It’s worth remembering that not all musicians had influence during their lifetimes. For example, Robert Johnson, as iconic as he is now, died in obscurity with his incredible music only making an impact decades after his death when his recordings were rediscovered as the ‘blues revival’ gained traction in Europe.

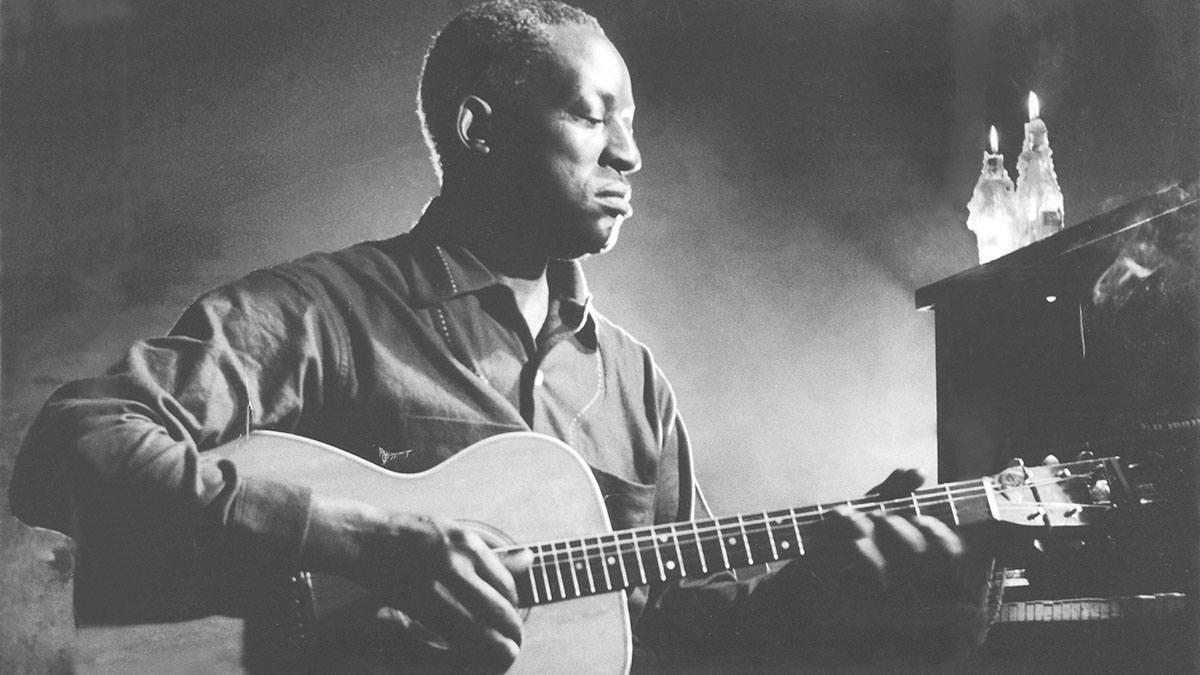

Of those who did have an influence at the time, William ‘Big Bill’ Broonzy stands tall. Even now, 65 years after his passing, Broonzy continues to influence blues musicians as much as he does folk, country and jazz artists – just as he did way back in the 1920s when his powerful voice and guitar was first unleashed on the record-buying world.

Separating fact from fiction in the story of Broonzy’s life is complicated. Like many early blues artists that found second careers in their later years, he was prone to contradiction when it came to his own life events and his place in the lives of other artists. Was he born, as he claimed, in 1893? Later research suggests maybe 1898 or 1903. Was he born in Mississippi or Arkansas?

What is known is that he was one of 17 children. Not all survived. He was one of twins, the other being a sister. His father, Frank Broonzy, also went by the name Bradley. His mother was Mittie Belcher. The musician claimed his father also had six children by another woman. Broonzy states: “My mother only found out about that after he died. If she’d known before, he might have died sooner!”

Big Bill Blues, Broonzy’s autobiography, was published in 1955. Despite accusations of untruths and inaccuracies in the narrative, it’s still an important document, one of the few we have from the ‘horse’s mouth’ and worth reading in context.

Origin story

Broonzy grew up near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and became involved in music at a very young age, playing spirituals and folk songs on a homemade violin. Along with his friend Louis Carter, who played a homemade guitar, they played at social events and church functions.

