“What you mean laundry shared?” 27-year-old Dima asked me in his clipped Slavic accent over Zoom.

“Washing machines in apartments are not common in New York,” I told him.

Dima scowled and muttered, “Not sanitary,” in Russian under his breath. I remembered how odd I had thought it was to have a washing machine in place of an oven in my previous apartment in Kyiv. Back then, I was an American experiencing culture shock. Now, I was preparing two refugees to do it all the other way round.

“Any other questions?” I asked. It felt like the millionth Zoom conversation I’d had with Dima and his mother, Katya, over the past seven months. Ever since I’d offered to sponsor them to move to the US from war-torn Ukraine, we’d been laying the groundwork together for a successful move. We’d discussed everything from the history of Ellis Island to New York weather patterns to their choice to leave behind their two cats, Nick and Shere Khan, in Kyiv with friends. I was trying my best to get Dima and Katya ready for life in the US, but I knew nothing could fully convey how different things would be once they arrived.

“No. Thank you, Clare,” Dima said, in answer to today’s question. “See you soon.” Then he logged off for the final time.

From 2014 to 2019, I worked as a preschool teacher at an international school in Kyiv, and made the former Soviet republic my home. I’d always wanted to live abroad and so, when the opportunity came up when I was 27 years old, I jumped at the chance to live in Ukraine.

After I repatriated back to New York in 2019 to attend graduate school, I missed going to cafes with my friends, swimming at the Olympic-sized pool called Yunist in the city center, and walking around the elegant capital full of outdoor markets, gold-domed churches, and vibrant murals. I missed speaking Russian with my Ukrainian colleagues and students, attending Russian classes after school for ex-pat teachers, and meeting with my language exchange partner at Pazuta Hata for tea and napoleons. Kyiv had a special place in my heart.

Shortly after Putin’s invasion began on February 24, 2022, I watched the scenes of devastation on my iPad with horror. I sent encouragement to my friends and the families of my former students in Kyiv, but it didn’t feel like enough. So, when Biden began the United for Ukraine program that allowed American citizens to sponsor Ukrainians and bring them over to the country under their guidance, I knew I wanted to get involved.

My mother hoped I’d be able to sponsor the man she wished I’d come home with instead of my cat, except he couldn’t leave the country. Another Kyiv-based friend who I approached with an offer of sponsorship didn’t want to leave her husband. A former colleague that I was almost all set up to bring over unexpectedly had a family emergency, and could no longer leave Ukraine. I moved further down my list and proposed sponsorship to my former swim coach in Kyiv, Katya, as well as her son Dima. Dima had a medical exemption from the Ukrainian army, so, unlike most men, he would be allowed to cross the border.

I met Katya in 2016 through a colleague’s recommendation, when I was desperate to work with an experienced coach who would be patient with me since I didn’t speak Russian very well at the time. During our first training lesson at Yunist, Katya placed a giant black sponge around my ankles. I immediately sank towards the bottom of the pool, and was forced to use all of my muscles to push my way back towards the surface. “To go fast, you must first go slow,” Katya told me in Russian. “Swim.”

Three years later and back in the United States, I was now 35, single, living off my savings, and looking for work following graduation. Katya had taught me so much about sport and resilience during my time in Kyiv. Now it was time to pay her back.

