When Shanelle Dawson was just four years old, her parents were at the centre of a suburban tragedy when Lyn Dawson suddenly went missing. Her mother’s disappearance would not be classified as murder until 2001, with her father eventually held responsible for the crime in 2022.

Just hours after her mother disappeared from her life, Shanelle’s teenage babysitter, Joanne Curtis (whom she refers to as “J” in her new book) moved into her mother’s bed, wore her mother’s clothes, and (from 1984), her mother’s wedding ring.

“I felt unloved by J,” Dawson writes of her reluctant stepmother, who was her father’s student (at Cromer High School on Sydney’s northern beaches) when they began their relationship. “She didn’t want to be my mother and she certainly wasn’t.” Curtis would divorce Chris Dawson in 1993.

Shanelle did not confront her father about his role in her mother’s death until September 2018, five months after the podcast The Teacher’s Pet, by investigative journalist Hedley Thomas, was launched.

Her younger sister Sherryn, who was just two years old when their mother disappeared, remains loyal to their father. She and Shanelle are now estranged.

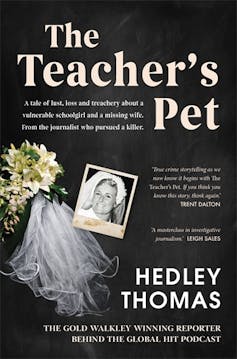

Review: My Mother’s Eyes – Shanelle Dawson with Alley Pascoe (Hachette); The Teacher’s Pet – Hedley Thomas (Pan Macmillan).

In her book, My Mother’s Eyes (written with journalist Alley Pascoe), Shanelle Dawson writes:

In these pages, I’ve capitalised Mum and Mother as a sign of respect. I haven’t done the same for dad and father.

These blunt but powerful words set the tone for a narrative that is compelling, if difficult, reading. Dawson’s journey has been far from easy. She left home at 17 and spent 15 years travelling the world, from the age of 18. She also lost a partner she described as her “soulmate”, when he was found dead in his hammock while travelling without her in Brazil. In 2014, she became a single mother.

Some of her coping mechanisms – like working with psychics to help tie up loose ends – may come across as confronting, or at least strange. She writes, for example, that it was a psychic who first made her realise the truth about her father.

“Please don’t judge me,” she implores in her foreword. She notes that while she has been fortunate in many ways, the book is an opportunity to give her mother a voice, and it is an attempt to exorcise her own trauma.

In many ways, Dawson’s work is about fear. The fear of not being able to remember, fear of never finding her mother’s body, and fear of how crimes of domestic violence continue to be committed. Fear is never straightforward; it is layered – and here it is inseparable from grief.

Dawson explains:

I’ve had psychics tell me that my Mother’s precious body isn’t in one piece anymore. […] I don’t think we’ll get the closure of burying her body whole. That’s a brutal thing to try to come to terms with.

For Dawson, there was also a fear of the truth, bound up with what the conviction of her mother’s murderer would mean. She writes that:

The world sees a monster, but I see my dad. Despite it all, I still love him.

Dawson’s father may not be her “Father”, but he is still a man she has loved for her whole life.

The Teacher’s Pet

Thomas released the first episode of The Teacher’s Pet in May 2018. After 17 episodes, which uncovered new evidence and new witnesses, one trial for murder and another trial for carnal knowledge of a schoolgirl, Chris Dawson is now incarcerated.

Dawson, a former physical education teacher, now 75, was sentenced to 24 years for murder in 2022 with a non-parole period of 18 years, and three years for sexual offences in 2023 with a non-parole period of two years. An appeal against the murder conviction has reportedly been lodged.

True crime podcasts of today owe a great debt to Sarah Koenig’s compelling long-form journalism in 2014’s Serial, with The Teacher’s Pet leading the boom of journalistic true-crime podcasts in Australia. Stories in this format are now ubiquitous. But just as many true-crime books fall short of readers’ expectations, many true-crime podcasts do not meet the demands of discerning listeners. The simple recounting of events is insufficient, especially when it comes to cold cases.

Consumers of true crime want accuracy, attention to detail and compelling theories that can be tested. As human beings, we are instinctively curious. We want answers. In short, we often obsess over cold cases because there is a tantalising feeling that a crime just might be solved.

The motivation of the podcaster is also crucial. As Thomas has said:

I think the best podcasts probably come from a purpose that the storyteller feels. And I think listeners hear that. They hear the authenticity, the righteous indignation, of the storyteller as they’re going through it. You need to be fairly invested.

In Australia, the justice system can be perceived as a wheel that is painstakingly slow to turn, while the media is typically quite chaotic and rushed, driven by punishing reporting deadlines. Yet each is deeply interested in the other – and occasionally keen to exert their power.

For example, Thomas was subpoenaed to give evidence when Dawson was tried for murder. His podcast became unavailable in Australia, and he was unable to cover the trial as if he were just another journalist. The book’s epilogue, titled “The Murder Trial”, is written by journalist and author Matthew Condon, who, with his colleagues, was able to cover the proceedings.