Back in those days, blues formed only a part of the average gig and was a predominantly female-led musical form. Musicians were expected to provide everything from waltzes and polkas, to folk songs and Tin Pan Alley numbers; blues was generally used for end-of-evening slow dances and would never be performed at a church event.

Around 1915, Broonzy was married and working as a sharecropper. He later claimed he joined the army in 1917 and was sent to Europe, although the draft records show no evidence of this.

What is true is that he moved to Chicago around 1920 and, shortly after, switched from violin to guitar. He took lessons from Papa Charlie Jackson whose most enduring recording is his 1924 version of Salty Dog Blues. Honing his skills at rent parties and social events, Broonzy also worked as a porter, a cook and at a foundry.

Through his connection with Charlie Jackson, an audition at Paramount Records resulted in Broonzy’s first recordings. Alongside vocalist John Thomas, a string of poorly received records were released in 1927. They were, however, enough for Paramount to retain Broonzy’s services until 1932 when he went to New York and signed with the American Record Corporation, a company that controlled several small labels releasing ‘race records’.

In 1934, he switched to Bluebird Records. By now, the Broonzy that was to become such an influence was starting to emerge. His voice was assured and his guitar playing had acquired that drive and purpose that eventually led to the emergence of R&B and, later, rock ’n’ roll.

As his stature grew throughout the 1930s, a big break came his way when he was asked by producer John Hammond to appear at the legendary From Spirituals To Swing concerts that took place at Carnegie Hall in New York City in 1938 and 1939. Ironically, Broonzy was the replacement for the recently deceased Robert Johnson, an artist that Hammond was interested in promoting.

Had Johnson survived, this would have been his own break into the mainstream. Broonzy then landed a role on Broadway in the show Swingin’ The Dream, a Black adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, starring Louis Armstrong.

Broonzy always described his music as ‘country blues’. Unlike the slide-dominated Delta style, his approach to guitar was a curious hybrid for the time. Elements of vaudeville, ragtime, jazz and country informed the musician’s playing as much as the blues did. In a way, this indicates Broonzy’s versatility as an artist. A versatility that, perhaps, was stifled by his record label’s insistence that he commit only the blues to shellac.

Broonzy – like many other early bluesmen – is almost impossible to copy. There is so much rhythmic and dynamic subtlety going on. The notes may sound easy, but the delivery is complex

Broonzy himself had said, in the early days, Black musicians were well-versed in country music as much as white musicians were in the blues. In the words of another legend, Lonnie Johnson, they were “musicianers” capable of straddling genres and constantly mixing with each other and learning from each other.

It was really a marketing decision to pigeonhole country as ‘white’ and blues as ‘Black’. Record companies held sway over what artists were asked to record and it’s been that way, for the most part, ever since.

With his right thumb providing a relentless bassline, while he picked out melodic figures with his first and second fingers, Broonzy had a rhythmic drive that often makes one forget there’s only a guitar providing the accompaniment. As simple as it may sound, Broonzy – like many other early bluesmen – is almost impossible to copy. There is so much rhythmic and dynamic subtlety going on. The notes may sound easy, but the delivery is complex.

Early recordings such as Long Tall Mama epitomise this. How he sings so freely over his syncopated guitar at the same time is staggering; he makes it flow with such ease. The influence of Broonzy’s early training as a fiddle player comes across in the solo licks he drops in with what seems like no effort at all. Saturday Night Rub rocks along with its walking bassline and melodic figures acting like a call-and-response. It’s a piece that still baffles fingerpickers to this day.

Broonzy’s sense of rhythm truly is second to none. How You Want It Done is another guitar tour de force. The focus is on the bassline here, a line that can only be described as proto-rock ’n’ roll. Interspersed with biting chord stabs, and Broonzy’s lazy vocal floating over the top of his relentless guitar playing, it’s a truly phenomenal performance.

Throughout the 1930s, Broonzy’s popularity and reputation grew. Stylistically, he stuck to his guns as the music world changed around him and he really came into his own as a performer and songwriter during this period. Into the ’40s, he expanded somewhat, somehow managing to retain his country roots but adding a more urban element to his music.

He was afforded more leeway in the recording studio to demonstrate his mastery of blues, ragtime, country, jazz and spirituals – contrasting styles that he managed to mix together so perfectly that one could forget that he was blending so many musical approaches all at once. They all came out sounding as one, something that takes a huge personality such as Big Bill Broonzy’s to pull off.

