Einstein’s First Law of Thermodynamics asserts that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. Apparently that applies to high energy, too – in the form of the MC5. Fifty-three years after their third album, High Time, the legendary Detroit rockers have just released the hardly-hoped-for follow-up, Heavy Lifting.

Never mind that everyone in the MC5 had passed away at the time of release (Wayne Kramer, Dennis Thompson and manager John Sinclair all died earlier this year), and that High Time had been heralded as their final album, praised as “one of the most defiant swan songs in rock music”. If any band could subvert the time-space continuum, it’s these cosmic-argonaut Sun Ra collaborators. Who could doubt that they could transubstantiate and release a new MC5 album from beyond the pale?

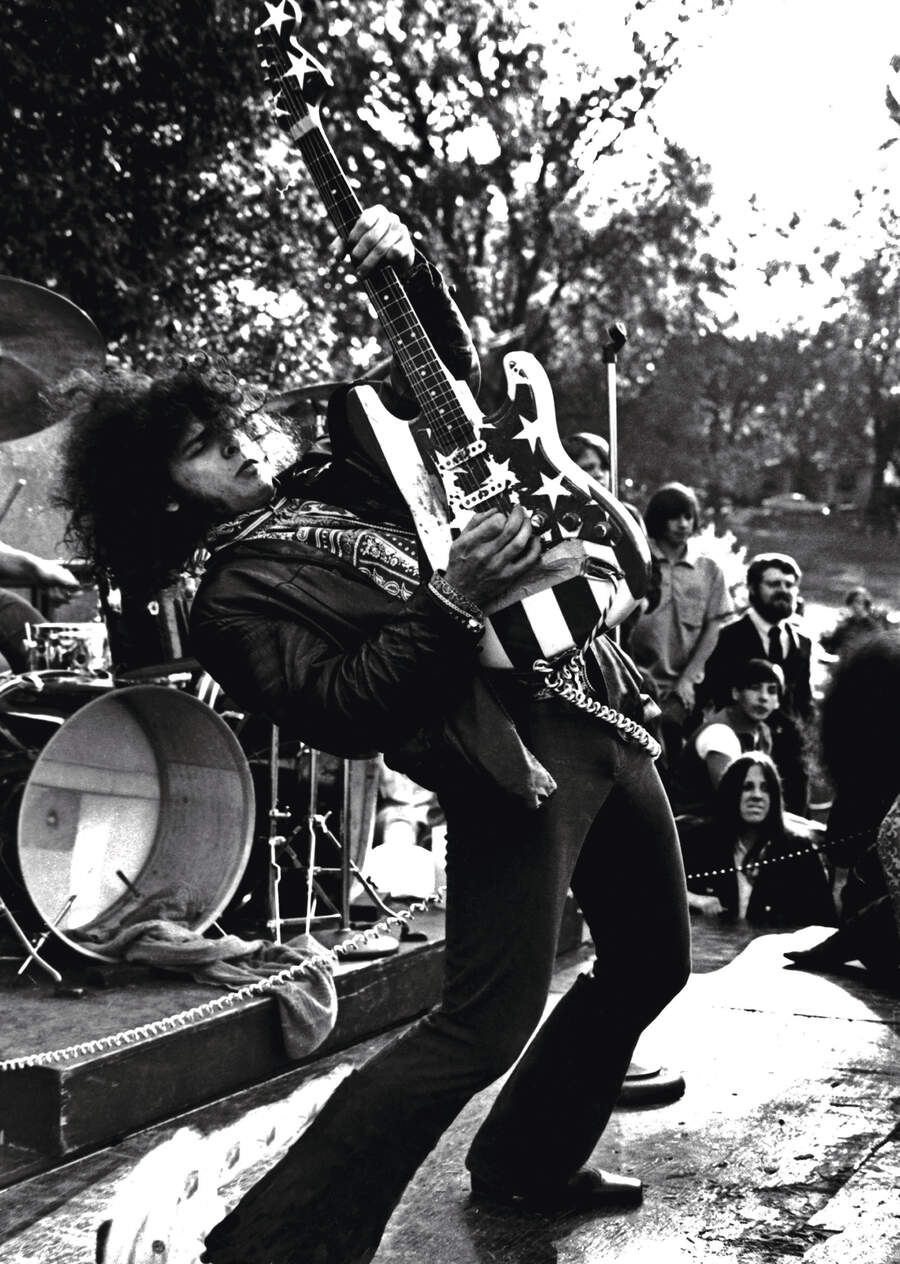

Overlords of rebellious hard-garage/punk rock, in their early days the MC5 set off the first flares of revolution, exacerbated teenage unrest, and legitimised and elevated the counterculture. Anyone who ever saw them – singer Rob Tyner, guitarists Kramer and Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, bassist Michael Davis and drummer Thompson – couldn’t help falling under their spell.