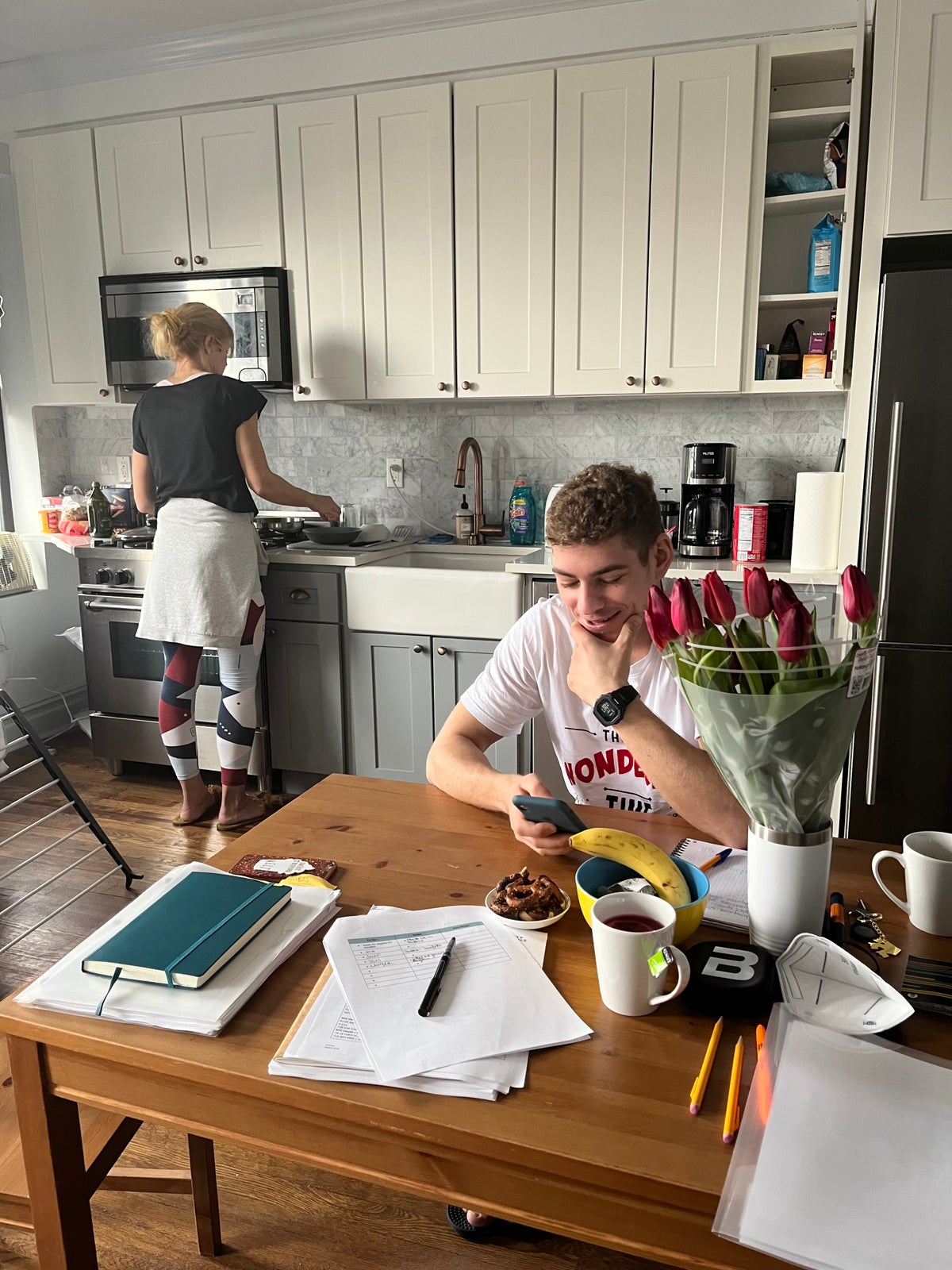

And it turned out that sponsoring a Ukrainian refugee family is complicated. Really, bureaucratically complicated. But since my schedule was flexible, I had time to navigate the complexities of filing the I-134 forms; to make calls to lawyers, bankers, Catholic charities, missionaries, and UCIS; to scan, complete, and submit the massive amount of extra paperwork needed for sponsorship; and to Zoom and WhatsApp with Katya and Dima about the everyday realities of living in America. During spare moments, I wrote cover letters and applied for jobs. Checklists, forms, and scanned photocopies of official documents overflowed from my desk.

Six months later, I whooped when I received an email notifying me of travel authorization for Katya and Dima. I quickly messaged them, sharing the good news. Then I booked their one-way flight from Poland with frequent flyer miles. They would have to make their way through Ukraine and across the Polish border to get on the plane.

A week before she traveled from Kyiv to Warsaw to make the eight-hour flight to New York, Katya asked me, in Russian, “Would you like anything from Ukraine? Salo? Vodka? Roshen?”

“No,” I said. “Just you.”

On Friday, February 11th, Katya and Dima arrived at Newark Airport. I spent the morning at the new apartment in Elmhurst, Queens that I’d arranged for them after finding people in my extended social network who could assist with housing. All through the early hours of the day, I unpacked shipping boxes from Walmart, Amazon, and Target filled with sheets, bedding, pillows, cleaning supplies, towels, dishes, and an electric kettle. Pulling off the plastic from the household goods, I washed the dishes, made the beds, and stocked the refrigerator with kiwis, salami, cheese, and sourdough bread.