Towards the end of the 1940s a new generation started to take an academic look at America’s early music and its musicians. This happened with blues, country and jazz. Something of a ‘revival’ scene started to grow and Broonzy was perfectly placed for a career shift that kept him busy for the rest of his life.

The road to Europe

1949’s I Come For To Sing was one of the first of these revival touring troupes and Broonzy was a centrepiece of the show. By 1951, Europe beckoned and he embarked on the first of several tours there.

At first, his recent sophisticated, urban approach was greeted with suspicion, with many concert attendees mistakenly believing that blues was played by poor people in dungarees and straw hats.

Noting this, Broonzy made a full return back to his country roots and, from then on, never wavered saying, “I don’t want the old blues to die because if they do, I’ll be dead, too!”

As the first of the original blues masters to tour Europe, Broonzy was in a great position to take advantage of the interest these new audiences had in the music of his time.

And he soon became a huge influence on the young rock ’n’ rollers that would go on to be household names in the ’60s. Broonzy performed to packed houses and standing ovations, night after night.

Just him, on stage alone, his voice and guitar coming across like it was from another world. And, literally, it was! Recordings from his European sojourns reveal an absolute master of delivery, timing and pace. The concerts flowed so effortlessly and were so intimate that packed theatres transformed into small bars.

Broonzy’s trips to the UK during this time would go on to change the future of pop and rock music. British audiences, hungry for blues, received their schooling from Big Bill Broonzy.

Later on, Muddy Waters, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee followed in his footsteps as a new ‘blues boom’ began to take hold. Bert Jansch, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Steve Howe, Rory Gallagher, Eric Clapton and Ronnie Wood are just some of the musicians born out of the blues boom that have cited Broonzy as their inspiration.

Lennon, Paul McCartney, Steve Howe, Rory Gallagher, Eric Clapton and Ronnie Wood are just some of the musicians born out of the blues boom that have cited Broonzy as their inspiration

Now into the mid-’50s, 1956 saw yet more touring in Europe for Broonzy, but the performances were now also taken to Africa and South America. Finally, he could make a good living from his music. Up until this point he had always needed to supplement his income with the ‘day job’.

Broonzy had always wanted to go to college. Despite his fame and mastery of the blues and spirituals, it always remained a dream for him. In his autobiography he wryly thanks two people, Dr Shelleter and Mr Pemburg, for “making my dream come true… they got me a job as a janitor at Iowa State College…”

Rise and fall

Broonzy’s lifestyle began to catch up with him in the mid-’50s. Along with the issues that come with a lifetime of smoking, drinking, constant touring and working a series of menial jobs, he was diagnosed with cancer in July 1957. Despite this, his big masterpiece was just around the corner.

Between 12 and 14 July 1957, Broonzy waxed one of the most incredible documents in music history. Known today as the Last Sessions, it comprises nearly 10 hours of Broonzy playing, singing and talking. The first evening saw Chicago suffer one of the worst storms it had seen. Cool as ever, Broonzy made it to the studio posing the question: “It’s a helluva night, is there gonna be any whisky?”

Nobody, except perhaps the man himself, knew that these would be his final recordings and they now serve as his musical ‘last will and testament’. Broonzy had his first operation for his cancer the next day.

A subsequent surgery in September severed his vocal cords and he would never sing again. As 1958 progressed, so did the cancer, spreading from his lungs to his throat. A benefit concert was arranged, which Broonzy was just about able to attend. The concert raised $2,000 to cover his medical expenses, the equivalent of over $21,000 today.

On 15 (or 14, sources vary) August 1958, Big Bill Broonzy died in an ambulance on his way to hospital for more treatment. His funeral was attended by the likes of Tampa Red and Muddy Waters, and Mahalia Jackson sang at the service.

Despite a brief flirtation with electric blues in the ’40s, Broonzy stayed loyal to the acoustic country blues. But it was more than it seemed on the surface. His unique blend of blues, ragtime, work songs, country, hokum and spirituals allowed his influence to spread far and wide. His songwriting covered a multitude of subjects from love, hardship and folk tales, to discrimination, bad luck and travel.

All underpinned by guitar playing that is as joyful as it is, at times, heartbreaking; as melodic as it is relentlessly driving, all laced with a subtlety and romance that make Big Bill Broonzy one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.