Sonic Youth christened themselves after MC5 guitarist Smith. Lemmy often declared: “Basically, I wanted to be the MC5, playing fast, loud rock’n’roll.” Billy Idol said: “I saw the MC5 at a festival outside of Worthing. I saw the future of rock’n’roll.” Stone Temple Pilots named a song after the band, and Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil said they were “my favourite band ever”. The first call Thayil got about resuming playing after Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell died from suicide was from Kramer. “I think if anyone else had called I would have declined.”

The MC5 started as a cover band, tearing through the stuff they heard on Detroit radio with fierce intensity. Songs by James Brown, Chuck Berry, The Kinks and the Rolling Stones vibrated at a higher frequency when the Motor City Five tackled them. Unlike most other bands that formed during the heady mid-60s, they didn’t just want to start a band after seeing The Beatles on American TV. They had higher goals.

“Sure, we wanted to be a popular rock band, but we did things by principles. I think that’s something that transcends a rock’n’roll band,” Kramer explained, two weeks before his death from pancreatic cancer on February 2, 2024. The MC5, in those more innocent times, believed that music could change the world, their uncompromising blasts of rage and avant-noise the weapons.

“Songs were our organising tools, and they are now,” Kramer continued, last January. “They’re vehicles which we use to share our opinions and our attitudes and whatever we think is possible.”

In those early days, everything seemed possible until it turned out it wasn’t. They outsold The Beatles in their home city of Detroit, were championed by The New York Times and The Village Voice, and made it onto the cover of Rolling Stone before they had even recorded an album. They were signed by Elektra Records; formed the White Panthers, a political party, with manager John Sinclair; they were the only band that performed in a Chicago park in front of the tumultuous 1968 Democratic Convention.

The MC5 were a band that never played by any rules, and in the fall of 1968 they broke the first of many: they recorded a live album as their debut at their hometown stomping grounds, the Grande Ballroom. The band was jittery and over-rehearsed, but, as imperfect as the record was, it managed to capture their cacophonous, soul-imploding live show. It was the sound of a world on fire, the sound of revolution. It was rock’n’roll at its most dangerous.

Kick Out The Jams leaped to No.2 on the local chart, but when a major area retailer refused to carry it because of the F-word in the title song, it kicked off a disastrous spiral. The band took out an ad in two local underground newspapers, reviling the store – and put Elektra’s logo on it. That week the chain pulled all Elektra product off its shelves, and the label dropped the MC5 despite the album having reached an impressive No.30 on the Billboard chart. A scathing review of the album in Rolling Stone by Lester Bangs didn’t help, and America’s biggest concert impresario, Bill Graham, refused to book them after a riot ensued at their Fillmore East gig.

A slight reprieve came when Atlantic Records scooped them up, and they recorded Back In The USA. It was produced by another Rolling Stone critic, Jon Landau (later to become Bruce Springsteen’s manager), as an antidote to the Bangs review. Landau stripped them of their strengths, sacrificing the raw, explosive uncertainty of the first album for a streamlined, cleaned-up presentation. Bookended by two covers – Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti and Chuck Berry’s Back In The USA – the record’s only hints of their earlier polemics was on the sardonic, biting American Ruse and Human Being Lawnmower.

Another blow came in 1969 when manager Sinclair was arrested for possession of marijuana and sentenced to 10 years in a Michigan prison. The band became convinced that he’d used them as a tool for his radical White Panther politics.

The perceived defection of the MC5 (an impression fostered by the spurned Sinclair) alienated much of their early Michigan fan base, the sales of Back In The USA were not what they hoped for (its chart peak was No.137), and their new, New York-based manager, Dee Anthony, stopped returning their calls and eventually sued them for non-payment of commissions.

Things didn’t seem as if they could get much bleaker. But they could. And they did. Drugs entered the picture. Not the mind-expansion of LSD or the hippie amiability of marijuana, but drugs that were psychic erasures, killing disappointment and pain.

