Why do authors pen memoirs? What impact can memoirs have? Patti Miller, an expert on writing “true life”, says authors should ask why their memoir should be written.

Miller believes there are good reasons to write a memoir – maybe the author has a particular wisdom to impart or wants to assert a sense of identity. The memoir might be a healing document, or it could be filling a gap in social and cultural history. It might be even be written as revenge (although Miller cautions against this). But ultimately, the memoir holds the possibility of enlightening the reader.

Review: Between Me and Myself: A Memoir of Murder, Desire and the Struggle to be Free by Sandra Willson, edited by Rebecca Jennings (Text Publishing)

All of Miller’s categories for memoir/autobiography come into play in Sandra Willson’s Between Me and Myself. After killing taxi driver Rodney Woodgate in 1959, in an act she says was revenge against a society that forbade her relationship with a woman, Sandra became New South Wales’s longest-serving woman prisoner. She was detained for 18 years in psychiatric hospitals and prisons before her release in 1977.

Read more: Women in prison: histories of trauma and abuse highlight the need for specialised care

A searing indictment

This book offers heartbreaking detail of trauma, abuse and neglect, and a searing indictment of Australian society and its institutions.

Willson’s story highlights a period in Australian history – the 1930s to 1990s – from the perspective of someone who was marginalised and discriminated against. She shows how gender identity and sexuality can be suppressed and then embraced.

Willson demonstrates that healing is possible, but also offers cautionary words about reliving trauma. There is an element of revenge too, but this is kept to a minimum.

Her story is painful and difficult, and tells us much about gender, sexuality and class in Australia (particularly in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s). It’s a story that almost didn’t make it to print, with an almost-forgotten manuscript that ended up with a historian, Rebecca Jennings.

Willson died in 1999, and Jennings came across her story while researching a history of lesbians in Sydney. She ended up taking on the manuscript (with the permission of Willson’s family) and editing it down for publication.

She also wrote an introduction and afterword for the book, which provides the reader with context and a coda. Jennings describes the book as “a powerful account of a life lived on the social margins of postwar Australia”, and I would have to agree.

Much of Willson’s memoir was written while she was incarcerated. She writes that she spent periods of her youth in a “girl’s shelter” after being arrested for living with another young woman – an event that triggered “awful consuming anger due to injustice”.

After setting up a home with her, Willson and her partner were subjected to a police raid. Pulled from their home, they were sent to a girls’ “shelter”. Willson describes the moment she was separated from her love:

I kissed Barbara for the last time. The policewoman did not seem to approve of this, but said nothing. I knew that if I did not kiss her now, I would never be able to consciously remember which kiss had been our last. Then the cops were back inside, forbidding us to take any of our property with us …

Life in the girls’ shelter was harsh and included the humiliation of a doctor’s examination, “a fearfully intrusive and painful experience”, and no comforts. Willson was unable to find any reprieve from the judgements of the staff:

frantically, I ran from spot to spot in the yard, vainly trying to find a place where I could be sheltered from all eyes […] there was no such place. The yard had been constructed to give no shelter, no hiding place to its inmates.

