This interview was first published in Total Guitar magazine in November 2020.

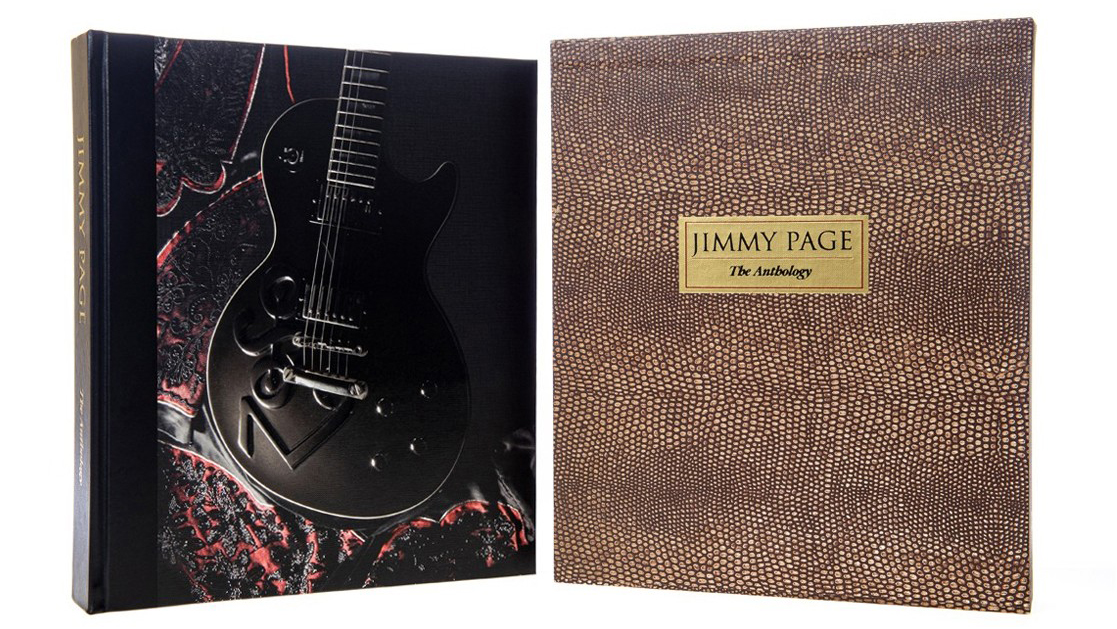

It is an extraordinary story, and as Jimmy Page puts it, quietly but firmly, only he is qualified to tell it. He has a new book published this month, titled simply Jimmy Page: The Anthology. It is what he calls “an autobiography with photographs”, and a “companion volume” to 2010’s Jimmy Page By Jimmy Page.

The focus is on his music and guitars, his artistry and evolution as a player. But there is also the sense, as he explains it, that Page is setting the record straight, in answer to the many unauthorised biographies of himself and his band Led Zeppelin.

“There’s so much mythology about me,” Page says. “In all those other books, because people don’t have all of the information – they make things up. So at least with my book I could be really authoritative, because I was the one who knew what happened. So, let’s do it. Let’s start telling the stories as they really are.”

Speaking to Total Guitar from his home in London, where he has remained since the outset of the global pandemic, Page is in a relaxed mood, happy to talk about every aspect of his life’s work: the groundbreaking music he made, first with The Yardbirds and then with Led Zeppelin; and the tools of his trade, iconic guitars such as the Black Beauty, and the amps and effects with which he explored new sounds.

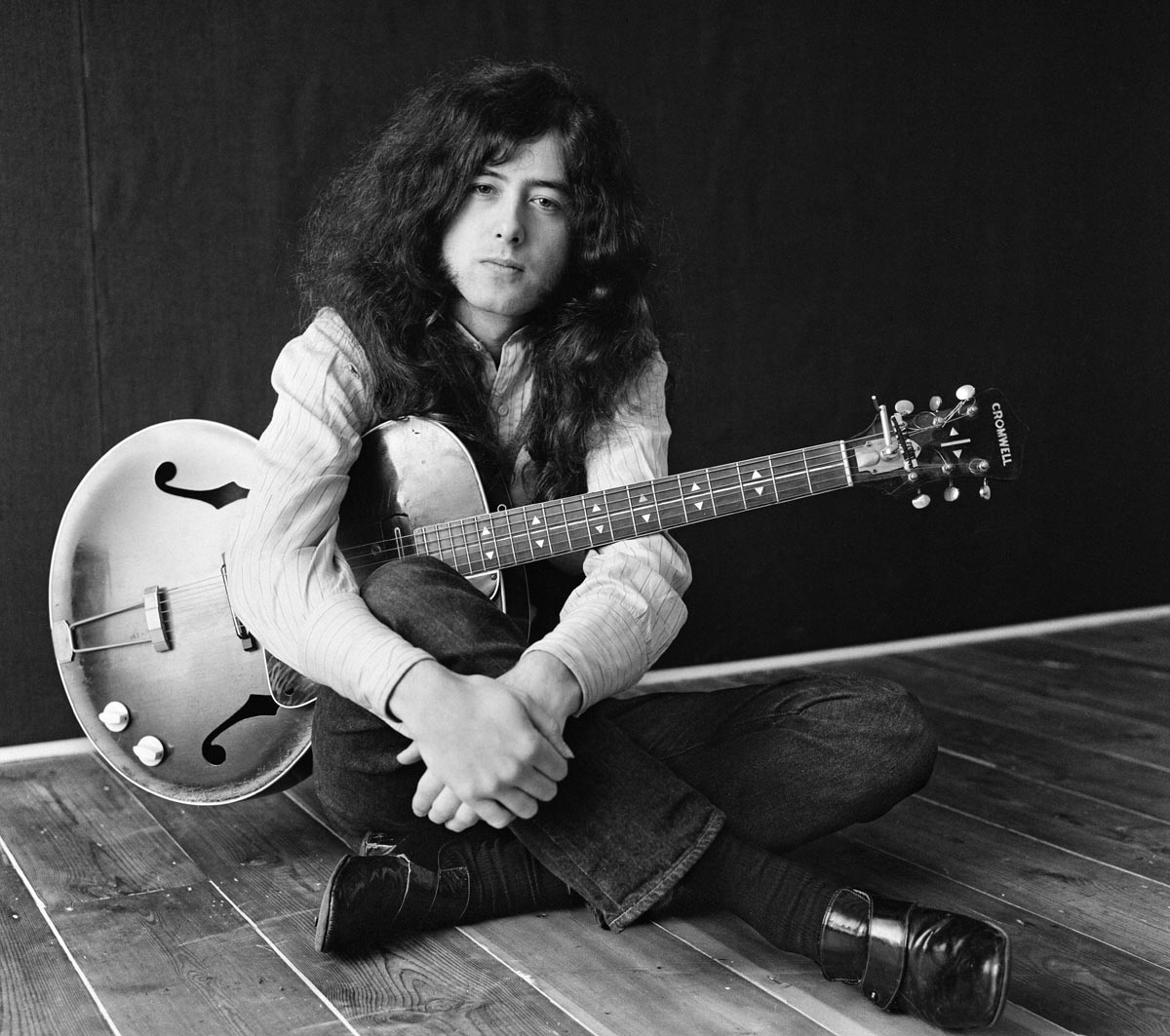

Born on January 9th, 1944 in Heston, Middlesex, James Patrick Page began playing guitar at the age of 12.

Anthology gave me the opportunity to do the detail behind the detail of everything pertaining to my career

Inspired by pioneering rock ’n’ roll guitarists including Scotty Moore and James Burton, he performed in various groups while attending art school, before establishing himself as a session player and producer, working on a number of hit records for major artists, among them the Who, The Kinks, Van Morrison and The Rolling Stones.

