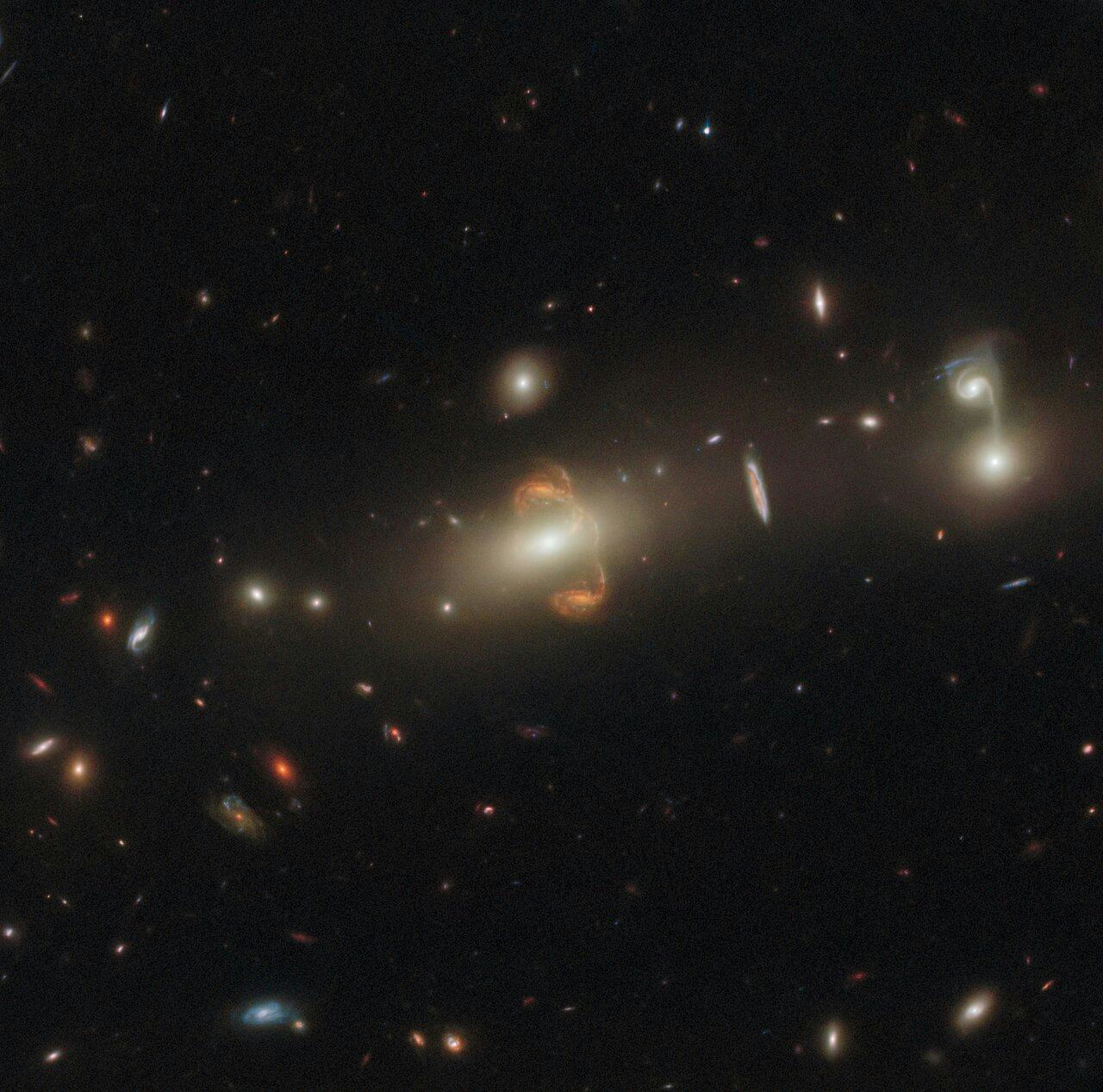

One peculiar galaxy in the Boötes constellation has a lot in common with the sluggish celestial body that enchanted astronomers two weeks ago. Galaxy SGAS J143845+145407 looks like it has a twin next to it in space, but this is actually a visual distortion of epic proportions.

In a newly-published Hubble Space Telescope image, a hefty collection of mass can be seen contorting the galaxy’s light to create a sort of space mirror. This effect is called gravitational lensing, and it’s this phenomenon that also stretched the light from some galaxies in the James Webb Space Telescope’s First Deep Field image announced by President Biden on July 11. The bent light caused some galaxies to appear like the slimy gastropods that come out after a rain shower.

“Gravitational lensing can result in multiple images of the original galaxy, as seen in this image,” the Hubble team wrote in an image description published by the European Space Agency (ESA) on July 18, and later by NASA on July 22. “Hubble was the first telescope to resolve details within lensed images of galaxies and is capable of imaging both their shape and internal structure.”

“Hubble has been used in an unexpected way for us, to look at nature’s magnifying glass — these gravitational lenses,” Jennifer Wiseman, senior project scientist for Hubble, says in a NASA video published last year.

The stars in galaxies emit light in all directions in space, and usually, telescopes pick up just the light that is coming straight towards Earth. Concentrations of mass, such as heavy stars and pockets of invisible dark matter, contain enough gravity to bend space-time. That then warps the light traveling along that medium, which causes a manipulated view of these objects to reach astronomical instruments like Hubble.

In the case of this Hubble image, gravitational lensing has essentially duplicated the object.

There are other ways that the cosmos gets skewed. Sometimes gravitational lensing produces what’s known as Einstein rings, named after the famous physicist whose general theory of relativity suggested the idea that massive objects could cause the deflection of starlight. Other times, objects like the galactic cluster at the center of Webb’s First Deep Field cause the magnifying glass effect, making distant objects more visible.

This trick helps astronomers learn more about dark matter’s presence, Wiseman noted. Astronomers think dark matter makes up 80 percent of the mass of the Universe.

ESA officials further elaborated on the scientific value of SGAS J143845+145407.

“This particular lensed galaxy is from a set of Hubble observations that take advantage of gravitational lensing to peer inside galaxies in the early universe,” they write. “The lensing reveals details that allow astronomers to better understand star formation in early galaxies, which gives scientists insight into how the overall evolution of galaxies unfolded.”

Hubble is still surveying the Universe after more than three decades, and it will continue to work in tandem with the next-generation JWST to use these eccentric visual deceptions as a way of learning about the cosmos.