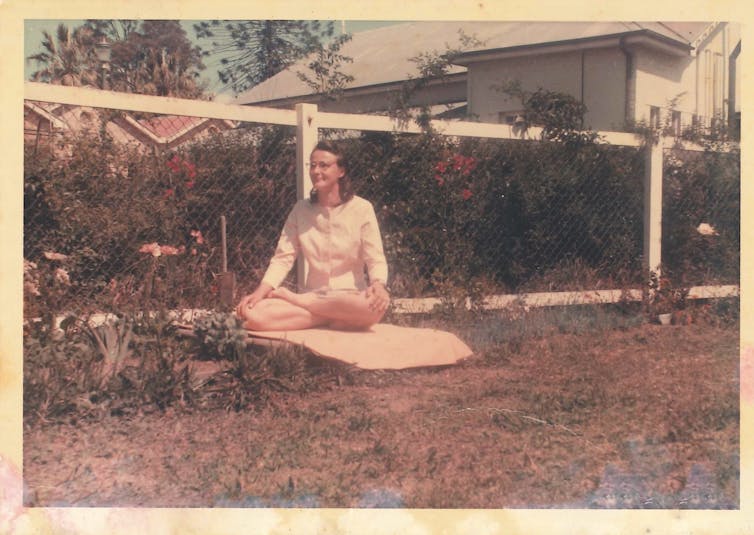

In October 1958, after being released from the shelter, and a stint working as a housemaid at the Kings Cross Hotel where her mother was head housekeeper, Willson became a trainee psychiatric nurse. Arrested for murder in 1959 as a 20-year-old, she was sent to a secure psychiatric hospital after being found not guilty due to insanity. She spent 11 years as a psychiatric patient, and a further seven years in prison.

This information is on the record and not too hard to find (stories of Willson have been aired previously in different forms), but Willson’s memoir brings this period to life and includes great detail of the day-to-day experiences in the hospital and prison, as well as a deep insight into Willson’s emotional, psychological and physical state during this time. It reveals how Willson was discriminated against due to her sexuality, and vividly illustrates the brutalities of incarceration.

Working-class survival skills

This is a conventional memoir in terms of form – Willson had been a committed diary/journal writer and she used these entries to construct the memoir, which is structured chronologically and begins with her birth.

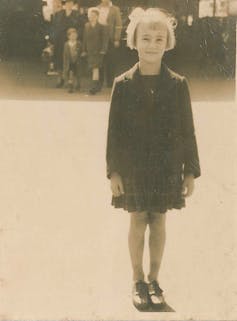

The scene is briefly set in the first two pages (she was born during World War II, was briefly fostered when her parents signed up for war duties, and then lived with her grandparents until the end of the war).

But on the third page she describes, in a detached and matter-of-fact manner, being molested by a man at her cousin’s house, ending the section with “so I walked out, feeling angry and worried, and hoped he wouldn’t offer me any more biscuits”. This sets the tone for the rest of the memoir.

The scene is horrifying, but more so because of the tone – it is clear that as a child, Willson had no one to turn to and had to deal with this abuse (and more that followed) by herself. A sense of hardness and detachment comes through the writing.

Despite the extreme emotions Willson experienced (and displayed later as an adult), this detachment is how she managed to survive. As Willson reflects, “I did not dare allow myself to be vulnerable because I feared the damage staff could do if I dropped my protective front”.

In Willson’s working-class environment, an ability to “get on with it” was often necessary. For young working-class people like her in the 1950s, there was no access to sympathetic adults or counsellors to help her process her trauma, understand her identity and navigate a hostile society.

She was left on her own to try to figure out her gender identity and sexuality – and the lack of role models or guidance led to many uncomfortable and dangerous situations, such as developing obsessive feelings for unavailable women and being taken advantage of by men.

Her class background also meant that while Willson had shown ability in academic learning, she was unable to pursue her education and worked in various working-class jobs until ending up incarcerated. (She did train and work as a psychiatric nurse, but this was not considered a professional occupation at the time.)

Through Willson’s own words, we see the daily discrimination she faced as a young queer person, and witness the pain of her attempts to find love.

The pain she experiences after losing another chance at love is, she says, what led to her shoot Woodgate. Willson was overwhelmed with hatred and decided to “fight back”, choosing a taxi driver because she had been sexually harassed in the past by male drivers.

Not that she suggests this is an excuse for what she did – and she takes responsibility for the killing – but through her words, we can understand why she did something so terrible.

Read more: As Wentworth slips quietly onto the ABC, the series still asks tough questions about gender politics

Same-sex love punished

In her introduction, Jennings explains that Willson was acutely aware of the ethical implications of publishing her memoir, not just in terms of the impact it might have on the family of the man whose life she took, but also on the women with whom she had relationships (both romantic and platonic).

Willson understood that the women she loved had to hide their sexualities. And while she was often angry when heartbroken, she did not blame the women for denying their relationships with her. She knew that society’s attitudes towards homosexuality were to blame.

This runs through the whole memoir. Willson is angry at society for denying her the chance to be herself and to live her life as she wished. She is angry with society for demonising, pathologising and criminalising her sexuality.