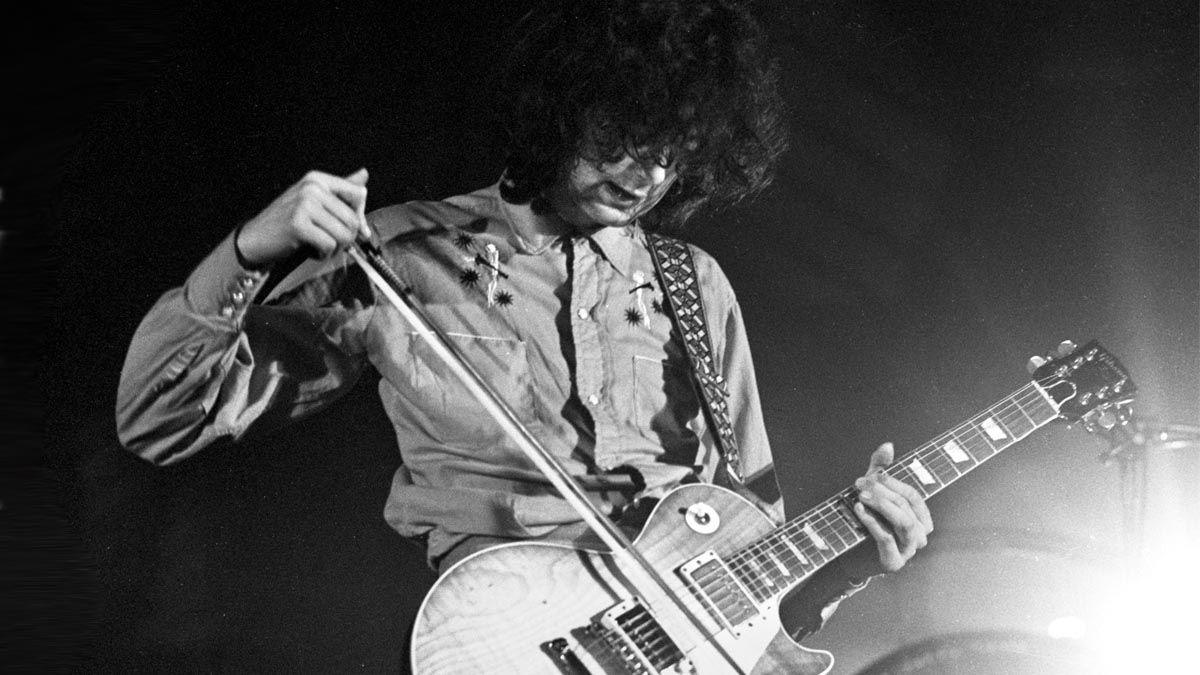

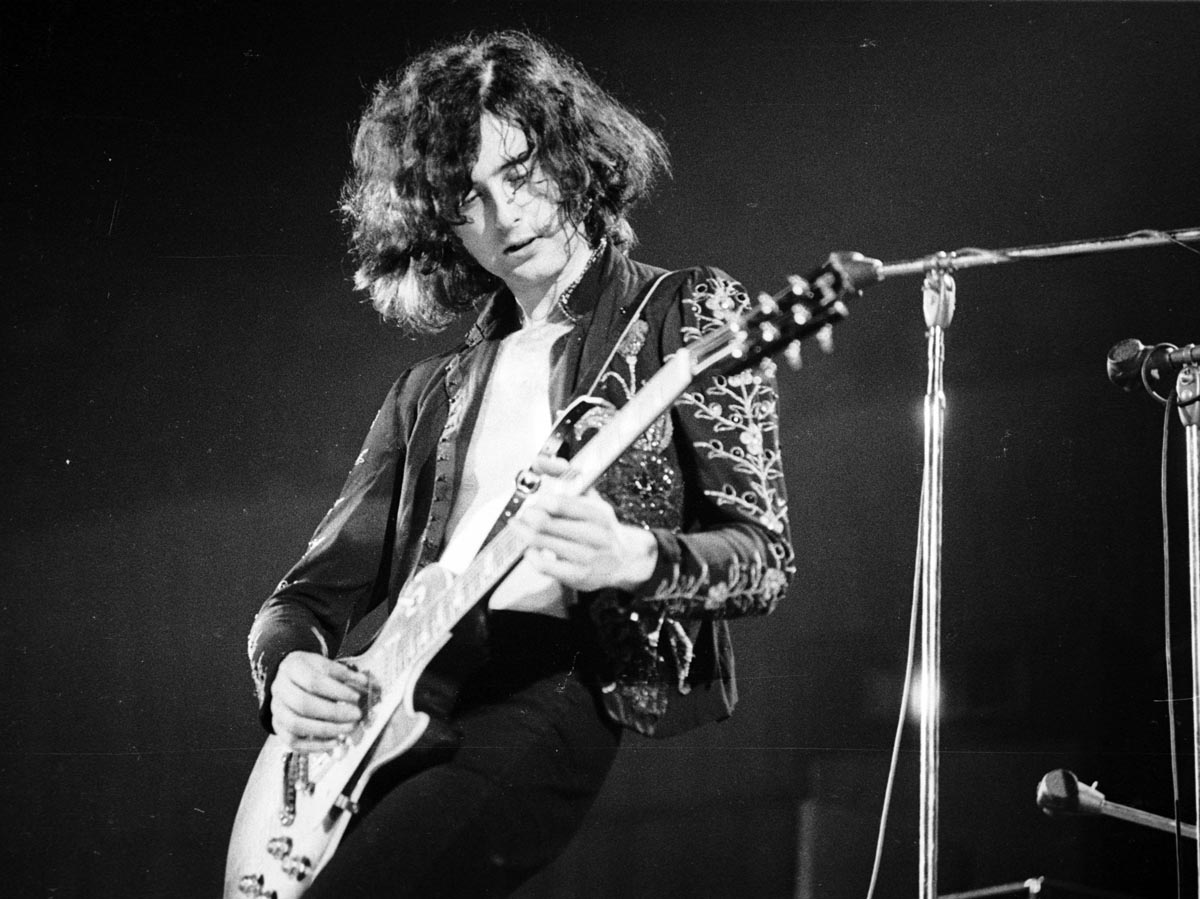

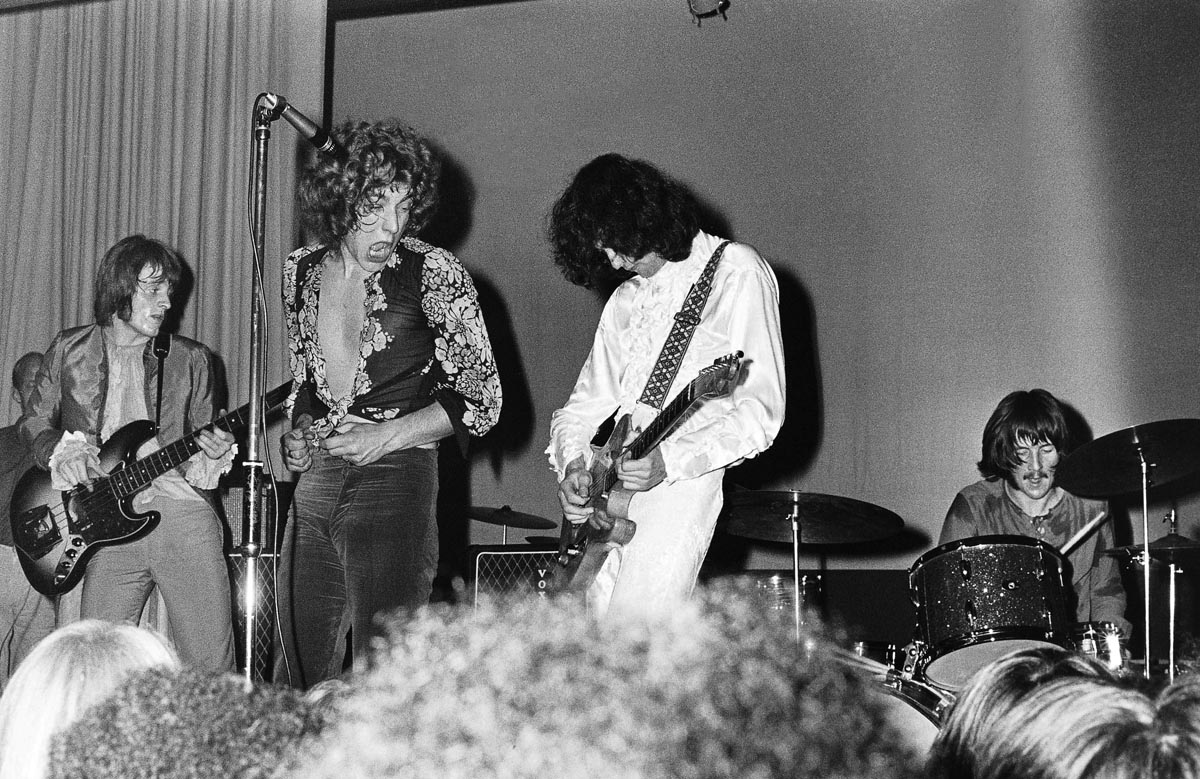

In 1965, Page joined The Yardbirds, one of the leading bands of the British blues-rock explosion – originally as bassist, and later as lead guitarist alongside his friend Jeff Beck.

Following Beck’s departure, Page continued with The Yardbirds until 1968, when, after two members of the band exited, he put a new lineup together with singer Robert Plant, drummer John Bonham and bassist John Paul Jones. Initially billed as The New Yardbirds, the band was subsequently renamed Led Zeppelin.

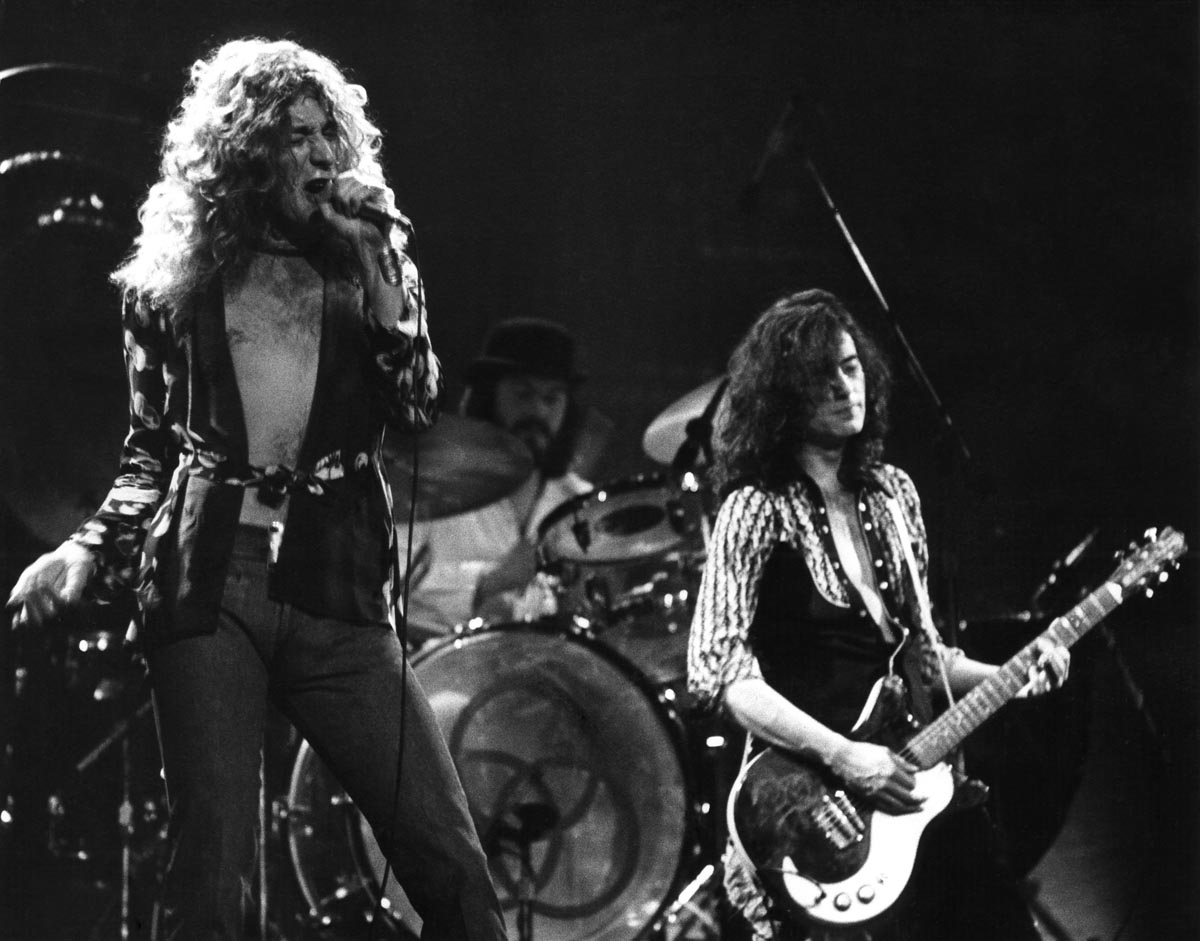

With Page as architect in chief, a series of classic albums, beginning in 1969, defined Led Zeppelin as the dominant hard rock band of the ’70s, with the guitarist’s mastery of blues and folk combining with heavy riffs to achieve a perfect balance, what he called “light and shade”.

The fourth album – officially untitled, but known variously as ‘Led Zeppelin IV’ or ‘Four Symbols’ – was arguably the band’s masterpiece, featuring that most sacred of all rock anthems, Stairway To Heaven. And on stage the band’s prowess, in which improvisation was the hallmark of marathon shows, made them the biggest grossing live act in the world.

Led Zeppelin’s reign ended with the death of John Bonham on September 25th, 1980. In the wake of this tragedy, Page made a soundtrack album for the movie Death Wish II, and formed a supergroup, The Firm, with ex-Free/Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers.

In 1985, there was the first Zeppelin reunion, for Live Aid, with Page, Plant and Jones backed by two drummers, Phil Collins and Tony Thompson. In 1988 there was Outrider, Page’s only solo album to date.

