In 2020, the year Vincent Namatjira was awarded the Archibald for his double portrait with Adam Goodes, I was also impressed by the painting hanging next to it, Blak Douglas’ (aka Adam Hill) Writing in the Sand. It was both passionately political and visually very clever, incorporating the speech that the 12-year-old Dujuan Hoosan gave to the United Nations.

One of the many unwritten rules of the Archibald is that the winner is often an artist who has exhibited an outstanding (non-winning) work in previous years.

But this year, Blak Douglas’s winning portrait is the standout entry, head and shoulders above the rest.

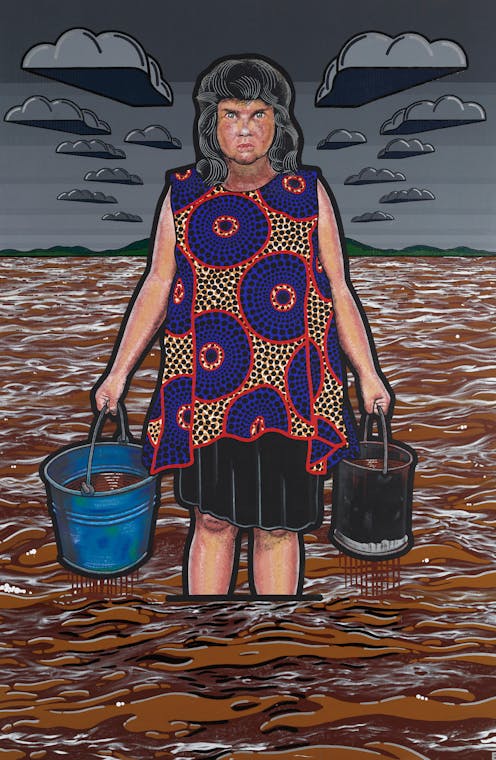

It is not just the subject that makes it significant and topical, although that helps. Karla Dickens, a Wiradjuri woman, lives in Bundjalung Country in northern New South Wales.

When the prize was announced, Dickens described herself as “a grumpy white sperm whale in muddy water ready to rip the leg off any fool with a harpoon who comes too close”.

The people of Lismore and surrounding districts have every reason to be enraged at the politicians who come with platitudes instead of help. The people are left to wade through muddy waters with leaky buckets. Dickens herself harboured three homeless families in the immediate aftermath of the floods.

Douglas has painted Dickens standing under a dark grey sky patterned with 14 stylised clouds, symbolising the 14 days of continuous rain that brought the floods.

Douglas’s style owes a great deal to commercial art. The subject is outlined in black for emphasis, even the mud forms a pattern. Dickens stands full frontal, scowling at the viewer, uncompromising in her anger at the folly that has led to this mass destruction. Her feet are concealed by mud, the kind of sludge that still fills and stinks the houses as people try to survive.

I can’t think of a more timely painting, as it so effectively encapsulates the current mood of the country.

In his acceptance speech, Blak Douglas noted he has spent “20 years of taking a risk” before he stood on the winners podium with a prize of $100,000. He reminded the gathering of media and patrons that, especially in recent years, the lives of artists are both hard and uncertain. Not all are winners.

Read more: The Archibald 2022 finalists: sitters speaking up to power; artists speaking back to the canon

The Wynne Prize

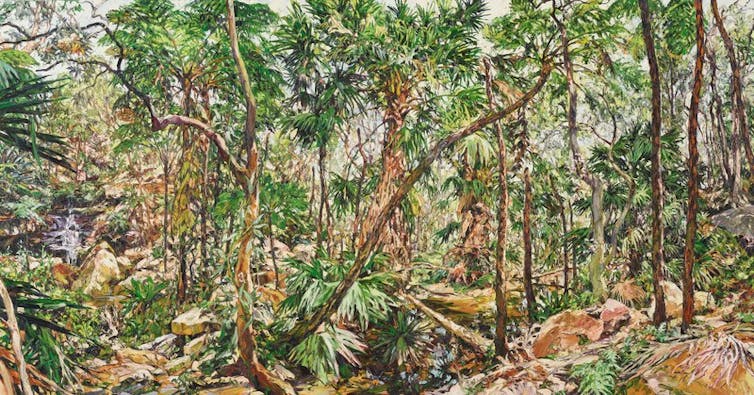

Nicholas Harding, who has been awarded the Wynne Prize is not an Indigenous artist, but his painting, Eora, also references Australia’s Aboriginal heritage.