Thomas is acutely aware of how close reporters go to the law’s edges. Almost an entire paragraph in his acknowledgements is dedicated to various lawyers. In pushing back against the legal fraternity, Thomas asserts:

Although they had no insight into the workings of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions in the case, Lyn’s family and many of my legal and police sources were confident Chris Dawson would not have been charged and prosecuted if it were not for The Teacher’s Pet.

This is a big claim, but there is something to be said about a podcast that has attracted nearly 30 million listeners around the world. It has had much more attention than the two coronial inquiries that preceded it – in 2001 and 2003 – into the disappearance of Lyn Dawson. The Teacher’s Pet brought widespread awareness to the case, and an enormous amount of public pressure “for authorities to take action”.

Both inquests found that the woman born Lynette Joy Simms was dead and that a “known person” was responsible for her death, yet neither of these outcomes prompted the laying of criminal charges.

The Teacher’s Pet, as a podcast and now a book, highlights many of the issues that surrounded the formal investigations into Lyn Dawson’s disappearance. Thomas reviews transcripts, conducts new interviews, follows up abandoned leads and finds new evidence. None of this is easy work, and everything is complicated by the passage of time. He writes:

The longer it goes, the harder it is to rely on people’s memories about what they saw or heard. Telephone records, credit card records and CCTV footage – all the information you would normally rely upon in a murder investigation – are all lost or destroyed.

Chillingly, Thomas notes:

For far too long, investigative agencies did not countenance the probability that a significant number of missing person cases were in fact well-concealed homicides.

Readers can experience Thomas’s investigation firsthand in this book. We gain insights into his processes: how he collates information, builds timelines and talks to people connected to the case.

We also see how a sense of urgency saw Thomas collect a box of documents from the 2001 coronial inquest, tear it open in his car and sit parked on the side of a road for hours while he reviewed material looking for precious clues. Disappointments and triumphs are laid bare.

Read more: A criminal record: women and Australian true crime stories

Should we or shouldn’t we?

The nexus between Thomas and Shanelle Dawson is complicated. Dawson is openly appreciative of Thomas’s efforts to find justice for her mother and those who loved her. She likes him “immensely as a person” and has huge “respect for him as a journalist”.

Thomas also uncovered details of the mother who was lost for so long, including footage from ABC television’s Chequerboard, in which an episode on twins included an interview with Chris Dawson and his twin Paul and also featured Lyn Dawson. He returned rare maternal moments to a daughter routinely swept up in what she describes as “familiar grief”.

I was on a panel with Thomas (alongside Felicity Packard and Paul Barclay) for the Canberra Writers Festival in 2019, to discuss True Crime in Australian History. He was confident but unassuming; he did not seem like a brash reporter looking for a quick headline. There was an urgency in his voice.

I could also hear a light layer of exhaustion, reflecting the effect on his work and home life as he worked hard on a case many people thought would forever stay cold. This comes through in his book.

In her book, Shanelle Dawson shouts and swears on the page. Her anger is a testament to her honesty. For example, when she lists some of her father’s explanations for her mother’s disappearance – from “She ran away with a religious leader” through to “She didn’t love us anymore” – Dawson writes: “Bullshit”.

Dawson does not begrudge the recognition Thomas has received for his work. Making a profit from it is something else, and she is uncomfortable that the rights for a miniseries based on Thomas’s podcast have been sold. He has, though, made a difference and helped give a family what they needed most: closure. It is inevitable that someone, somewhere will make money from it.

Dawson also admits umbrage at the title, The Teacher’s Pet, which, she argues, makes the story less about her mother and more about Joanne Curtis. It is easy to side with Dawson, but it is also hard to ignore what Curtis was going through, as she was suddenly elevated from a part-time babysitter to a full-time parent. There are, simply, so many victims in this case.

Yes, we should

Chris Dawson waited six weeks to report his wife missing to police. He waited seven months to claim abandonment, so he could apply for the dissolution of his marriage to Lyn, allowing him to move on and remarry.

For Lyn’s family, their wait was much longer. It was more than 40 years between Lyn’s death and hearing the word “guilty” uttered by a judge in the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

Lyn Dawson’s story – and the thousands like it – deserve our attention. We live in a society that routinely fails to protect its citizens. So many people have fallen through the cracks we all know are there, yet never seem able to fill.

As individuals, we might not feel we can deliver on major structural change, but we can protect the memories of those who have been lost. We can also learn to be more aware of the signs of different types of abuse, including coercive control and physical violence. We can offer support and, perhaps, manage to help one person at a time.

If victims and their families wait decades for justice then, surely, we can give a few hours of our time to engage with these stories, especially if we have access to “good” true crime. Thomas and Dawson both give us books that are worth our time.

The research done by Thomas is meticulous. This is reflected in his book’s end matter, which presents a timeline, a summary of the story’s central figures and a dozen pages of endnotes.

Dawson has chosen to round out her work in a different way. She offers a list of resources for those who need help, and a plea to support crisis centres for women. A portion of her book’s proceeds will go to Women’s Community Shelters, a registered charity working to provide emergency accommodation for homeless women in New South Wales.

The final words in Dawson’s book offer a note of thanks to her Mother:

I’m certain you’ve been with me while I write and possibly even whispered in my ear. I hope I’ve honoured you well and reclaimed our story in the best possible way.

You have, Shanelle. You have.

Rachel Franks does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.