And in the ’90s, another short-lived supergroup, Coverdale-Page, with Whitesnake leader David Coverdale, before Page and Plant reunited, not using the Led Zeppelin name, but performing mostly Zeppelin music on the live album No Quarter.

The duo then made an album of new songs, Walking Into Clarksdale, released in 1998, which still stands as Page’s last album of original material. At the turn of the millennium, Page dug back into his past once again by performing Zeppelin classics with one of America’s finest rock ’n’ roll bands, The Black Crowes.

It was on December 10th, 2007 that Page, Plant, Jones and drummer Jason Bonham, the son of John Bonham, performed as Led Zeppelin for a one-off show at the 02 Arena in London. 20 million people applied for tickets for what was a momentous show, but with Plant unwilling to commit to a full-scale reunion tour, this proved to be Zeppelin’s last stand.

In all the years since, Page has busied himself curating the Zeppelin catalogue – a body of work shaped by his genius as a guitarist, writer, arranger and producer.

What he reveals in Jimmy Page: The Anthology are the secrets of his art, the inner workings of Led Zeppelin, how he chose and modified the guitars with which he created the band’s definitive songs. And in thes Total Guitar interview, he addresses all of that and more...

Jimmy Page: The Anthology is a beautiful book, and so full of detail…

“Yes, it was an interesting thing to do, to put in all the information that you couldn’t put into the first book. Anthology gave me the opportunity to do the detail behind the detail of everything pertaining to my career, whether it was the guitars or the costumes or whatever. To be able to get close-up, personal, and even invasive – so you could see the mechanism of things like the string bender, the circuitry, or the fine detail of the costumes.

