Last year alone, human activities — such as burning coal for cheap power — led to our planet warming by 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.34 Fahrenheit), according to a new report. If we continue pumping heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at our current rate, scientists say we have about five years before we drive global warming beyond the 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) set by the Paris Agreement.

Once again, the findings show that human-driven global warming continues to heat the planet — and that's even though climate action has somewhat slowed the overall rise in greenhouse gas emissions. "Global temperatures are still heading in the wrong direction and faster than ever before," Piers Forster, who is a climate scientist at the University of Leeds in the U.K., said in a statement provided by the university, whose scientists spearheaded the new report.

Related: Scientists are mapping Earth's rivers from space before climate change devastates our planet

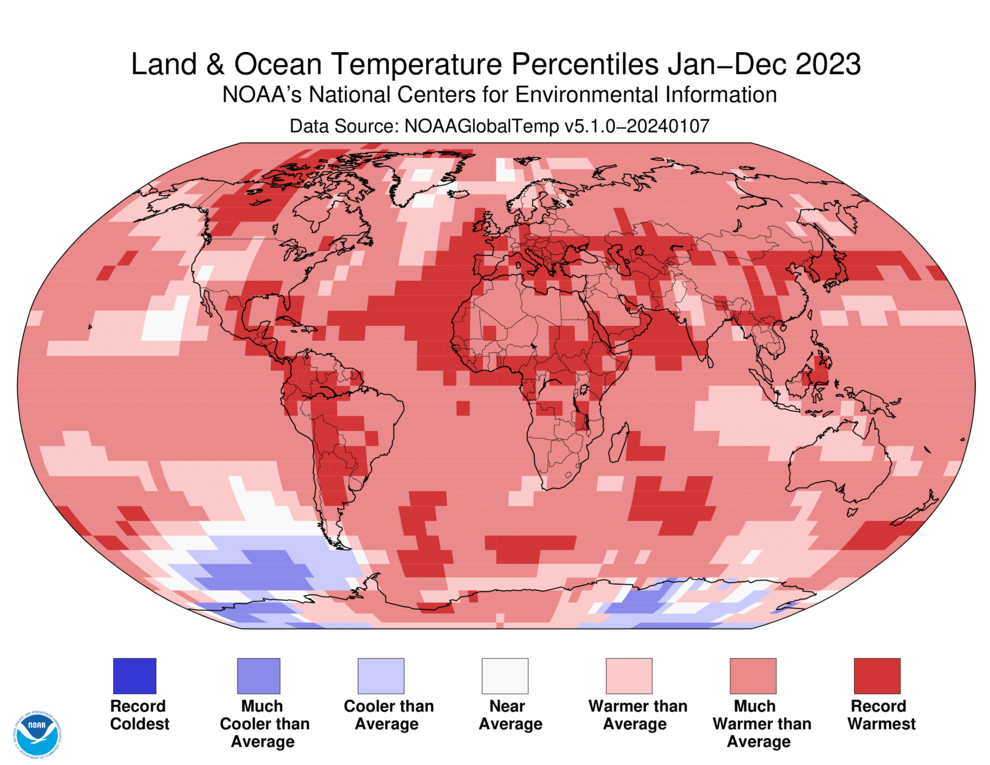

Last year, from June through December, each month set a global heat record for its respective history. For example, July 2023 was the hottest July on a record that dates back to the late 1800s. Those extreme temperatures devastated many regions across the world, thawing Antarctic ice to unmatched lows and sparking the worst-ever wildfire season in Canada. The extreme heat was clearly driven by heat-trapping gases emitted when companies burn fossil fuels to generate power.

These record-shattering temperatures were further exacerbated by a recurring weather pattern known as El Niño, which is linked to warmer temperatures on average, although scientists say it has been strengthening over the past 60 years due to global warming. And, again, human activities are the primary driver of global warming — what we're seeing in terms of climate change, scientists have reiterated, is not a healthy and natural phenomenon for our planet.

"Last year, when observed temperature records were broken, these natural factors were temporarily adding around 10 percent to the long-term warming," Forster said in the news release. "The devastation wrought by wildfires, drought, flooding and heat waves the world saw in 2023 must not become the new normal."

Over the past decade, from 2014 to 2023, temperatures rose by 1.19 degrees Celsius (2.1 Fahrenheit) — an increase from the 1.14 degrees Celsius (2 Fahrenheit) seen from 2013 to 2022, according to the new report, which was published Tuesday (June 4) and overseen by over 50 scientists including Forster. A full version of the report can be viewed in the journal Earth System Science Data.

The scientists say the past decade's global warming is also partly a side effect of reduced sulfur emissions from the commercial shipping industry, which, since 2020, has changed its fuel composition to limit sulfur in accordance with regulations from the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Those regulations aimed at — and were successful in — reducing air pollution from ships. That might sound like a positive, but not in all aspects. Sulfur is known to have a cooling effect on the planet by reflecting sunlight back into space. So, the accelerated phaseout of sulfur in marine fuel starting 2020 meant fewer sulfur particles were in the atmosphere to reflect the sun's rays.

Global warming due to this IMO regulation is equal to tacking on roughly two additional years of greenhouse gas emissions at current rates, which may not fundamentally change where the world is headed in terms of warming by 2050, but "it does make it more difficult to limit warming to 1.5C over the next few decades," Forster and climate scientist Zeke Hausfather at Berkeley Earth wrote in Carbon Brief last year.

The latest findings are also echoed in multiple reports issued this year. In February, the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service announced that, last year, average temperatures worldwide rose by 1.48 degrees Celsius, or 2.66 Fahrenheit, compared to the late 19th century — marking 2023 as the hottest total year on record. An analysis by scientists at NASA similarly concluded last year's global temperatures to be around 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.16 Fahrenheit) warmer than pre-industrial levels.

While every organization employs slightly different methods to arrive at these numbers, they all agree 2023 was our planet's hottest in a century and a half, and possibly in the past 2,000 years.

"It's just so obvious we should do as much as possible, as soon as possible," Jan Esper, a climate scientist at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany, had told reporters during a press briefing last month. "I am worried about global warming — it's one of the biggest threats out there."

This November, world leaders will gather for the United Nations climate conference COP29 in Azerbaijan for the latest round of negotiations aimed at capping the rise of global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to preindustrial levels.