“All of a sudden, here were the big, bad, dangerous MC5: a bunch of damn junkies,” Thompson recalled in 2004. They spent much of 1971-72 in London trying to rebuild their career from a European base. They tapped Ronan O’Rahilly, founder of the offshore station Radio Caroline, to manage them. He sent them to an EST-like program for actors to help them get their juju back, booked gigs, and got them ready for their next act.

Their third album, 1971’s High Time, showed they’d finally got the hang of making records. Atlantic staff producer Geoffrey Haslam was less hands-on than Landau, and Smith found his creative stride, writing three songs, including album standout Sister Anne.

While the excitement surrounding the album was at an all-time high, the band’s morale was at an all-time low. In the sleeve-notes for High Time, Dave Marsh stated: “It’s an album about the future by a band that had no future.”

Unfortunately, Marsh turned out to be right. The album would fail to make the charts, Atlantic dropped them, the drug problems increased – heroin had everyone but Tyner in its grasp – and both Thompson and Tyner quit on the eve of their European tour in 1972. Smith and Kramer tried to pull it off themselves with a for-hire bass player, but German fans kept asking where Tyner and Thompson were and forcefully concluded: “You are shit!”

Although the members were barely speaking when the ‘MC2’ returned, they got together for a final show on December 31, 1972, on the small, battered stage of the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, where they had recorded their epoch-defining live debut only four years earlier in front of 1,400 excitable fans. On that last night. there were only about 30 of the faithful in attendance. The show ended with a whimper, as Kramer stormed off stage early in the set, saying: “I can’t do this shit any more.” But it turned out he was wrong.

Over the years, there were failed efforts to reconstitute the band or shanghai the name. Tyner and Smith both died in the 90s, long before their time. Kramer and Davis went to prison. And after the band broke up, revolutions were started and ended, and punk was born, died, and was reborn. But the message of the MC5 endured.