And of course, there are a lot of stories behind the guitars... One guitar in particular – your 1960 Gibson Les Paul Black Beauty Custom – has an amazing story.

“The first time I played it, I had such a connection with it. I thought, ‘This is it. After all this searching and going through guitar shops, this is the one.’ I got it before I went to art college, so when I started doing studio work as a session player, that’s the electric that’s used on pretty much all of that work.“

You also played it during Led Zeppelin’s famous concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall in January 1970.

“Yes, at the tail end of it when we did some Eddie Cochran stuff. And after the Albert Hall, I thought I’d take it to the States with me on one of the tours and we’d just do all this rock ’n’ roll stuff at the end, the Eddie Cochran stuff with the Bigsby. So the story is that I take it over there, we’re in Minneapolis going to Montreal, and we arrive in Montreal but the guitar doesn’t. It disappears in Minneapolis. I realised it was lost or stolen.“

And then?

“Gibson, under the circumstances of me having played all the studio work on a Gibson Black Beauty, they made a clone of that, a version of it. That was pretty cool. And I had some extra sort of routing in it, because on the original, where you have the up [position on the selector switch] it is the neck [pickup].

“The middle [position] isn’t the neck and the bridge, it’s actually the bridge and the middle pickup. And then the down position is the bridge. So at no point could you get what you’d get on a Standard, which was the neck and bridge pickup together, so I worked out a way of doing that, and I had that built into that particular model, because I thought, well, crikey, you want to do that, you want any combination that you can get. So that was what I had, a Gibson Black Beauty [replica].“

And you played the replica during Zeppelin’s 2007 show at the O2.

“Yes, that’s the guitar that I played at the O2 when we did For Your Life [from Zeppelin’s 1976 album Presence]. I thought that would be really cool, that thick sound, because it sounded really good. And then after the O2, my guitar that was stolen turns up [in 2015].

“It gets found. Isn’t that interesting? And unless you get the story, you just see a Black Beauty and think, oh that’s the same one he had before. But there’s a whole story about how it gets lost and I didn’t expect it ever to be back in my hands ever again. I thought it was gone.“

John Bonham, with his approach to the drums and the dazzling technique that he had, the overall sound of his drums was unlike anybody that I’d heard before

Are you aware of what happened to it in that time?

“I think it was stolen from the airport and it was stuck under somebody’s bed, somebody who was in some sort of punk band or something, and nobody wanted to rat on him. I think he died, and once he died things became a bit more apparent as to what had happened, and we got it back.“

It’s an incredible story.

“Well, these things don’t reappear, do they? It is a great story insofar as I’m still paying tribute to it, if you like, the one that was lost, even though Gibson made an edition of it. And yeah, then the first one turned up afterwards, and it was amazing, fantastic.“

On the subject of replicas, in 2019, Fender released both Custom Shop and production line recreations of your famed Telecaster. Can you tell us a bit about your original instrument?

“The thing about that is Jeff Beck gave me a Telecaster, one that he played in The Yardbirds for a while, but I was still doing sessions, and he gave me that as a gift. And once I went into The Yardbirds I was playing that Telecaster. Bit by bit I started to customize it. I put some mirrors on it.

I wanted to really make the guitar my own. People had started painting guitars at that point and I thought, well, I’d like to paint mine and really consecrate it

“I wanted to really make the guitar my own. People had started painting guitars at that point and I thought, well, I’d like to paint mine and really consecrate it, so that guitar is absolutely my own. So I went about painting it [with the Dragon artwork] – all that art school training didn’t finally go to waste [laughs]!

“This was a guitar I was using in The Yardbirds, so when Jeff left I had the one with the mirrors and then I painted it. And that painted guitar goes through from The Yardbirds through Led Zeppelin.“

The finish on this Telecaster was damaged, wasn’t it?

“Well, somebody mucked up the painting on it. I needed to repaint it, let’s put it that way. Somebody had sort of vandalised it in my absence. So [restoring] it was always something I wanted to do. I had to take it back to the natural wood.“

And the guitar was renovated for an exhibition of guitars at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019.

“What happened was that the people from the Met came to my house and they had a blueprint floorplan of how they wanted to do the exhibits and they explained that they wanted the original instruments, and I thought, 'Here’s the time to actually [restore] it, because that guitar was going from the Yardbirds to Zeppelin I’, for God’s sake. So this is the time to do it. So I got in touch with Fender.

“I got a graphic artist to help me map it out, so that I could paint by numbers and then build it up. So that was the way I approached it.“

Then, of course, came Fender’s reissues...

“Then the idea was I’d like to do a run of it, and Fender said they were really interested in doing it. Other people were saying, ‘You don’t have to do it with Fender’, but I thought, no, if it’s going to be honest it has to be a Fender thing, they’re going to measure it up and get that neck which is a really unusual neck, all manner of different things about it that needed attention paid to it.“

You were right to go back to Fender, because their Custom Shop is so good at this…

“Oh gosh, yeah. I worked with a guy there called Paul Waller, and he was a dream to work with, such a cool guy. I saw the machinist stamp out the plates that go over the screws that hold the neck to the body of the Telecaster and the Strat. Jesus Christ, it was an amazing place.

“In a factory, I didn’t think that spirit existed anymore, but it jolly well does at Fender. The spirit in there. It’s like they know what they’re making is something that is going to be really loved by somebody.

“Not only that, it’s going to be like their buddy, if you like. And not only that, that combination of the instrument and the musician – that can make people happy. So they’ve got the right attitude. It’s a really noble thing that they’re doing, as opposed to something like making a car part in a factory. It was a great experience.“

I’ve often wondered if my Number One Les Paul had been re-finished when I had it, by Joe Walsh, who sold it to me