The subject is based on the Narrabeen Lakes walk, north of Sydney. It is one of the largest works exhibited. Harding’s characteristic impastoed surface evokes the lush vegetation of the land before the colonists came to fell the trees and kill the ferns.

Interestingly the painting was not painted for the prize but as a commission for two private collectors who are long-term admirers. Harding is a nine time finalist in the Wynne, and says the decision to enter was “a last minute thing”.

His hesitation is understandable as every year, even being hung can be a bit of a lottery.

The Sulman Prize

The Archibald and the Wynne are judged by the Trustees of the Art Gallery of NSW. Not so the Sulman Prize, which was established as a bequest of Sir John Sulman – one of the Gallery’s most conservative trustees. The brief is for a “subject or genre painting”, but over the years that distinction has become meaningless.

Because it is judged by a different person every year, its outcome is less predictable.

It is worth noting that this year, 69% of the Sulman entries were by artists who had never before been hung. This is in marked contrast to the Archibald (27%) and Wynne (50%) finalists.

As is common practice this year’s judge, Joan Ross, was a previous winner and is also an Archibald finalist.

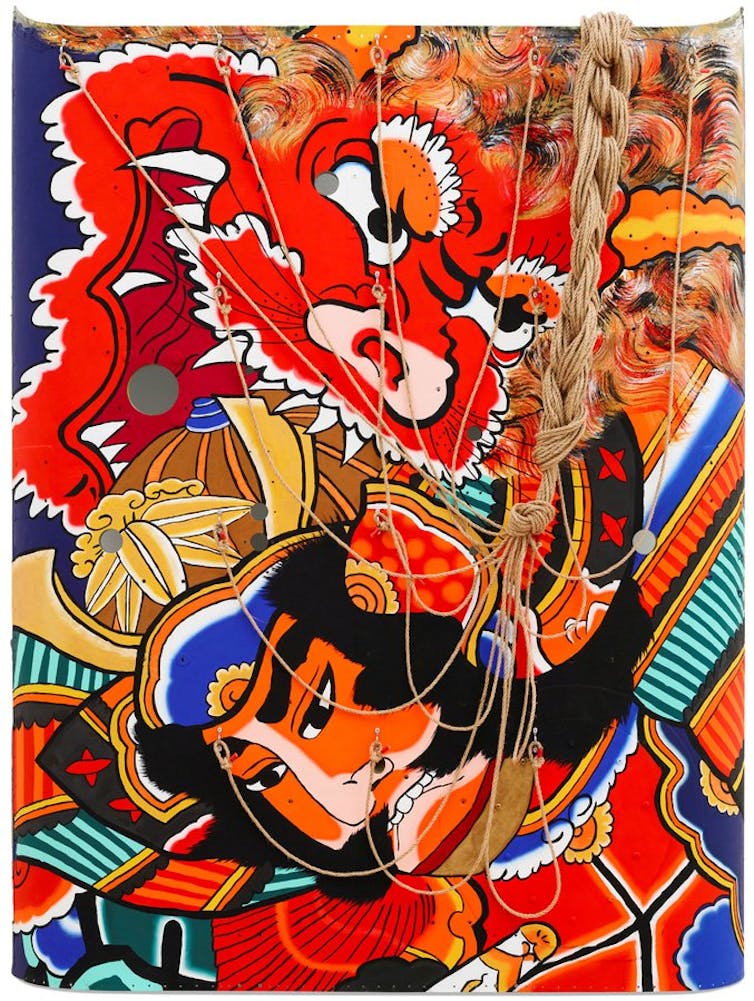

The winner is unusually a duo – Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro – who formed their artistic collaboration when they were undergraduate students. Over the last 20 years they have created installations both large and small, including at the Venice Biennale.

Raiko and Shuten-doji is painted on a piece of an army surplus helicopter, so that the Japanese legend of the warrior Raiko and the demon Shute-doji can be viewed through the lens of military conflict. But then they turn it back into a kite: a playful thing.

Joanna Mendelssohn has received funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.