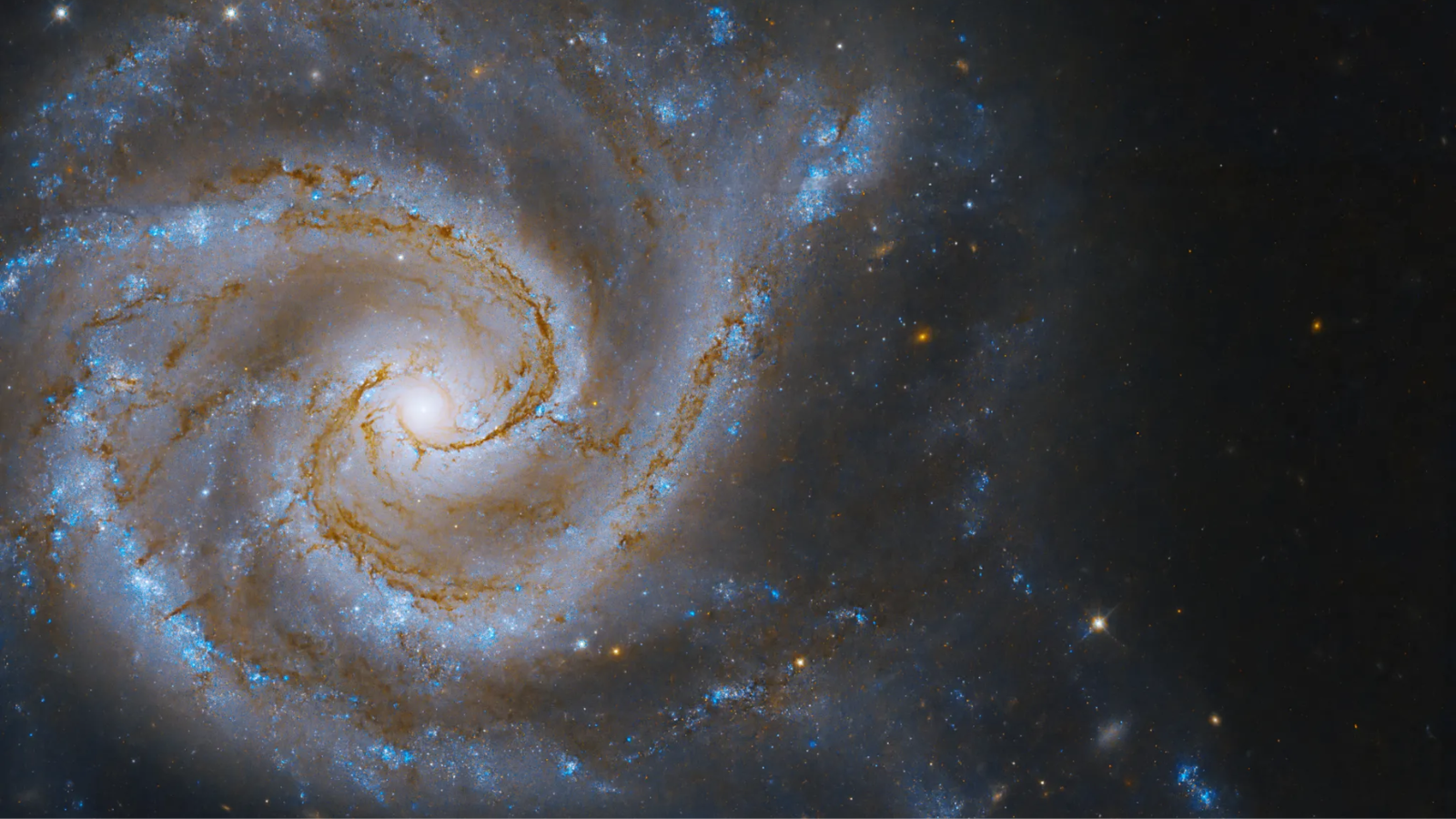

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has zoomed in on one side of a cosmic tug-of-war that will rage between two galaxies for tens of millions of years. Frustratingly, this is one competition in which a clear winner may never emerge, as the two galaxies could well be drawn together to merge into one at the end of this gravitational contest.

The galaxy imaged by Hubble is the spiral galaxy NGC 5427. Along with its opponent, the similarly sized spiral galaxy NGC 5426, the galaxy makes up the pairing Arp 271, located around 130 million light-years from Earth in the constellation of Virgo.

