Writing about the dead is difficult business. Whenever I write about my mother, I spend a lot of time struggling to recall: How did she take her coffee? What music made her dance? When she laughed, did she throw her head back, like I do? My ability to answer these questions—to try to create an honest portrait of her on the page—is constrained by the five and a half years we spent together before she died. To fill in the gaps, I’ve interviewed family and friends, even built an archive of documents and photos. Each piece of new information—her U.S. naturalization certificate, her honeymoon pictures—is a gift, but it’s also a reminder of all that I will never know about her.

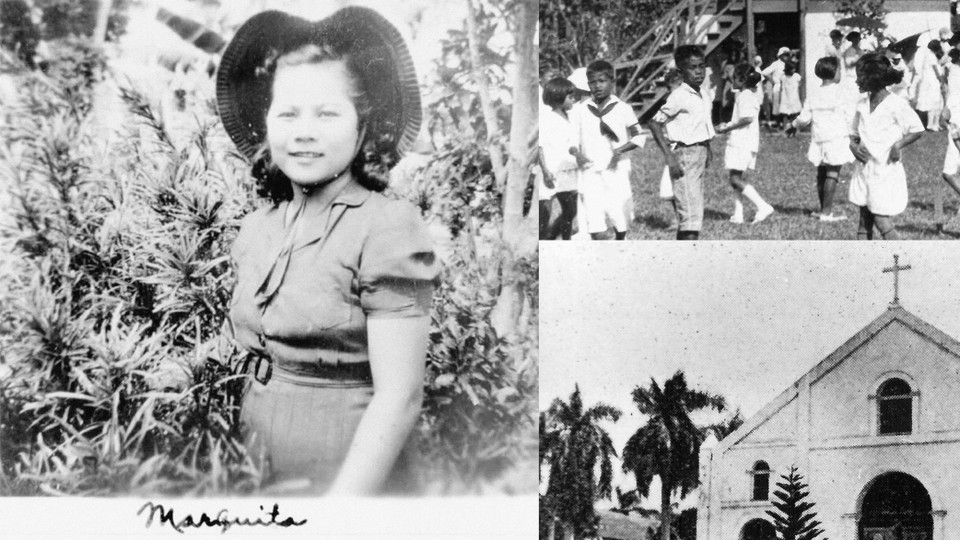

Given how intense and emotional the work of remembering can be, I was stunned to learn the story behind a book called Mariquita: A Tragedy of Guam. First published 40 years ago by the journalist Chris Perez Howard, it’s considered to be the most widely read contemporary text from the often overlooked U.S. territory of Guam, where my family is from. Part novel and part biography, Mariquita follows the author’s Indigenous Chamorro mother, who was killed when he was a small boy during the World War II occupation of Guam by the Japanese. She died just three days before American troops arrived; her body was never found.

In some ways, Mariquita is the story of all Pacific Islanders whose lives have been shattered by the wars of empire, the surviving generations left to make sense of the ruins. Although my own mother was born in Okinawa, as a young girl she moved to Guam. There, she met my Chamorro father, whose parents had lived through the war. I first learned of the occupation during the years I lived on the island as a child, but I just as quickly learned that most manåmko’, or elders, didn’t like to talk about that time. Better to leave old wounds alone. This was the silence—the pain—that Perez Howard had to confront in order to write Mariquita. As an adult with limited connection to his homeland and few memories of his mother, he set out to learn about her. It was in piecing together the details of her short life that he resurrected her.