Then I drove through the bridges and tunnels of New Jersey to Terminal B, arriving an hour after their LOT flight landed. I snacked on hummus, kettle chips, and Diet Coke as I anxiously checked the monitors and gazed at the steady stream of arriving passengers. Two hours later, I finally spotted Dima schlepping a duffle bag and large suitcase completely wrapped in plastic. “Dima! Katya! Over here!” I called. We opened our arms wide and embraced each other. It felt as if no time had passed. Once again, our paths had merged into a single lane.

As a classic introduction to New York life, for their first Saturday in New York, I took Katya and Dima to a diner in Elmhurst. Leafing through the laminated pages of the menu, Katya was disappointed to discover that solyanka soup — a Russian concoction dating back to the 15th century that is traditionally made with salty meats, sausages, olives, pickles, and lemon — was not listed. Her face contorted as she saw that crackers, not bread, were placed next to the turkey cream soup the waitress placed in front of her. She lifted the liquid skeptically, and hesitantly tasted the yellowish goo. Then: “Look Dimchick, look!” Katya motioned to Dima and pointed to the table across from ours, where a couple was having brunch. “American pancakes! So big!”

I paid the bill and we left the diner. Zipping up our coats, we walked back toward their apartment while I pointed out shops, the local Duane Reade, their metro station by the 7, and the corner grocery store. Katya cooed over the displays of heart-shaped balloons, red roses, glittering containers of candy, and pink-hued teddy bears.

“Clareochka, what this?” she asked me in Russian.

“It’s Valentine’s Day next week,” I explained.

“Ahhh! Love day, yes?”

“Yup,” I replied, “The 14th of February.”

The following weekend, I took Katya and Dima on a tour of the city. Dima was keen to see an Apple store in real life, so we visited the one by Grand Central Station. We stopped for coffee at Bryant Park before continuing on for 30 blocks to Central Park so he could see a squirrel.

We fed the sparrows almonds as we drank cappuccinos. I was impressed with how much Dima’s English had improved. Over coffee, he explained that while waiting for the US to provide travel authorizations, they’d traveled to Germany, hoping to find a temporary safe place to live. During that time, which ended up stretching into six months of arduous waiting, everyone had spoken English to them, and so Dima’s English communication skills had improved dramatically since we’d last spoken.

“We go see this?” Dima asked, showing me a picture of a T-rex fossil on his phone.

“Sure!” I chirped, “We can go there tomorrow.”

“I learn about in university,” Dima said. “I want go see.” I thought about the Ukrainian Natural History Museum that I took my students to on field trips while in Kyiv. Housed in an elegant blue mansion, it featured a reconstructed Paleolithic hut, a giant mammoth fossil, and displays of Crimean and Carpathian animals, penguins, pinned sea creatures, and stuffed birds. The one thing notably not present: dinosaur bones. No wonder Dima wanted to go to the one here in New York.

On Monday the 20th, we visited the American Museum of Natural History, and surveyed the taxidermized animals and fossils on display. “I can’t believe this real,” Dima exclaimed posing for a picture in front of the gigantic dinosaur, “I’d like to buy present for my friend’s children.”

We roamed through the various halls, examining ocean life, gemstones, and the hall of human origins, when Katya suddenly stopped in front of a humanoid skeleton and said in Russian, “Clarechick! You see? What a good swimmer! Look at the ideal proportion of the hands to the torso.”