Her anger is also directed at the people who tried to control every aspect of her behaviour, from her clothing choices to the way she spoke (while incarcerated, she was often punished for swearing and using coarse language).

She is angry at the brutal treatment of psychiatric patients who are physically and chemically restrained, placed in solitary confinement, not given access to proper psychiatric treatment, and locked up unjustly for a variety of “deviant” behaviours (such as being a lesbian or being a teenage parent).

These experiences mean her emotional development and self-esteem are “virtually non-existent” and on many occasions, she attempts self-harm.

So what does the reader learn from Willson’s memoir? We learn that society was homophobic and that same-sex love was criminalised and punished. We learn that the criminal justice system and its institutions have been brutal and caused much damage.

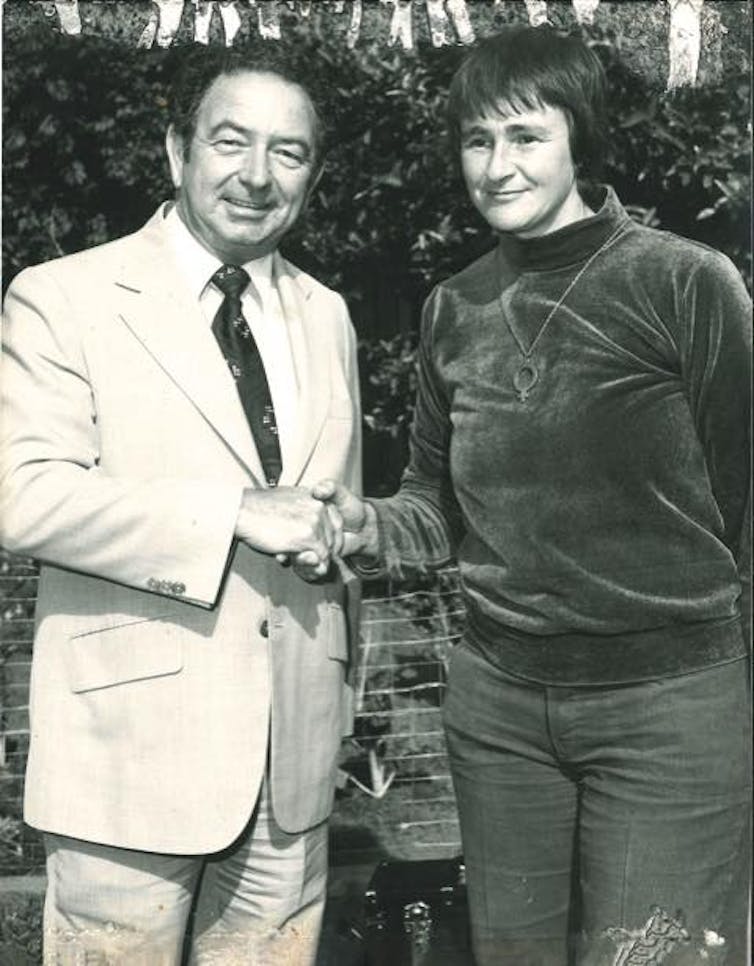

But we also learn about resilience. Not the neoliberal type of resilience spouted by well-being champions in corporate contexts. Willson’s memoir demonstrates working-class resilience. She survives being incarcerated – and once released, she devotes herself to helping women in similar circumstances. She opened and ran Guthrie House, a hostel for recently released women prisoners. Willson also worked with the producers of the TV show Prisoner - advising them on the reality of life inside.

It also shows the importance of middle-class activists working alongside working-class people to push for change that positively impacts working-class life (such as the members of advocacy group Women Behind Bars, who started a campaign for Willson’s release). Importantly, Willson’s experiences also point to the need for rehabilitation, rather than brutalising punishment. As she states towards the end of the memoir:

There are better ways of responding to acts which are deemed to be criminal and unlawful. Especially if the response is tailored to the individual and not the individual bashed into the framework of the response. The ultimate aim should be […]real meaningful rehabilitation.

Between Me and Myself is not an easy read, but it is a necessary one.

Sarah Attfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.