Burn Book is that rare thing: a book about tech that can be enjoyed by readers who are not that into tech. It is a witty and engaging account of the rise (and often fall) of internet companies and the often dysfunctional talents behind them, told by an exceptionally well-connected outsider.

Kara Swisher is somehow regarded as both Silicon Valley’s “most feared” and “well-liked” journalist. Perhaps this is best encapsulated in her rollercoaster relationship with Elon Musk, whom she knew, liked and often defended, but publicly fell out with a month after his Twitter purchase was finalised, telling him, “You may be my greatest disappointment in 25 years of covering tech.”

Swisher claims to have been born in the same year as the internet: 1962. Even as a child, “why” was her favourite word.

Her career took off at the Washington Post, where she worked from the early 1990s on internet technology. Her interest was in the Silicon Valley geeks behind it – at the time regarded as “a backwater to a backwater” – rather than politics. A much-quoted line of hers, from the early 1990s, is that “everything that can be digitised will be digitised”. This epiphany changed her career.

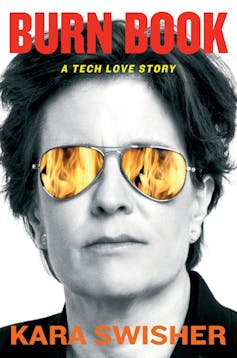

Review: Burn Book: A Tech Love Story – Kara Swisher (Piatkus)

Swisher became riveted by the succession of “total domination followed by utter collapse” of various technologies – from CD-ROMs to Myspace – and the never-were businesses that just burned through investors’ funding and crashed – including grocery delivery startup Webvan, online delivery company Kozmo and fashion e-tailer Boo.com.

‘I hope Kara never sees this’

Swisher has been described as having “a unique talent for coming off as simultaneously affable and hostile to her interview subjects”. A chief operating officer of Facebook was probably only half joking when she said Silicon Valley execs wrote on memos: “I hope Kara never sees this”.

Once when Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang was in a board meeting, another board member texted Swisher about a decision they had just made and she texted Yang to confirm the information. He texted back, asking who was leaking and she replied “it’s the whole room”.

Swisher, who later became the West Coast correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, has spent her career “being hard on powerful people”. Channelling Spider-Man co-creator Stan Lee, she believes “with great power comes great responsibility”.

Her interest in tech and being a lesbian were both unusual during her early career as an investigative journalist. She referred to herself as “Sherlock Homo”. In the United States, she is well enough known to have featured on The Simpsons, voicing herself.

Top tech entrepreneurs ‘lying to themselves’

The book is a memoir, but also a history of internet booms and busts. The title is taken from Mean Girls, a film about high-school bullies.

Swisher draws on decades of notes and articles. She kept records of her conversations from the 1990s with some of the future tech titans. She “had a sense even then that these boy men would try hard to reinvent themselves and erase their former selves”.

She observed that tech entrepreneurs often lied to her, but they were actually “lying to themselves”. She attributes this to so many of them being damaged. “I have never seen a more powerful and rich group of people who saw themselves as the victim so intensely.”

There are stories of early instances of problems that loom large today. In the early 1990s, search engine Yahoo (“yet another hierarchical officious oracle”) was facing questions about content moderation. It drew the line at bomb-making guides and child pornography, but allowed hate speech as it claimed it did not want to be a “censor”. As Swisher comments: “sound familiar?”

‘Frequently wrong, but never in doubt’

Swisher paints interesting portraits of the tech titans by someone who has talked to them many times without being beholden to them. Silicon Valley was “littered with look-at-me narcissists, who never met an idea that they did not try to take credit for”.

One common characteristic, in addition to their social awkwardness, is that many were “frequently wrong, but never in doubt”, a characteristic magnified as they became increasingly surrounded by sycophants, “most of whom are paid for their obsequiousness”.

Early on, she writes, Mark Zuckerberg almost fainted from the stress of public speaking. Privately, he dismissed his customers as “dumb” to trust him with their data. But as regulators investigated Facebook’s “sloppy and rapacious privacy practices”, he also appeared “perplexed as to why the world was being so unfair to him”. She sums him up as “one of the most carelessly dangerous men in the history of technology” and refers to Facebook as “anti-social media”.

Swisher initially regarded Musk as “one of the few tech titans who did not fall back on practised talking points, even if perhaps he was the one who most should have”. She initially excused a lot of Musk’s behaviour as “letting off steam”. But she writes, “over time, his harmless fun became less harmless and less fun”.

