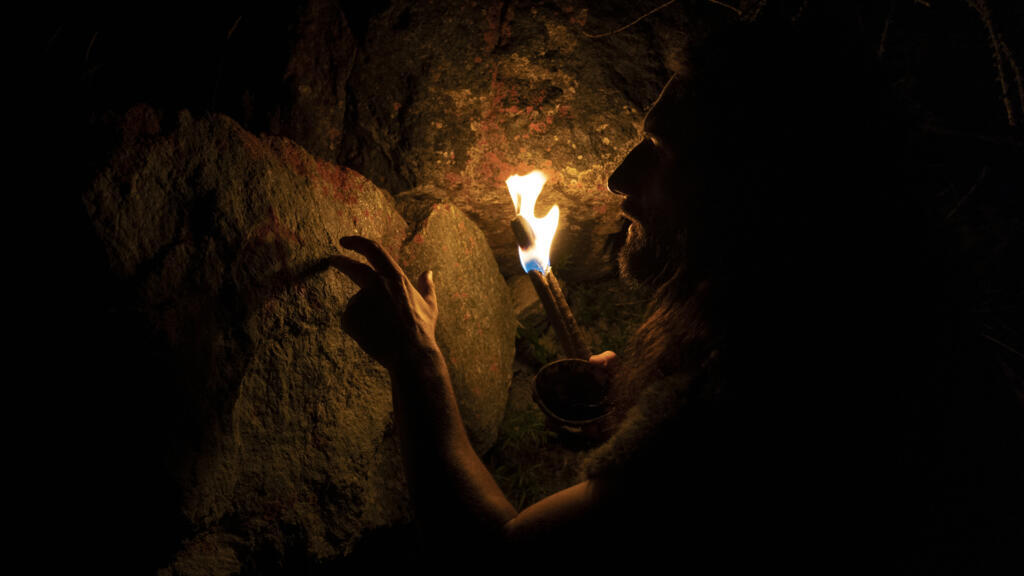

Scientists in Britain say new evidence suggests ancient humans may have mastered the art of making fire far earlier than previously believed.

New research suggests deliberate fire-setting took place in what is now eastern England around 400,000 years ago, pushing back the earliest known date for controlled fire-making by roughly 350,000 years.

Until now, the oldest confirmed evidence had come from Neanderthal sites in northern France dating to about 50,000 years ago.

The findings, published in the journal Nature, centre on the Paleolithic site of Barnham in Suffolk, which has been excavated intermittently for decades.

A team led by the British Museum identified a distinctive patch of baked clay, flint hand axes fractured by extreme heat, and two fragments of iron pyrite – a mineral that produces sparks when struck against flint.

Together, the clues point to deliberate, controlled fire-making rather than a chance blaze.

French cave findings suggest Europe’s first Homo sapiens arrived earlier than thought

A hearth, not a wildfire

Researchers spent four years subjecting the site to detailed analysis to rule out the possibility of natural wildfires. Geochemical tests showed temperatures had exceeded 700 degrees Celsius, with signs of repeated burning in the same location over time.

That pattern, the scientists say, is far more consistent with a constructed hearth than a lightning strike.

Rob Davis, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the British Museum, said the combination of high temperatures, controlled burning and pyrite fragments together show “how they were actually making the fire and the fact they were making it”.

Crucially, iron pyrite does not occur naturally at Barnham. Its presence suggests the people who lived there deliberately collected it, understanding its properties and how it could be used to ignite tinder.

Such evidence is rare, as deliberate fire-making is seldom preserved in the archaeological record: ash disperses easily, charcoal decays and heat-altered sediments are often eroded over time.

At Barnham, however, the burned deposits were sealed within ancient pond sediments, allowing scientists to reconstruct how early humans used the site.

Nick Ashton, curator of Paleolithic collections at the British Museum, called it “the most exciting discovery of my long 40-year career”.

Oldest known Neanderthal engravings found in French cave

Evolutionary progress

Fire had significant consequences for early populations, allowing them to survive colder climates, deter predators and cook food.

Chris Stringer, a human evolution specialist at the UK's Natural History Museum, said fossils from Britain and Spain suggest the inhabitants of Barnham were early Neanderthals. Their cranial features and DNA, he noted, point to growing cognitive and technological sophistication at this stage in human evolution.

Archaeologists say the Barnham site fits into a wider pattern seen across Britain and continental Europe between 500,000 and 400,000 years ago.

During this period, brain size in early humans began to approach modern levels, while evidence for increasingly complex behaviour becomes more visible in the archaeological record.

(with newswires)