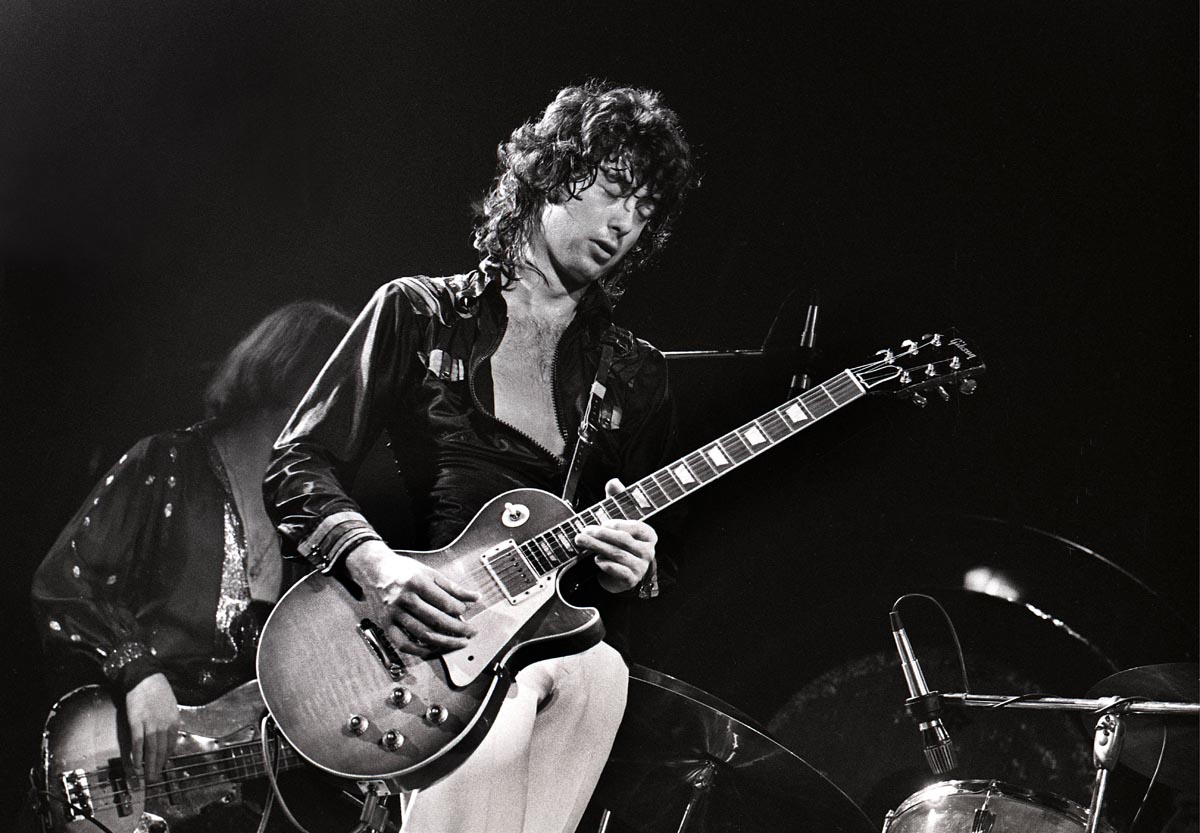

Les Paul ‘Number One’ and ‘Number Two' are your famous sunburst Standards. What are the differences between them in terms of setup, and more than anything how they feel to you when you’re playing them?

“The first one has got quite a shallow neck, and that’s how it was when I had it. I’ve often wondered if it had been re-finished when I had it, by Joe Walsh, who sold it to me – whether he had re-finished it. He had more than one Les Paul at the time and he’d obviously decided to let this one go. But this was the neck that was on it.

“On the other one, they all played differently, they weren’t consistent on the ’50s ones. There’s a definite difference in the feel and the tension between the two of them. I’m not so sure whether the neck is quite so shallow on the Number Two, but it’s not one of those big clunky ones.

“And tonally it’s different as well. However, that’s the one I started to experiment on, so that I could do all various combinations, [coil-tapping] with the push-pull switch.“

I gather you used two 12-strings, the Fender Electric XII and the Vox Phantom XII, on Stairway To Heaven...

“That’s right. The Vox one, I had that in The Yardbirds, so a lot of the stuff in The Yardbirds – Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor and all those things – were done on that. And then I got the Fender one a little later. I think I got that when I came back from America the first time I visited. So basically I had two electric 12-strings, and on Stairway... I wanted to use both of them, so I’d have one [panned] left and one right.

I thought, what’s the guitar, how to do this on stage? And it was just obvious that the doubleneck is the only way I’m going to do it

“There is a slight difference obviously in the sound of them, so that bit in the fanfare that leads into the solo with all the 12s, that’s tracking both the Vox and the Fender. There’s a photograph in the book that shows the setup: the two 12-strings and the six-string solo.“

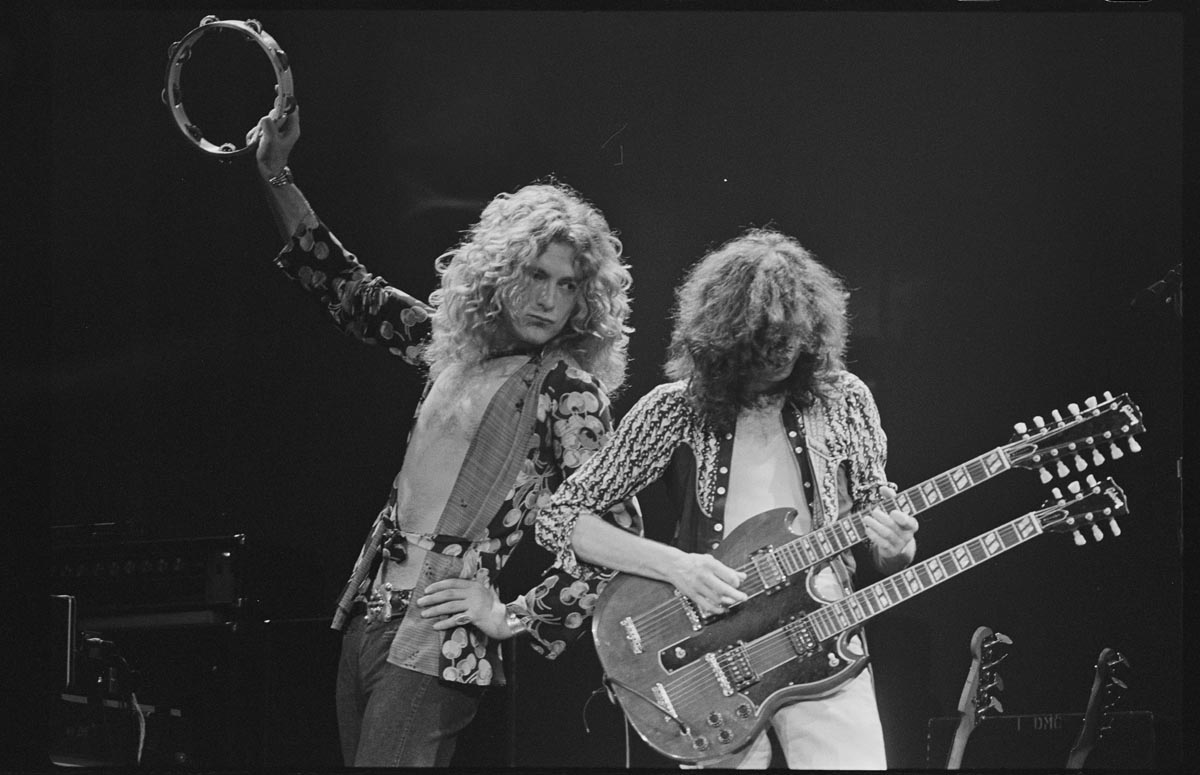

And when it came to performing the song live, you turned to the Gibson EDS-1275 doubleneck.

“Yes. I thought, what’s the guitar, how to do this on stage? And it was just obvious that the only way to do this, with the sort of fragile guitar of the opening style and the more racy sort of pickups for the solo – the doubleneck is the only way I’m going to do it.

“When I recorded the song I wasn’t thinking about how I was going to do it live. So in actual fact, the song demanded the guitar. There was no other way to do it. When you think about it, it was the only way to actually replicate that song, apart from jumping from one guitar to another on stage!“

Was that approach repeated on later Zeppelin songs?

“Well, I certainly didn’t think how I was going to do Achilles Last Stand live [laughs]. I was just doing it – I was laying on everything that I could think of that would work within the context of whatever the composition was.“

Did you miss having the acoustic guitar when performing Stairway To Heaven?

“Yeah, sort of, but it was okay doing it with the neck pickup on the six-string neck [of the doubleneck]. That was about as good as it was going to get, really. I didn’t really miss it. I was just able to take it in another direction in a live situation.

In the live performances of that song, it’s not a different arrangement, but a different feel, a different vibe.

“Yeah. The textures are going to be different, so the attitude’s going to be different. And another thing about the doubleneck... It’s after the fourth album that that arrives, so when you get to the next album after that, Houses Of The Holy, on that there’s what was originally called the Overture, but it becomes The Song Remains The Same and then The Rain Song, and I did those because I figured I would be able to do those on the doubleneck.

“So I was actually thinking of the doubleneck and being able to have those two numbers the way they appear on the album. I was thinking about how to really be able to use it, rather than just maybe for one or two songs. So it became an active part of the overall show.“

Double-tracking was a huge part of the Zeppelin sound and very influential. When did you first start doing this?

“On the first album. Don’t hold me to it, but I think you’ll find on Good Times Bad Times there’s double-tracking on the riff. I’d done double-tracking before as a studio musician, but it was difficult to do it so much with The Yardbirds because Mickie Most was the producer and we were under his umbrella, really.“

The first Zeppelin album feels less produced, more in the room, so the double-tracking is less obvious. But by the time you get to 1971 and Zeppelin IV, the production is massive. What do you feel was different then in the sound?

