pop hits, remember) Disintegration would hit the shelves, its mood sombre and dark, and with a lyrical introduction (‘I think it’s dark and it looks like rain…’) to match its counterpart at the other end of the decade.

Almost 20 years on from Pornography, in 2000, Robert Smith sat down to think about where he wanted his band to go next. The last few records had been predominately upbeat affairs, and for some peculiar reason, he got to thinking about The Cure of the 1980s.

Thankfully, it wasn’t, but it took a Smith a foray into his 80s bleak period to figure out where he wanted to go next.

“I listened back to Pornography and Disintegration one particular weekend. I listened to them a couple of times each. I got very drunk. And got to thinking about what makes these records so special? They are always the two records that are brought up by Cure fans as being the ones that seem to symbolise everything they like about The Cure. And for me as well, they are probably the two key albums that define The Cure, so I wanted something to follow that.”

The resulting album was 2000’s Bloodflowers, similar in tone and mood to The Cure’s bleak, atmospheric 80s material. It also became the final chapter in what would become known as The Cure’s Dark Trilogy (Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers). However, this trilogy happened entirely by accident.

While spending that weekend drinking and rediscovering those earlier records, one thing that had never occurred to him before suddenly struck Smith.

“I realised that I did Pornography when I was just turning 20 – well, I was just 21 – and I did Disintegration when I was just turning into a 30-year-old man,” he says by way of explanation. “I was now heading toward my 40th birthday, so I thought I should probably do something that is a third part.

Upon rediscovering his bleak 80s muse, Smith found that both Pornography and Disintegration were (unwittingly) encroaching upon their live shows.

“We spent about nine months going around the world,” recalls Smith. “And we found ourselves playing a lot of the Pornography and Disintegration songs and a lot of the older, heavier stuff – it fitted in more with the mood of Bloodflowers. We hadn’t really done a tour like that for a long time, not since the Disintegration tour where we went on stage and we were playing really heavy sets. I just thought it was really good fun and it was the best tour I’d ever done. I thought this isn’t the end of the group as I’d previously been thinking – I just had to re-find what it was I liked about being in the group.”

Ironic, then, isn’t it that both Pornography and Disintegration were recorded at times when Smith was anything but a happy bunny. As Smith and the others – the line-up then included the perennial Simon Gallup on bass and Smith’s childhood friend Lol Tolhurst on drums and keyboards – have admitted, the Pornography sessions weren’t the most fun time. The band was on the verge of splitting, as Smith admitted to Rolling Stone.

With Phil Thornalley in the producer’s chair, the band set about making their artistic statement, as Smith said in last year’s Pornography reissue, “I wanted to make the ultimate fuck-off record. And then The Cure could stop. Phil was trying to make it too nice… I wanted it to be virtually unbearable. I needed this recording to be our grand statement, and in the course of making it I didn’t much care about anything or anyone else in the world.”

Smith doesn’t have particularly fond memories of that time, but does acknowledge that it’s one of The Cure’s finest hours. Funnily enough, it took the harrowing recording process and subsequent tour to make Smith realise that, contrary to possibly his own expectations, he didn’t want to be tagged as a doom and gloom monger. And that’s when the ideas sprang into his mind for the 80s day-glo material.

He returned to his parents’ home in Sussex, and set about playing around with the idea of a three-minute pop song. When he took a demo of Let’s Go To Bed into his record company, Smith admits that it wasn’t the most successful meeting he’d ever been to.

“They said, ‘You can’t be serious. Your fans are gonna hate it.’ I understood that, but I wanted to get rid of all that. I didn’t want that side of life anymore; I wanted to do something that’s really kind of cheerful. I thought, ‘This isn’t going to work. No one’s ever gonna buy into this. It’s so ludicrous that I’m gonna go from goth idol to pop star in three easy lessons’“.

And that’s exactly what he did. The chirpy pop single took both the US and UK by storm, and many new fans were confused as to what they found when they went exploring their favourite new band’s back catalogue.

Smith, meanwhile, just found it all faintly hilarious. His fanbase had entirely changed almost overnight. “It went from intense, menacing, psychotic goths to people with perfect white teeth. It was a very weird transition, but I enjoyed it. I thought it was really funny.”

“It’s almost like worrying that no-one’s gonna know who you are if you don’t have the same line-up. And it’s always been the case where I have been the most visible person in the band, for most of the time. But Simon [Gallup]’s been there on bass for pretty much all of the time I’ve been in the band apart from two, maybe three years [the period immediately following the Pornography tour] – he’s been the bass player in The Cure for more than 20 years.

"Cure fans know that, but I suppose the media as a whole just thinks it’s me and a bunch of others. I mean Porl, who’s in the band at the moment, has been in the band before – he was in the original band that did demos before we even recorded, so people just come and go. I mean Roger [O’Donnell, keyboards]’s been in the band before – he was in for Disintegration.”

As the time dawned to enter the studio for Disintegration, Smith suddenly became aware that he and his band had become everything he didn’t want to be. They had become a huge stadium rock band.

“It sounds really big-headed, but everyone wanted a piece of me,” Smith told Rolling Stone. “I was fighting against being a pop star, being expected to be larger than life all the time, and it really did my head in.

“I got really depressed, and I started doing drugs again – hallucinogenic drugs. When we were gonna make the album I decided I would be monk-like and not talk to anyone. It was a bit pretentious really, looking back, but I actually wanted an environment that was slightly unpleasant.”

Spotting a theme, anyone?

Finally Disintegration did get made, and it was quite a departure from 1987’s upbeat Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me. But that didn’t stop the upward ascendancy of The Cure – fans latched on as easily to the sombre Pictures Of You, spooky Lullaby or plaintive Lovesong (written by Smith as a wedding present to his wife Mary), as they had to Just Like Heaven or The Love Cats.

Again, they took to the road and despite Smith’s distaste about being a “stadium rock band”, the tour was a resounding success. The new material giving the band a chance to stretch out and enjoy themselves.

“Cure fans feel short-changed if we do anything less than two-and-a-half hours,” said Smith. “We’ve done festivals where we’ve had to come off after 90 minutes and it’s just awful, cos we’re just getting into it.”

After Disintegration, though, “most of the relationships within the band and outside of the band fell apart,” said Smith in 2004. “Calling it Disintegration was kind of tempting fate, and fate retaliated. The family idea of the group really fell apart too after Disintegration. It was the end of the golden period.”

It was also the end of the 1980s.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock presents The 80s.