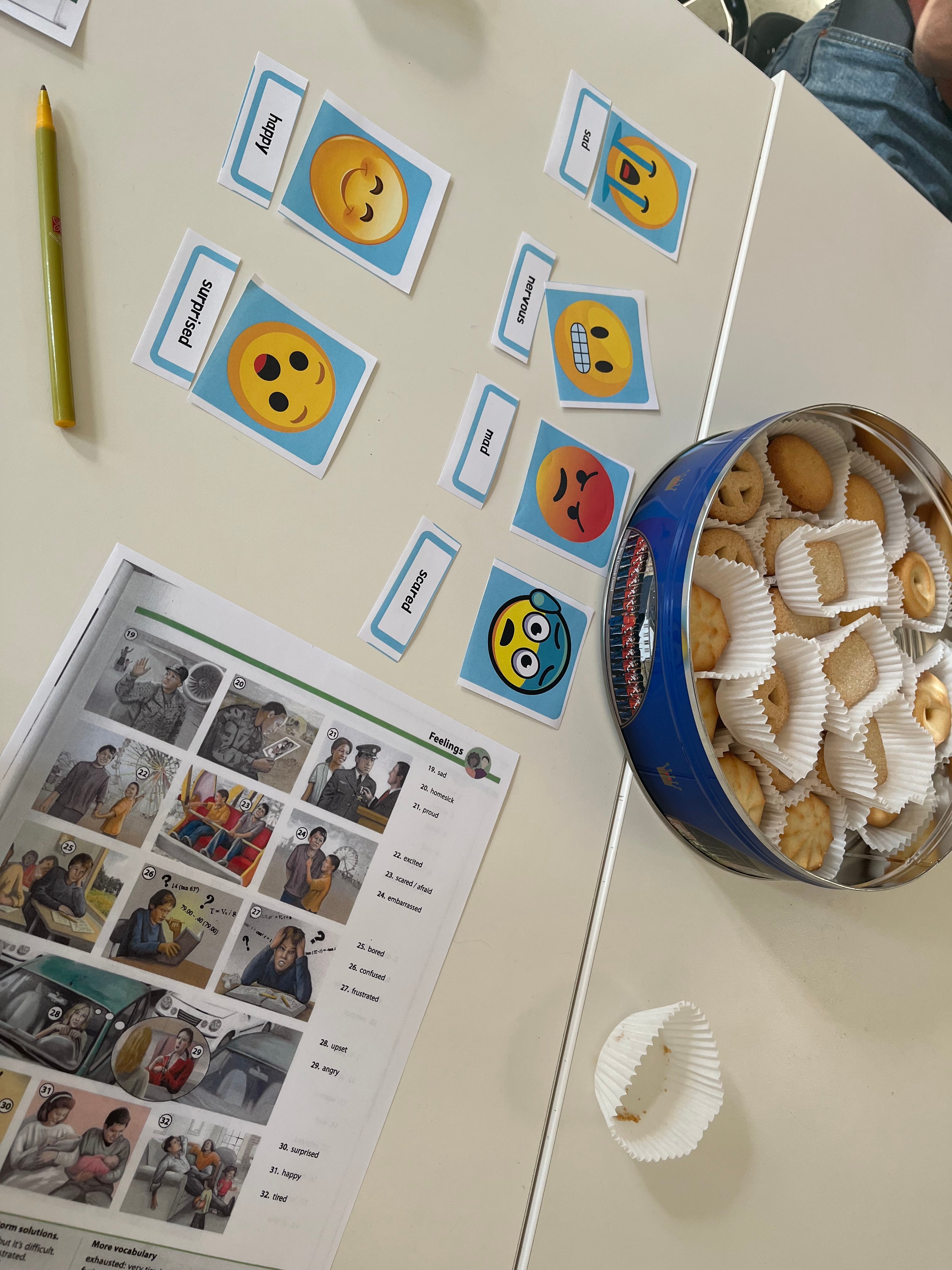

The following Friday was the one-year anniversary of the war. I met Katya and Dima outside the Tompkins Square Library, where Razom, a Ukrainian nonprofit organization, had advertised an event for coffee, conversation and English lessons. I thought it might be a good way for them to meet other recent transplants from Ukraine in a similar position. We entered the library classroom on the top floor. At the table were two other women from Ukraine, and two teachers standing by a whiteboard where: “Friday, February 24, 2023. Today is a sad day” was written in blue dry-erase marker.

“Welcome, everyone,” the male teacher — an American from California — said, as we joined the group. “Today we are going to talk about our feelings. First, let’s introduce ourselves.” Going around the table, each attendee said their name and something that they missed about Ukraine. A woman with vibrant red hair missed her job as a high-up official at the nuclear power plant in Kyiv, and worried that the plant would break down again. Another woman said that she missed her family, friends, and apartment, all of which are now “in the clouds.”

“Hello, I Dima,” said Dima. “My mother professional swimmer for Soviet Union.” He added that he missed his close friends in Kyiv, who he’d known since university.