“I was acquainted with John Paul Jones’ playing as a session player, but John Bonham, with his approach to the drums and the dazzling technique that he had, the overall sound of his drums was unlike anybody that I’d heard before.

“It was so musical, because he knew how to tune his drums. So I knew instinctively what I wanted to do with Led Zeppelin that was unlike anybody else. I wanted to have the full stereo picture, the placing of the instruments.“

The second album was clearly going to be all about the Les Paul

And guitar-wise?

“The first album was totally based around the Telecaster. And that’s what it was – just a Supro [Coronado 1690T] amp, [a Sola Sound Tone Bender] overdrive, an Echoplex [EP-3 tape delay] and a Vox wah-wah. So it’s really very minimal and it’s not going through different amps, just this one amplifier. So it really goes to show with all the tones just how much there was that you could get out of one guitar.

“And that’s basically what it was that I had. I wasn’t using the Black Beauty or anything like that. And as it went on, the second album was clearly going to be all about the Les Paul guitar. But again, it’s a large stereo picture of everything that’s going on, whether it’s panning of things or positioning or whatever, or where things come in or go out, what’s tracked and what isn’t tracked.“

People were saying, ‘Oh, Led Zeppelin’s gone acoustic’. Well, what happened to your ears on the first album and the second album?

Things were moving very fast for you and the band at that time.

“The first album was done in a very short time. The second album was done while we were on the road in America, although we were coming backwards and forwards to England, so it’s got all the energy of touring.“

That energy was evident in the big rock numbers such as Whole Lotta Love and Heartbreaker, but the second album also had subtler songs such as Thank You and Ramble On…

“The first two songs that I had for Led Zeppelin II were Whole Lotta Love and What Is And What Should Never Be... II is almost like turning a coin, isn’t it? One side to the other as far as textures and moods...“

And then with Led Zeppelin III – released 50 years ago this month – you had Immigrant Song, a powerful statement of intent, and Since I’ve Been Loving You, this huge blues ballad, but also acoustic tracks such as That’s The Way and Tangerine...“

“People were saying, ‘Oh, Led Zeppelin’s gone acoustic.’ Well, what happened to your ears on the first album and the second album? Haha. It’s just variations on a theme, really.

“There were so many ideas put into the first album, but they were able to grow and be developed. With the third album, we had a break from touring and it gave us a chance to work on more of the acoustic stuff.“

What are your memories of making that album?

“Right at the early stages of rehearsing, when I think it was just John Bonham and myself, I had Immigrant Song, Out On The Tiles, and also Friends. If you say straight away you’ve got Friends and Immigrant Song, already it’s got the yin and yang. And there’s all this other stuff that’s going to go in.

“We’d already played Since I’ve Been Loving You before, that was written just before the third album. So we knew we had that as well. There were all these textures coming up, and I was keen to do Gallows Pole because I thought it was quite curious the way that song had started off in England and gone all the way around the States and come back, so then we were going to do it and send it back to the States again as a folk song.“

There was a clear progression with each successive album.

“Certainly within the written context of what was being presented to people to hear, everything was going to be moving forward. So when it went to the point of the more acoustic style of the third album, you can imagine our record company getting that in and going, ‘Where’s the Whole Lotta Love?’

When it went to the point of the more acoustic style of the third album, you can imagine our record company getting that in and going, ‘Where’s the Whole Lotta Love?‘

“If anyone had said that to me I’d have said, ‘Oh that, that’s on the second album – this is the third album.’ You know how it is with A&R men going, ‘Oh, you’ve got to have a single.’ We had singles in America and other places, but I wanted to stay clear of that market and keep it as an albums thing.

“Right in the early stages I demanded – after having done all the Mickie Most stuff – that we didn’t want to be a band that was known for singles. It was albums that we were going to be known for. And clearly I wanted to make each album different from the one before. “

By focusing purely on albums, you were going against the grain, against conventional wisdom in the music business. Was that difficult for you?

“No, it was not, because when the first deal was done it was established right there and then. It was good thing. That way we didn’t have people who didn’t know what we were doing in the first place – it was probably going above their heads or whatever – trying to get something for the radio.

“‘Oh, can you record something for the radio?’ All bands have heard that sort of nonsense, but fortunately we circumnavigated it by just sticking to what we knew was going to be the right way to do it, to make the music develop properly.“

It’s evident that you had a clear vision for Led Zeppelin right from the start.

“Yes, I did. I really knew what it was that I wanted to do. If you think about it, on the third album there’s Tangerine, but I wrote Tangerine back in The Yardbirds. So I’d waited an amount of time. I didn’t stick it on the first album or the second. I waited until it would fit in with the right texture of everything else. It fits great in the third album. So, yeah, I had a bit of a plan [laughs]. And not just for that one number, of course!“

Dazed And Confused was basically a vehicle for improvisation... From Robert, as well

If you were back at the time of the third album, how would you describe it?

“I didn’t really do interviews in those days, to be honest with you, but I would have just explained what it was in the context of the second album having the energy of touring, and this being the other side. Things like That’s The Way are bloody brilliant, you know?

“There’s just so much good stuff on it, and every number that we recorded was always different, it always had its own character. If anything started to sound like something else that we’d done before, we’d just stop doing it.

“We wouldn’t be doing recordings that sounded like we’d recorded it before, like a secondary version of something else, like Whole Lotta Love MKII. We didn’t do that. So yeah, I would have brought people’s attention to Since I’ve Been Loving You, no doubt about it, because nobody had actually approached blues up to that point like that. Everybody was playing blues but nobody had gone that sort of extra mile.“

There was a heavy influence of blues on the first album – in You Shook Me and of course Dazed And Confused, which turned into an epic piece in live performance...

“Well, Dazed And Confused was basically a vehicle for improvisation. There are various versions of Dazed And Confused out there, but what can be told right across the board wherever you hear it, there’s a couple of verses and then there’s improvisation – from Robert, as well.“

So you played it just going wherever the mood took you?

“Yes, there are whole areas of things that just come out on the night and then they don’t get repeated again. It’s quite extraordinary, and it keeps getting longer and longer and longer. But there’s a hell of a lot to say in that, because it wasn’t just jamming on one chord, it was going through all manner of movements like a classical piece.“

How did you set up improvisational moments?

“You go into it then you take off and try to come up with whatever you come up with along the way. But there’s a way of coming out of it, so then there would be musical signatures so that the band knew we were coming to the end of that piece and... Watch what’s coming next!

“So there were signposts, but in between you could go straight or you could go over the mountains, as far as the improvisation goes. And the improvisation was pretty fresh every night. There were character bits that stayed, for sure, but there was a lot of stuff that got played one night and never got revisited again ever.“

I knew with Whole Lotta Love that there weren’t going to be any edits. I insisted that they kept the middle section in it, which of course they didn’t like, but they had to do it

Dazed And Confused was just one of many epic tracks in the Zeppelin catalogue – alongside Stairway To Heaven, Kashmir, Achilles Last Stand...

“It was part of the overall thing from the first album. Part of it goes back to what I said about singles. With Whole Lotta Love, that was clearly going to be the track that everybody was going to go to, because that riff was so fresh and it still is. If somebody plays that riff it brings a smile to people’s faces. It’s a really positive thing.

“But I knew with Whole Lotta Love that there weren’t going to be any edits. I insisted that they kept the middle section in it, which of course they didn’t like, but they had to do it. So I thought, well, if you just keep making the numbers longer and longer... [Laughs] They’re not going to make them singles!

