Many contemporary novels adamantly refuse readers a pleasurable reading experience – with clunky prose and a cloying earnestness. But life’s too short for boring books.

Mercifully, Jessica Zhan Mei Yu’s debut novel, But The Girl, is effervescent on the page. It enhances the pleasure of reading with the lively voice of its narrator and its control of narrative pace.

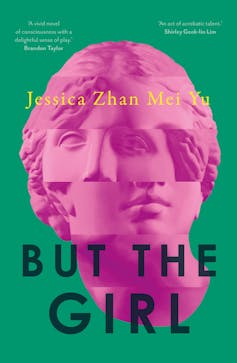

Review: But the Girl – Jessica Zhan Mei Yu (Hamish Hamilton)

The story follows a young writer’s journey as she travels to a writing residency and a postcolonial conference – from Melbourne to London, then on to Arbroath, Scotland. It’s the spring of 2014, in the wake of the tragic disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370.

The narrator is a Chinese-Malaysian-Australian writer and this configuration of identity is foregrounded in the narration. Yu has also written non-fiction about the hyphenation of identity.

However, the cultural significance of this novel is all the more noteworthy because of the author’s imaginative labour, the work’s formal refinement, the care taken with language and pacing.

As the narrator says,

I had a sadomasochistic fascination with English: it hurt me, and it gave me acute pleasure. But I also wanted to be the one to hurt it back, to teach it new tricks, to stand over it, to win its favour, to know it better than it knew me, to mangle it and deform it and remake it into my own image.

Telling it slant

Towards the end of the book, the narrator notes, “I was still the same person who rather than growing upwards found myself moving slantways, downwards, backwards, forwards through life”.

This self-awareness of movement against expectations infuses the book’s unapologetic over-sharing through the chatty, first-person narration with a sense of doubt and uncertainty. It’s a refreshing commitment to self-critique and a refusal of foreclosure.

It also provides a method for writing and for reading this book, the narrator presumably drawing not only from Emily Dickinson’s oft-quoted prescription to “tell it slant”, but also from the “slantwise” expressions of love in Chinese poetry (“in riddles, in rhymes, coyly”).

The story follows the conventional chronological order of a bildungsroman. But this linear unfolding of the plot is frequently undercut and enriched by many kinds of asynchronous movement: a peripheral subject from the former colonies travelling inwards into the heart of empire; a granddaughter moving from fuzziness to clarity in her understanding of familial love; a woman sinking, then ascending towards transformation.

The narrator’s deduction that it’s “better to use the long fingers of memory than the false teeth of speech” encourages readers to examine what is left unsaid. The plot’s linearity is constantly interrupted, as we are offered glimpses into the unnamed, first-person narrator’s past and her current explorations of personhood and power, through witty, interiorised commentary on the configurations of race, gender, class and nationhood.

Read more: In Daisy & Woolf, Michelle Cahill revisits a modernist classic to write a story of her own

Homage to Sylvia Plath

The first sentence of this novel is an homage to Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and a variation of its first sentence:

It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.

Yu’s novel begins by referencing seasonal time, then links to a recognisable tragedy that is itself linked to the narrator’s ethnicity, before finishing off with a declaration of uncertainty as an outsider in a global centre of power.

It was an undecided and hazy spring, the spring that MAS370 disappeared, and I didn’t know what I was doing in London.

In this way, Yu’s opening sentence aims to emulate Plath’s – in syntax, in emotional movement and in tone. It offers readers a way to orient our reading, while firmly establishing time, place and the dispositional vantage point from which the narrator tells the story.

This theme of tribute, disappointment, critique and conversation – of holding Plath close – continues as verse and refrain throughout the novel. It works through intertextual acknowledgement and thematic and literal resonances across art forms. For instance, Clementine, a fellow artist in residence in Scotland, attempts to paint a portrait of the narrator over a portrait of Plath.

It also works through a commentary on Plath’s views of race. The narrator notes Plath’s clichéd description of Esther Greenwood in a “shantung sheath […] In it, she has the ‘odd colour of a Chinaman’.” Elsewhere, she notes Plath’s harmful rendering of racial difference:

together, Esther and Doreen represented two ends of a racially constructed continuum - Esther was a sexless Chinese boy, a ‘good’ minority, and Doreen was an oversexualised Black woman, a ‘bad’ minority. I didn’t describe it in my notes as racist, though it was.

This probing of Plath’s work continues, as the narrator retrospectively charts her growth towards a less hagiographic and more open-eyed apprehension of Plath.