Katya then stated hesitantly in English, “Hello. I Kateryna. I miss my cat.”

“We are so happy to have you here,” the female teacher — also an American, this time from the Midwest — told the class. “Could you teach us something in Ukrainian?”

Everyone at the table looked around at each other and laughed.

“No one here speak,” Dima explained. “Not all Ukraine speak Ukrainian.” Ukrainian has more in common with Polish and Czech than Russian, and it isn’t spoken by everyone in Ukraine. Since western Ukraine used to be a part of Poland and Austria, Ukrainian is more widely spoken in the west; in Odessa and eastern Ukraine, there are closer historical and linguistic ties with Russia. The school that I worked for in Kyiv had encouraged ex-pat teachers to study Russian, as they thought it would be more useful for us when we traveled outside of Ukraine to other former republics such as Lithuania, Estonia, or Georgia.

After we wrapped up with Razom, I took Katya and Dima to Veselka, a Ukrainian restaurant in the East Village, where we ordered borscht, pierogies, and potato pancakes.

“I forgot how good food is from home,” Dima proclaimed as he slurped borscht and wolfed down meat and potato dumplings. “In Germany, I just ate ramen. From box.”

Later, we went to another Ukrainian refugee-friendly event that had been advertised in Razom’s recent emails. I was surprised to recognize someone I’d met at a New Year’s party in Kyiv back in 2017. After the event, I approached him and learned that he’d moved to New York before the war, and was now working as a videographer in the city. I introduced him to Katya and Dima, and told him I’d send him a message on Facebook.

The next day, I met Katya and Dima at the Holy Trinity Cathedral Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the East Village. Handing over her Ukrainian passport, Katya registered herself with Razom, providing her email, phone, and WhatsApp number so that she could be added to their email registry, and receive assistance with her future needs. I walked with her over to the large table where volunteers were passing out bags of carrots, onions, potatoes, and other food products, while other refugees dug through piles of used clothing, shoes, household goods, and hygiene products. The walls of the room were decorated with images of the Ukrainian national poet, Taras Shevchenko, and icons of saints.

“A sweet for someone sweet,” Katya told me in Russian, as she handed me a Roshen hazelnut chocolate bar she’d found in the donation box. I passed it back to her. “Net,” she said, opening my backpack and zipping it inside alongside the photocopied handouts from Razom which provided information on home health aid training, security guard positions, construction work, legal counsel and information on English classes.

Dima had loitered outside the church when Katya and I went in, and now I went outside to locate him so that he could undergo his US-mandated tuberculosis testing and receive the flu vaccine. Dima was standing outside of the cathedral with crossed arms. “Clare, I not go in,” he said.“This church.”

“Dima, you have to go get registered,” I explained.

“This for people who have nothing. I have home. I not go to church,” Dima retorted.

Exasperated, I went to find Katya. She was inside, chatting with another refugee about finding work.

“Katya, did Dima have a bad experience with the Orthodox church?” I asked. She nodded but didn’t say anything more. I could only guess what Dima’s experiences were. Many of my other Ukrainian friends had been outraged by the corrupt mishandling of tithes in the Orthodox church. It was known throughout Ukraine, too, that the KGB had used churches to spy on parishioners. Because Ukraine is technically an Orthodox country, the line between church and state is blurry at best, and churches are likely to be seen as an unfriendly extension of the state, especially by younger people. Thinking about it that way, I could understand Dima’s reticence.

“Let’s go to a café. Get some coffee, and take a break Clarechick,” Katya said. I nodded in agreement.

Seated at a cozy table in a local café, I explained to Dima, “This event is sponsored by the city of New York and Razom. The city has used different churches, synagogues, libraries, and other buildings since the 1900’s as community centers for newly arrived immigrants such as the Irish, Italians, and Polish.”

“I sorry, Clare,” Dima said, “Twenty-six years of thinking one way, forgive me. Coming to America is my dream.” I could only imagine what it would be like to grow up in a country recovering from decades of generational traumas such as the genocide of the Ukrainian people by forced starvation in the Holodomor, the collectivization of farmland, or the oppression of their national language and culture throughout the Soviet regime.

“It’s okay. I understand,” I said. “This is New York. Not Ukraine. Here we have separation of church and state. Don’t worry. I checked. It’s city officials in the back. I got you.”