“I did think that in a mischievous way. But there was another reason to make them longer and longer – there was more to say in them. Then again, it could be argued the other way. Good Times Bad Times is really short, as far as minutes and seconds, but there’s just so much that goes on in that. It is what it is. Sometimes you have shorter statements. Sometimes you need longer to get across what you’re doing.“

Let’s talk about effects. The phaser sounds on Physical Graffiti, for example In My Time Of Dying and The Rover, have me thinking of Van Halen, like you influenced Van Halen. How did you dial those tones in?

“A lot of the phasing that was done in the early stages is done with tape machines. So you’ve got two tape machines running, and then with one you alter the speed so you get the phasing. Basically what it is, in those days, is an analogue effect. And then there was Eventide Clock Works, who came up with phasers, flangers and the Digital Delay Line.

“I had a really good connection with Eventide, because they were getting the stuff for me out of the factory more or less, so I got them really early on. I got the harmonizer really early as well, and I managed to use that with John Bonham. I had a Mark II Harmonizer with the keyboard, and I used that on Bonzo’s Montreux [the drummer’s showpiece track, first released after Bonham’s death on the 1982 album Coda].

I prefer to be able to fool around with things, you know? Shape the things on stage. So that’s the same with the Theremin and the Echoplex, I could just really have a real good time with those things

“It made his drums sound like steel drums, and he loved it, he thought it was great. I did have a basic unit, a foot pedal unit, and on/off one, but I still preferred all those old analogue ones as opposed to rack-mounted things.

“I had a pedalboard that grew and grew, and I was using that at the O2 for example, and that’s a Pete Cornish ’board, where he mounted all the stuff that I wanted, which is my old foot pedals into on/off stompboxes or whatever you call them, into it. I preferred to be able to do it like that, it’s something very tactile, and I preferred that to something that’s just going to come back like a metronome.

“No, I prefer to be able to fool around with things, you know? Shape the things on stage. So that’s the same with the Theremin and the Echoplex [EP-3 tape delay], I could just really have a real good time with those things.“

The Supro fits great with the Telecaster, but with the Gibson Les Paul it was a really overdriven sound, right? And when I started doing studio work, I realised that that was a bit too radical for them

Treat them as an instrument in their own right…

“Yeah, absolutely.“

If we can talk about amplification, at what point did you move on to Marshall?

“Here’s how it goes. You need to take notes or you’re going to get lost [laughs]. Basically what happens is, the amplifier on the first [Led Zeppelin] album is the Supro [Coronado 1690T] amplifier, but I got that way back, when I was art school, with Neil Christian and The Crusaders.

“That had quite a journey to it. It fits great with the Telecaster, but with the Gibson [Les Paul] it was a really overdriven sound, right? And when I started doing studio work, I realised that that was a bit too radical for them at the time. So I got what everyone else was getting, so that psychologically it looked right, which was a Burns amplifier, which I had during the studio days.

“But when Paul Samwell-Smith left the band he left his equipment behind – the [Vox] amplifier heads. I know them as Super Beatles. The way that I heard it about those amplifiers was The Beatles had them because they couldn’t hear their instruments over all the screaming, so they wanted louder amplifiers, and Vox duly obliged.“

That’s the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin I covered. What were you using during the recording sessions for Led Zeppelin II?

“I was using the Super Beatle amps with the [Rickenbacker] Transonic cabinets. So that’s exactly what’s on Whole Lotta Love. So the first album’s got the Supro; the second album, as I said, I wanted to the change the whole sound character, so that’s what I was using. I was using what was really meaty, and what I was using on stage, what I’d arrived at once I had the Les Paul Standard.

“So, by the time we get to 1969, we’ve got so much work ahead of us, and the road manager is getting really, really nervous about the amplifier going down and not getting a replacement, so they’re saying, well, everybody else has got Marshalls, so I went to Hiwatt [Custom 100s] before I went to the Marshalls.

“But then I did go to Marshall because what they’d said was absolutely true – if it broke down somewhere you’d be able to find a shop that would have one. Once I’d done the second album, yeah, the Marshall is being used by the end of those tracks [recorded] in New York. Yeah, I’ve got those during that ’69 tour.

“And I would say it has to be Marshalls by then. So maybe Heartbreaker was done on a Marshall. And that’s how it stayed, with the Marshall cabinet all the way through. Although I did take little side ventures off that, but mainly that [Marshall] was the main kit.“

I was using the Super Beatle amps with the [Rickenbacker] Transonic cabinets. So that’s exactly what’s on Whole Lotta Love

Was that also the main kit for live or just studio?

“Both. For example, Presence was done on the Marshall. I guess I had two cabinets at the top, the head and the Les Paul. So that’s it. That’s a real classic setup, really, the Marshall and the Les Paul. I was treating with that album, certainly on Achilles Last Stand, I was trying to get all the tonal aspects of the Les Paul and the Marshalls. That wasn’t everybody’s kit, to have a Supro amplifier with the Telecaster, insomuch as I knew I could get a lot out of it. I did the same with that setup on Presence.“

When did you discover the B-Bender?

“The B-Bender came as a result of listening to The Byrds, an album called Untitled, and another, Sweethearts Of The Rodeo. I really liked Roger McGuinn. His guitar parts were fantastic on those albums.

“Then I started listening to what was going on around those, I could hear this amazing lead playing that was zipping around in the background, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, how is he doing that?’ I was trying to work it out. It was really tricky to be able to do that so fluently.

“But then I met Albert Lee in Brighton one night when he was playing with Eric Clapton, and when I spoke to him about those Byrds records he said, ‘Oh, it’s a string-bender.’ Albert had one, he showed it to me, and said, ‘This is how it’s done.’

“I couldn’t see the mechanism inside it, but it worked on the straplock so that if you pushed the guitar down and you put the mechanism into play it would take the string up a tone. I thought, ‘I see! That’s how it’s done.’ So then I went about trying to get one.

“I think he may have given me the contact number for Gene Parsons. That’s how that happened, and then I started to use it for Led Zeppelin in 1977, the ’77 tour, and then it’s all over flipping In Through The Out Door [Listen to Hot Dog below for an example]. And I used it in The Firm as well, as the main sort of guitar.“

The Danelectro that you used on Kashmir has such an individual sound. When did you first start using that?

“Selmers was the big showcase shop, and I don’t know how they got away with it, but they sold every brand of guitar in there, Gibsons, Gretsches, Fenders. I don’t know how they did it, but they did.

“Suddenly the Danelectro guitar appeared in there, and [John] Entwistle had got the bass with horns on it, and this salesman was saying they had this guitar, it was only £45 or something, and all the other guitars were getting into the hundreds. I said, let’s have a go on it, and it sounded pretty great.

“Because of course it’s hollow bodied, put together with plywood. It sounded phenomenal, and I could afford it, so I thought, ‘I’ll have this as a sort of second guitar.’ I did start to use it a little bit on sessions and there’s a photograph of me in one of these big sessions with loads of guitars and I’ve taken that thing along.

“I was using it not so much on sessions, because I was using the Les Paul, but yeah, in the Yardbirds I was using it, and putting it into [altered] tunings, and it stayed with me all the way through the Yardbirds straight into Led Zeppelin.

I started to write things on the Danelectro like Kashmir because I was used to playing it in the DADGAD tuning, so Kashmir came out on that guitar, and In My Time Of Dying

“It was the backup guitar, because I was only going out there with two guitars really, in ’68, ’69 I just had just the Telecaster and the Danelectro, until I got the Gibson. So if I broke a string, I’d quickly get it into standard tuning from the DADGAD it was in and then go off.

“On the bootlegs I can’t tell the difference, I can’t tell the swap-over, which is quite interesting really. But it was there, it was a true and trusted friend, it was there all the way through.

“I started to write things on it like Kashmir because I was used to playing it in the DADGAD tuning, so Kashmir came out on that guitar, and In My Time Of Dying. They’re both on the same album [Physical Graffiti]. So clearly I was using it in [altered] tunings.“

Aside from the tunings, do you think it affected the way you played differently to the Les Paul or the Telecaster?