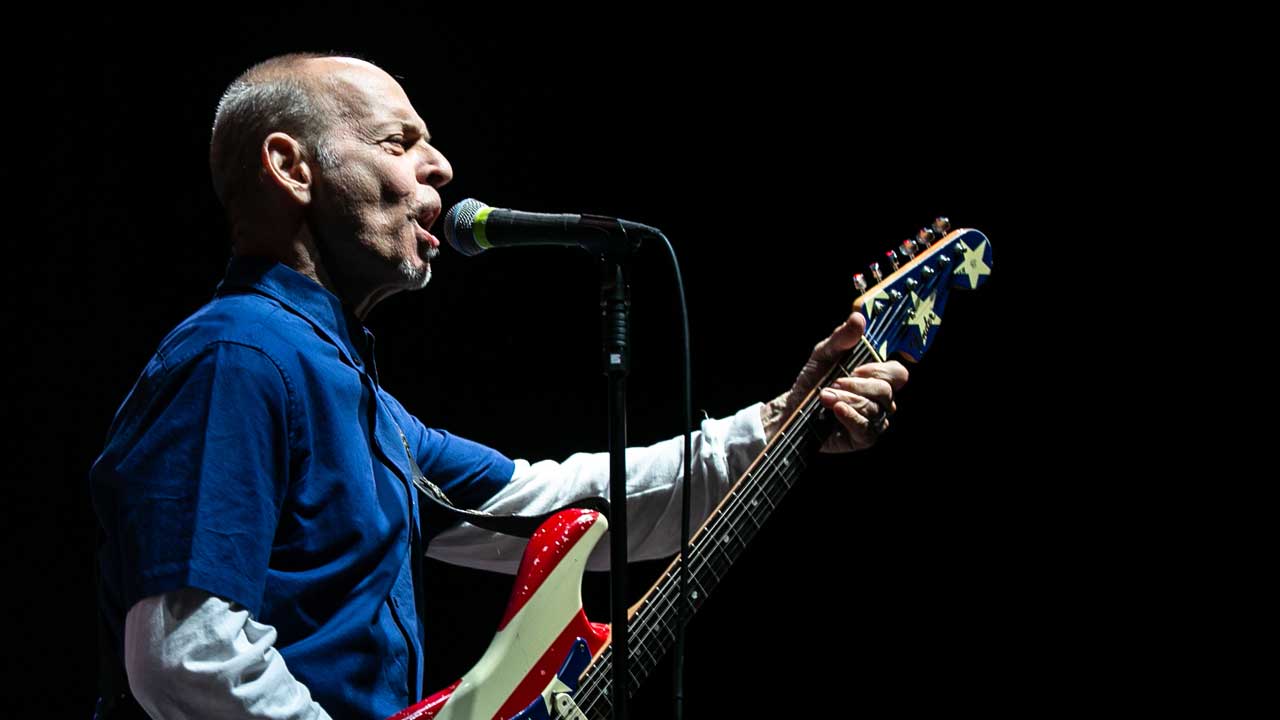

Wayne Kramer acted as the spiritual curator and guardian of the band’s legacy. He attempted to keep the name and the idea of the MC5 alive even after his former bandmates stopped caring. He organised reunion tours: 2003’s DKT tour with former members Davis and Thompson (adding various musicians to fill in for Tyner’s vocals and Smith’s guitar); then 2018’s MC50 tour, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the release of Kick Out The Jams; and 2022’s We Are All MC5. He released 10 solo albums under his own name, but never did he try to release a record under the MC5 rubric.

Until now. And for that, you can credit Bob Ezrin.

After working on Alice Cooper’s Detroit Stories in 2020, Kramer asked producer Ezrin (Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, Kiss), whom he had known since the Cooper band had lived in the Detroit area in 1971, if he could send him some music.

“Of course, I said yes,” Ezrin remembered. “He explained it was going to be the soundtrack for a film that he was writing called Heavy Lifting, about a heist. It didn’t sound like the music for a heist movie. What I really heard in it was a spirit of rebellion, challenging social norms and staring down American values.

"So I told him: ‘This doesn’t sound like a heist movie. It sounds to me like an MC5 record. You ought to think about calling this the MC5 and making a new MC5 album.’ ‘Do you really think we could do that?’ he asked me. ‘You’re asking me?’ I said back. ‘You’re the MC5!’ He argued: ‘But there are almost none of us left any more.’ ‘But there’s you,’ I told him. ‘And in a way, Wayne, we are all MC5.’”

Ezrin isn’t the only one who thinks so.

“I very much related to the phrase ‘We are all MC5’,” says Tom Morello, Rage Against The Machine’s guitarist. “In pretty much every record I’ve made, the rawest, fastest track had the working title ‘MC5’. The idea that music can be transformative in a political and social context pre-existed in folk, but the MC5 electrified it.

“The notion that music makes a difference is a personal experience,” Morello continues. “Music clearly made a huge difference in my life, and I knew the MC5 was telling the truth; NBC News was not, when I was growing up. It was music of the MC5, The Clash and Public Enemy that resonated with me and made me realise that there was a world that was bigger than the small Illinois suburb that I grew up in, and that there were dangerous truths that needed to be revealed.”

When Kramer accepted that he was making the first MC5 album since 1971, he and his collaborator and vocalist, Brad Brooks, kept some of the songs they’d composed and wrote new ones. Kramer and Ezrin contacted musicians who would be excited to play on a new MC5 album. Fans who had become friends, like Morello.

“Morello told me that every day, he sat down and wrote a riff,” said Kramer. “The next day the wheels in my decrepit old brain started turning, and I said: ‘Tom, send me a couple of those riffs, I need some new material.’ That afternoon he sent over a couple of tracks, and I put them into song form, and Brad and I wrote some lyrics for it. It turned into the title track of the album.”

Produced by Ezrin, the album features original drummer Dennis Thompson on two songs, and includes appearances by Slash, Morello, Don Was, Paul McCartney drummer Abe Laboriel Jr., Vernon Reid, Tim McIIrath (Rise Against), William Duvall (Alice In Chains), and M83’s Joe Berry.

It was first titled We Are All MC5, but Kramer felt Heavy Lifting had more meaning.

“It means that this is the really hard work we’re going to do now,” Kramer told me. “It seems as if I’m the curator of the MC5 legacy, and I want to be true to it. I think this record follows in the path the MC5 set out on that last album, High Time. I’m not reinventing the MC5. I can’t go back and try to relive the past. It is what it is, it was what it was, and I have no regrets over any of it. So, what can I do? I can be true to the spirit of the MC5, the values, the ethics.

“We live in a world of symbols. Everything represents something else, and the MC5 represents a kind of uncompromising vision of the future, and that is eternal. If you pull back and give a longer-range view of it, the next generation always has to find their own voice. The MC5 represented a moment in time when it looked like this idea of having a new kind of politics or a new lifestyle would work. And it did for a while. Until it didn’t. It’s time for a new idea.” And a new MC5.

Heavy Lifting is out now October 18 via EarMusic.