Read more: Sylvia Plath's famous collection Ariel is far darker than she envisaged

Cultural cringe and unstable ‘home’

In her multiple-award-winning novel, Questions Of Travel, Michelle de Kretser writes movingly about the idea of travel (among other things). In Yu’s novel, the narrator’s observations about travel overseas as a non-white Australian, “secretly trying to get away from the huge yawn that was Australia”, are particularly interesting – viewed through the self-deprecating prisms of race, class and gender.

There are the expected responses of shame and cultural cringe at Australia’s provincialism. But they are complicated by the unstable category of “home”, where “home” is not just Australia, but also Malaysia.

Sometimes I wished my parents had immigrated somewhere else; being a child of immigrants always made your birth country feel so random and unnecessary. What if the finger that turned the globe had slipped?

This desire for a different imagined home is, at its heart, a wish to be able to exert agency over one’s life – a wish accentuated when outside one’s “home” country.

This particular positioning of the self also plays out in the way the female Asian body is perceived and possessed. Orchids, unwanted, are received from an unnamed sender. A white male stranger comments on the narrator’s appearance with what she observes as “a mixture of disgust and excitement”, just as he feels the need to whitesplain and mansplain: “Well, I know a thing or two about Asian women.”

Some of the most crisply observed sections of the book are set at the writer’s residency and the postcolonial conference. The narrator, debilitated by self doubt, retorting only in her head at condescension, finds herself in a toxic friendship with the artist Clementine, who, when offering feedback on the narrator’s writing, says,

I don’t know much about the publishing industry but in the art world, I know diversity is kind of like hot now, like it’s the new trend. Which I really stand behind and agree with completely.

The placement of the full-stop here is delicious, highlighting that compensatory pause between passive professional envy and aggressive virtue-signalling.

In her interactions with her various benefactors, the narrator knows she must “simulate delight” and use her “scholarship smile”. She says, “This is the exchange you make: your facial expressions for their funding.”

Yet, despite these privileges of time and money via a Commonwealth scholarship, she is unable to write: “It was the last day of the residency and I really had nothing to show for it and here I was at my desk thinking about writing instead of actually writing.”

Recent novels about the literary world include Michelle de Kretser’s The Life To Come, a novel that brilliantly illuminates the pretensions of academics and writers, and Pola Oloixarac’s Mona, set mainly at an awards ceremony for a literary prize. These novels use their authors’ arsenal of satire to push the interaction between characters to its darkly funny limits.

But The Girl, on the other hand, provides short flashes of exchanges between writers, where the satire feels latent. (Such as when the artists are introducing themselves to each other at the residency in Scotland.)

Perhaps this is in keeping with the narrator’s rendering of the novel form in general as “powerless” and this particular novel’s exacting narration of an attentuated expression of the self.

A love letter

This novel is also ultimately a love letter, especially to the narrator’s formidable Ah Ma, a former maid, now “a matriarch demanding the best of the best for her and for her alone”.

It is also a love letter to the narrator’s parents, Ma and Ikanyu – an exploration of all that is inherited, all that is suffered and all that is owed. As the narrator tells us, “Children are born to be boasted about”.

In her award-winning novel The Eulogy, Jackie Bailey movingly subverts the tropes of the submissive Asian woman and the protective, pushy Asian parent, with an unflinching rendering of family violence.

In Yu’s work too, the clichés of docile Asian womanhood and benignly aspirational Asian parenting are disrupted by an attention to the excoriations and wounds of class inequality and filial piety.

“To hit you is to love you,” the narrator is told after being smacked by her father when she calls her mother “a grouch”. But it is in the rendition of the grandmotherly figure of Ah Ma where But The Girl is at its most moving, as the narrator comes to understand that the expression of love can be comprehended more expansively and less literally, even as it exposes toxic intentions and consequences. As the narrator notes when she remembers her Ah Ma:

it’s hard to explain what I mean when I say she loved me – or as she said when she was especially angry at me – she sayang me.

Jessica Zhang Mei Yu has crafted a finely layered novel, with a vivid interior world and a playful, vivacious prose style. Here is a writer whose sharp observations, embrace of self-critique and crisp voice keep the reader engaged in the imagined world of the novel – and help us see the world anew.

Her work is a timely rumination on the ongoing project of self-construction: tentative, iterative and prone to failure. Yet, ultimately, still holding space for the possibility of joy and transformation.

Roanna Gonsalves does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.