“Yeah, the feel of it is different. But I found it a very user-friendly guitar and I thought the Danelectros were quite consistent. We were talking about Les Pauls being very different, certainly in those ’50s ones; ’58, ’59, they really are. Of course it’s all in how they’re built, before they became more scientific about it in the approach. I found them to be relatively consistent, the Danelectros, which is always useful.“

It’s such an oddball guitar with a Masonite build…

“I know. But they’ve got those great lipstick pickups and the whole thing about it, it’s a great little guitar, and it was inexpensive, for heaven’s sake. I’ll tell you this: when I was the Yardbirds, people used to pay a lot of attention to the fact that I was playing that guitar, and definitely they were paying a lot of attention to it in Led Zeppelin, because what I didn’t know, it was in Sears & Roebuck catalogue, it was a catalogue guitar, so it was a really cheap guitar.

“How can you play that catalogue guitar, which is only tens of dollars as opposed to hundreds? How do you do that? For me it was just something I had all the time and I didn’t think of like that because I didn’t know.“

You’ve talked a lot about The Yardbirds. When you think back to when you joined that band, you were stepping into some big shoes there, following Clapton and Beck. Were you at all intimidated by their reputations?

“It wasn’t that so much. Well, yes it was. But when I joined The Yardbirds on bass – coming in for Paul Samwell-Smith – that was serious boots to fill, because I was pretty much in awe of his bass playing. I didn’t know anybody else who could play like that.

“You’d hear these really fast pulsing bass riffs and go, what the hell was that? The energy of those records with Eric, like Five Live Yardbirds, you want to check out what Paul Samwell-Smith was doing. And all of a sudden I was trying to emulate it [laughs].“

And when you switched to guitar in that band?

“Well, I didn’t actually play with Eric in The Yardbirds. The only time I did that was on the ARMS tour at the Albert Hall in the ’80s, with Jeff and Eric. But Jeff and I were playing in The Yardbirds together. When Chris Dreja was taking over the bass, Jeff and I were doing twin leads and harmonies and all of that.

“It was pretty interesting, and we had some great stuff going. Happenings Ten Years Times Ago is probably one of the best things to hear of that, or Beck’s Bolero. And when Jeff left, bit by bit I got more used to doing it all, and I knew the numbers, so I sort of just took over all of the guitar parts.“

Did your experience as a session player help you pick up songs?

“Quickly, yeah. With the Yardbirds, I thought they were the most amazing band, with the work that Eric did with them, and especially the work that Jeff did with them. I mean, he just as far as guitar playing in bands, Jeff just moved the whole thing on, as each release came out. It was just phenomenal, the guitar statements that Jeff did. I was sort of used to playing with Jeff, so I knew the parts when he wasn’t there, but then the thing to do was to come up with your own stuff altogether.“

During the ’70s, I started to get offers coming in, but whatever I had, whether it was the writing or the playing, or the production, I wanted to keep that in Led Zeppelin

Before joining The Yardbirds you worked as a producer for other artists. Did you ever consider doing so again?

“During the ’70s, I started to get offers coming in, but whatever I had, whether it was the writing or the playing, or the production, I wanted to keep that in Led Zeppelin. And that’s what it was. So the only deviation from that was my playing with Roy Harper on Stormcock (Harper’s classic 1970s album).

“He and I were playing the two acoustics, and that was really cool. I really admired Roy’s work and still do. He’s absolutely amazing. I saw him the last time he played at the Palladium in London and it was absolutely extraordinary. It was spine-chilling – the stuff he was coming up with, the new material he’d written.

“But that was the only area really where I stepped out of Led Zeppelin, because if I wasn’t on the road I was writing for the next album. I was living it and I didn’t want to not live it. I didn’t want to deviate from it or be producing someone else’s album or anything like that. No, any ideas that I had, writing or whatever it was, they would all go to Led Zeppelin.“

There is one other notable exception – the song Scarlet that you recorded with The Rolling Stones in the early ’70s, and which was finally released in 2020 on the reissue of Goats Head Soup, which was a bit of a surprise for you all. What do you remember about recording that track?

“Ronnie Wood had a house called the Wick, in Richmond. Pete Townshend lives there now. But it had a studio in the basement when Ronnie was there, a proper full studio, with a playing room and control room where you’re looking through the window into the playing area.

“I was asked over there by Ronnie, who said there was going to be a session with Keith [Richards]. So, Keith ran through this song with Rick Grech on bass and a guy called Bruce Rowland on drums, who I’d never come across before, but the bass parts and the drumming on that song are just terrific.

“Keith routined the song to me, and I just came up with a guitar part as I would if I was playing with my own band. Keith was playing the main riff and I was coming up with things to complement it. I was playing around what he was doing.

I was knocked out that the Stones put it out, because even though it was done back in the ’70s, everyone’s going full steam on it. Keith’s playing great, he always did

“So that was done in one evening, and then they were going to carry on with it the following day at Island Studio, Island number 2, and I said, ‘Well, I’ll come along and put the solos on it.’ I got there quite early on in the evening, had a couple of passes at the solo, and that was it.

“Mick [Jagger] was doing his stuff the day after that, so I left after I did my bit. It was fun, but I never thought it would come out. I was knocked out that they put it out, because even though it was done back in the ’70s, everyone’s going full steam on it.

“Keith’s playing great, he always did, and I’m happy with the guitar playing on it, I thought that was cool, so it’s nice to have that rather than a Led Zeppelin thing, you know? It’s unusual to hear me playing at full acceleration, if you like, outside of Led Zeppelin.“

Are you working on any new music at the moment?

“Well, under the circumstances of having a lockdown and isolating, I picked up the guitar and made a point of playing the guitar every day. Whereas before the lockdown, it had gotten to the point where I was always complaining that I didn’t have enough time to play the guitar because there was all this other stuff that was going on.

“It’s surprising how many things there are, even with Led Zeppelin, so I was not finding enough time to play the guitar as much as I would like. It was there, but not being played. I thought, that’s not going to be the case. I’m now going to play it. I don’t want to make it sound like I’d locked the guitars away. That wasn’t the case. But there were so many things that kept getting in the way of playing – or playing the way that you need to if you’re exploring the instrument still.“

People would love to hear more music from you, and would love to think that there’s something on the way.

“Yeah. You mean actually being seen to play?“

Yes.

“That was the idea before we locked down. But – but – there’ll be a time when we’ll be able to play, so the thing to do is to think how you’d do it of you did do it, and have some surprises up your sleeve, you know?“

I think I’m speaking for the whole guitar world in saying we’d love to hear more from you.

“I did think about it. But I thought, I better do some serious practising first [laughs], because it’s been a long time since the O2. I hope we’ll meet up one day, when I’m doing this mythical show one day!“

It would be great to see and hear you play again. But in the meantime, we have this new book of yours. For Led Zeppelin fans, and for guitar players especially, it’s a revelation.

“I’m pleased you’ve enjoyed the book, being a guitar nerd like myself. It’s a fascinating read, isn’t it? Some of those photographs I set up myself, like the doublenecks where they’re standing to attention.

“The guys I worked with on this, they’ve done a number of books for Fender, guitar books, and for one of the shots I stood the Les Paul on its side. I said, ‘Have you ever done a shot like this?’ And they said no. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding? All the guitar shots you’ve done? Well, you better fasten your seat belts, then – because you’re going to have a lot of unusual shots in this one.’“

This was clearly a labour of love for you.

“Yeah, we had a great time doing this. And you’ll know that if you’re a guitarist, you’re looking at all the details, looking down the neck and up here and down there and over the back. And I wanted to have that – what you actually see. It’s all about the guitarist’s perspective.“

- Jimmy Page: The Anthology is out now via Genesis Publications.