We returned to the cathedral, and Dima dutifully signed himself up for the flu vaccine and the TB test.

**

Katya and Dima’s first few weeks in America were complicated by the fact of Dima’s diabetes. Navigating the US healthcare system is complicated at the best of times — but throwing rapid immigration into the mix made it even more so.

“Clare, help me buy test strips. For sugar,” Dima said to me when he arrived. “I need for testing. We going to medical center soon?”

“Yes,” I said. “We have to wait for your medical insurance cards to come.” I was thankful that he had brought six to seven weeks’ worth of insulin with him to the United States, because I knew from experience that it could take four to six weeks to be fully enrolled in Medicaid. Thankfully, for Katya and Dima, it took them a week to be enrolled, and about two weeks to receive their medical insurance cards.

One reason why I believed New York would be such a good fit for Katya and Dima was because I knew that they would be eligible for the same Medicaid program I was enrolled in. In other parts of the states, access to insulin would be complicated, prohibitively expensive or both. But it wasn’t exactly simple in New York, either.

After navigating the 42-page NY and NJ sponsor handbook, I’d figured out how to set up bank accounts, find English classes and locate an affordable fitness centers that had an adequately sized pool for lap swimming. Now, I went back to it to work out how to schedule medical appointments for new arrivals. The answer wasn’t straightforward, so I also asked Razom, who directed me to a Coney Island hospital. I was then rerouted by the hospital to the Customer Service Department, then Primary Care, then to NYC-4NYC, where an hour-long phone call was needed to eventually schedule an emergency medical appointment for Dima in Elmhurst.

The following morning, I made the hour-long trek from my apartment in the Upper West Side to Elmhurst Medical Center to accompany Dima. At 8 o’clock in the morning, lines of patients were wrapped around the corridors and waiting rooms. People were frantically checking in at kiosks, pleading with hospital staff, and impatiently sitting and standing waiting to be seen by a doctor.

“Where are you?” I called Dima as I stood in line at the Primary Care office.

“We coming. We at entrance,” he added.

“Which entrance?” I asked, “There’s so many.” I made my way back through the throngs of people filling the labyrinthine hallways. I finally spotted Dima’s green jacket. “This way,” I gestured, as they dutifully followed me back through the waves of people.

After an hour of standing in line, Dima and I were able to check in with a receptionist. She impatiently typed on her keyboard frowning. “They did this all wrong!” she complained. Even Dima’s name had been spelled wrong on his new medical records. Twenty minutes later, she looked up and handed us a slip of paper. “You need to go here. To Diagnostics. I’ve rescheduled your appointment.” We returned to the sea of people and drifted to a new part of the hospital.

Three further hours of waiting passed. By the time Dima had had his vitals taken, seen a doctor, and had his blood drawn, I checked my watch and realized we’d been at the facility for five hours. And when we finally left, script in hand, we arrived at a local pharmacy and were told that the doctor had written Dima up for the wrong kind of insulin and forgotten to send any filling instructions. The prescription we’d spent all day procuring was useless.

“I’m sorry,” I told Dima, defeated. We would try again at Mount Sinai the next day. I was absolutely horrified by the claustrophobic conditions in Elmhurst, even though I knew that the staff was doing their absolute best to meet their patients’ needs. Compared to Kyiv, where I could go and see a specialist without needing a referral or prior authorization, this was chaos. I missed the beautiful private clinics in Ukraine, and the quiet, dignified public hospitals which provided excellent individualized care.

At the end of their first month in the States, I asked Katya and Dima what their impressions of the country were now they’d spent some time living here. What was better in Ukraine, I asked, and what was better in the US?

Katya quickly responded in Russian that the “people, dynamics,” and “atmosphere” are better in New York — but she misses the “parks, evenings in Kyiv, and [affordable] taxis” back home.

Dima thought a little while longer before responding. He said he liked the “scale and possibilities” in New York, and that “the buildings are very impressive”. Additionally, he said, he appreciates “the care of people about each other and maximum support for everyone who needs it” in America.

When he thinks of Kyiv, he said, he misses the “beautiful parks, each with its own history,” the picturesque underground system, and the greenery in general. He showed me a YouTube video showcasing the vibrant vermillion hues of the chestnut trees which line the city’s streets, before finally adding to his list: “Very beautiful girls in Kyiv.”