While NGC 5426 is just out of frame in this image, its effects are definitely clear. At the bottom right of the spiral galaxy, a lane of gas, dust, and stars can be seen pulling away from NGC 5427. This is the result of the gravitational attraction between the two bodies, creating the cosmic rope stretching between them.

Related: Hubble Telescope spies massive 'bridge of stars' connecting 2 galaxies on collision course (image)

Referred to together as Arp 271, the two interacting galaxies stretch through space for around 130,000 light-years, which is around 1.3 times the width of our solo galaxy, the Milky Way.

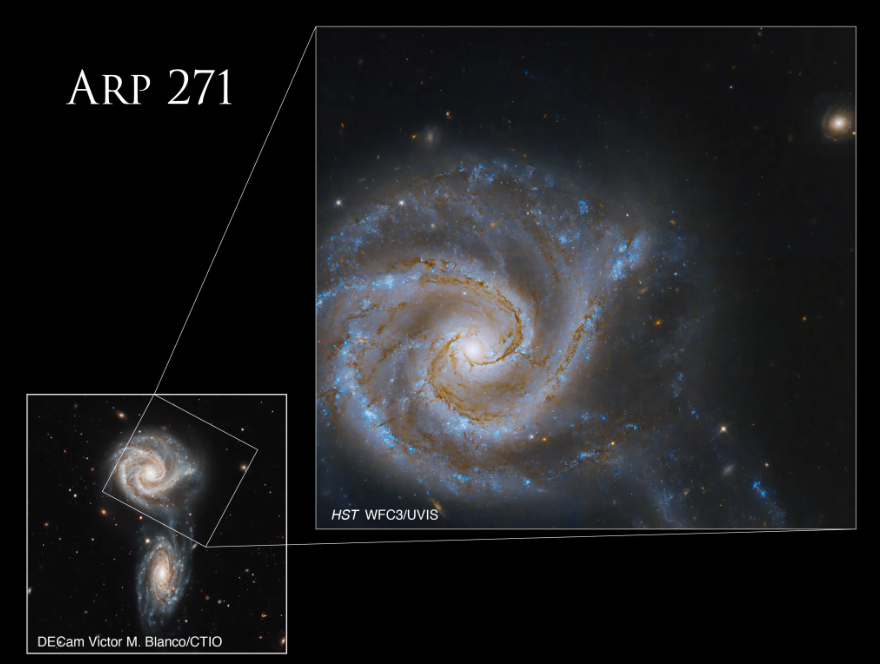

Arp 271 was discovered by British astronomer William Herschel in 1785 and has been widely studied by a range of ground- and space-based telescopes, including the Víctor M. Blanco Telescope, located at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile on the summit of Mount Cerro Tololo.

Blanco offered a full view of this cosmic tug of war between these two galaxies that allows the Hubble image of NGC 5427 to be fully contextualized.

Scientists are certain that this interaction will last for many millions of years to come. What is not clear yet from observations of Arp 271 is whether its gravitational interaction will cause these two galaxies to draw together, collide and merge.

Astronomers can see the gravitational interaction causes gas to be shared between these galaxies, and this is triggering the formation of new stars. Many of these infant stars can be seen in the cosmic 'rope' of gas and dust that stretches between NGC 5427 and NGC 5426.

Observing interacting galaxies gives scientists a snapshot of what will happen when the Milky Way and its neighboring galaxy, Andromeda, move together and collide in the far future.

The two spiral galaxies are approaching each other at a rate of around 671,000 miles per hour (1,079,870 km/h), about 450 times as fast as the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter. But they still have a whopping 2.5 million light-years to traverse before they meet and merge in around 4.5 billion years.

The question is, what becomes of the solar system when this merger occurs?

Scientists simulated the merger between our galaxy and Andromeda in 2006 and found that it may fling the sun and the solar system toward the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

After this, depending on how close our star gets to Sgr A*, two things could happen. If our star gets close enough to the 4.5 million solar mass supermassive black hole, it may be shredded by immense gravitational forces.

Alternatively, if the sun falls into an orbit around Sgr A*, it may be whipped around so rapidly that it is flung from the Milky Way altogether.

By studying interactive galaxies like those in Apr 297, scientists can build better simulations that will show us if the solar system and the sun will meet a grizzly fate or if they are doomed to a lonely existence in which they will wander the universe divided from their home galaxy.