When he made the first moves to buy Twitter, she thought it was a good idea. “Honestly, when he started going after it, I thought this is the best person. Yeah. He could do it,” she told The Intelligencer. Swisher had hopes that Musk “could be the owner to help Twitter realize its potential”. But she now feels she was “obviously and completely wrong”.

Swisher has described Musk as “killing Twitter” but added “it’s killing Elon more than he’s killing it”. Musk reportedly called her “an asshole” and claims her supposed dislike of him as a “compliment”.

Swisher is “certain [Steve] Jobs would have despised Musk in his current incarnation” and regards Musk’s involvement with Twitter as “one of the saddest developments in my long love story with tech”.

Bill Gates had been known for his “aggressive business behaviours” but has “evolved” and Swisher has “developed a grudging respect for his forward-thinking efforts on malaria, childhood blindness, climate change and more”.

She was, at least initially, generally sympathetic to Google’s “adorkable” founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, though she still ridiculed some of their excesses.

One of the reasons for Google’s success, in addition to the brilliance of its founders and the utility of its product, was that they brought in professional management early; they had “an adult in the room”. But when the pair tried to assure her they were good people, Swisher replied she was “not worried about the good people in charge now” but “the bad people later”. She recalls “unlike the people I covered, I had studied history and I had zero doubt they would show up soon enough”.

Jeff Bezos she recalled as less awkward, but “more obviously avaricious”.

While declaring herself “not a Steve Jobs fanboy”, she thought he deserved the kudos he attracted. She admired him not just for the “meticulous design” of most Apple products but because he was one of very few tech leaders to ever admit making mistakes.

Her former boss, Rupert Murdoch, whom she calls “Uncle Satan”, was generally vexed by the internet-based challengers to traditional media, but still wanted a piece of the action. He did see Steve Jobs as a kindred spirit “whom he admired for creating wealth and power out of nothing, as he perceived he had done”.

A mirrortocracy

Many of the tech titans, she observes, worked in offices that were “an adult version of a kindergarten”.

Swisher reflects on the lack of women and people of colour in the leadership of the tech industry. While Silicon Valley liked to regard itself as a meritocracy, she calls it a “mirrortocracy, full of people who liked their own reflection so much that they only saw value in those that looked the same”. She suggests a reason the leaders so often ignore the impact on customer safety is “they had never felt unsafe a day in their lives”.

She warns the “Star Wars” version of the tech future (“which pits the forces of good against the Dark Side … [which] puts up a disturbingly good fight”) seems to be winning over the “Star Trek” version (“where a crew works together […] like an interstellar Benetton commercial promoting tolerance and convincing villains not to be villains”).

Discussing the involvement of social media in the mob attack on the Capitol, Swisher notes “in the new paradigm, engagement equals enragement”. She adds

Even if it was never the intention, tech companies became key players in killing our comity and stymieing our politics, our government, our social fabric, and most of all, our minds, by seeding isolation, outrage, and addictive behaviour.

Swisher turned down job offers from every major internet company. One reason was, she wanted to stay an independent journalist. She also realised she was “far too much of an irritant to survive until my shares vested”. As she puts it, “instead of having piles of money to jump in, I get to say: f*** your metaverse, Mark”.

By 2020, she described herself as a “cranky Cassandra” and became more interested in the regulation (or lack thereof) of the tech industry. A move to Washington DC to be closer to her older children helped forge relations with government officials. These days, she is perhaps best known as host of the New York Magazine podcast, On with Kara Swisher.

But while not shying away from the problems that have arisen, Swisher remains a tech optimist at heart. In her own words, she is “an optimistic pessimist” who expects the worst but still hopes for the best. More often than not, she writes, she is “happily surprised” by people’s better natures – “leaving Musk out of this as he screws up the chart badly”.

Turning to the more recent tech manifestations, Swisher is fairly unimpressed by Zuckerberg’s metaverse. But she sees great potential for good in generative artificial intelligence, which could “discover new drugs that that will solve cancer […] turbocharge education across the globe […] come up with new ways to solve the climate crisis”.

But she also sees great potential for harm. It could also “become self-aware and kill all of humanity”. It depends who controls it. She is “fearful of bad people who will use AI better than good people” and believes this is why “it is ever more urgent that we take back control”.

One annoying omission is an index. As Swisher writes, “you have to read the whole book all the way through to see if you’re in it”. But Burn Book has some great lines. This review would be far too long if I were to include even just my favourites, but one of them – and an appropriate note to end on – is:

I leave you to your own devices […] I mean that: your phone is the best relationship you all have now, the first thing you pick up in the morning and the last thing you touch at night.

John Hawkins does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.