[Read: When the U.S. military came to Guam]

Perez Howard grew up knowing only the basic facts of his earliest years, though this was enough to justify his use of the word tragedy in the book’s subtitle. He was born on Guam in 1940 to Maria “Mariquita” Aguon Perez and Edward Neal Howard, an American sailor who was stationed on Guam aboard the U.S.S. Penguin when the Imperial Japanese army invaded in December 1941. The elder Howard was captured as a prisoner of war and sent to Japan; back on Guam, his wife, young son and daughter, and thousands of Chamorros endured 31 months of what the historian Robert F. Rogers called “a vigil of courageous despair.” In the summer of 1944, once when it became clear that Japan’s cause was doomed, the violence against the local people escalated: labor camps, rapes, death marches, massacres. Mariquita, who’d been forced to work as a personal servant to a Japanese officer, was last seen being severely beaten and then taken into the jungle. After Japan’s defeat, Howard tried but couldn’t locate his wife’s body; he moved to the United States with both of his children, who were now motherless.

Although this extraordinary summary reflects the book’s main arc, it doesn’t capture what I find most moving about Mariquita. No—for me, the deeper meaning comes from Perez Howard’s return to Guam in 1979. In the prologue to a revised 2019 edition of the novel, Perez Howard writes of being perturbed by how family and friends welcomed him back to the island by sharing their memories of his mother, who had been pretty, petite, lively, and well-loved. “Everyone seemed to know something about her, except for me, her son,” he writes—a relatable sentiment for anyone who has lost a parent at a young age. His mother’s death haunted him, but so did the mystery of her life. Who was Mariquita? Like any good journalist, he decided to report it out. He pored over university and library archives, conducted oral interviews with other war survivors, and pressed relatives for the smallest of details: the kinds of dresses his mother wore, where she and her girlfriends liked to hang out on weekends.

As a result, even though Mariquita is frequently described as a novel, it’s more accurately a work of fictionalized, yet heavily researched, biography. It is also an illuminating, emotional, and at times disorienting read. The genre and tone are in constant flux. Mariquita jumps between romance (when tracing Edward and Mariquita’s courtship), textbook (as it explains Guam’s colonial past), soap opera (during the sometimes-maudlin invented dialogue), and action thriller (providing an account of the fall of Guam). “Out beyond the reef were several ghost-looking ships, and flares were lighting the sky,” Perez Howard writes of his family’s experience of the Japanese invasion. “As they stood there, transfixed by the incredible sight, the menacing sound of gunfire came from a distance.” The narrator’s voice shifts, too, never quite settling on one perspective. Sometimes, the speaker seems matter-of-fact and detached; at other times, the reader enters Mariquita’s mind and the minds of other characters. Of the taichō, or Japanese officer, whom Mariquita worked for: “He wanted Mariquita to submit willingly to his superiority, and sex would be the ultimate proof of this submission.” Of Mariquita: “She had thought of running away, but surely, she would have been killed when caught.”

Where some readers might see a frustrating lack of cohesion, I see authentic fragmentation and disorder. At 113 pages, the book is too slim to be everything its author wanted it to be: family saga, war novel, love letter, historical text, anti-imperial cri de coeur. But Perez Howard’s attempt to capture all of these moods and points of view only reinforces the unspeakable complexity of these wartime years for Chamorros.

The somewhat underdeveloped quality of the original novel was due in part to the lack of literary resources on the island at the time of publication. In the ’80s, Guam had no infrastructure for producing books. Determined to publish it locally, Perez Howard enlisted a local printer and typist; as a result, the first run of 100 copies featured rampant typos and poor binding. Eventually, the story found an audience; it was published in Japan and then by the University of the South Pacific in 1986, making it “one of the first contemporary Chamorro literary texts to circulate beyond the Marianas archipelago,” according to the Chamorro scholar and poet Craig Santos Perez. “Much of Chamorro literature … is unpublished, archived, and out-of-print; or, if it is published, it has not circulated widely,” Santos Perez notes. As a result, Mariquita is a significant entry in the context of both Pacific literature and, given Guam’s status as a modern-day American colony, U.S. literature.

Today, following centuries of rule and suppression by the Spanish, Japanese, and Americans, the Chamorro language has fewer than 50,000 native speakers. My grandfather Antonio used to teach Chamorro to schoolchildren, although I never learned it myself. Still, oral tradition remains a core part of the culture. The stories my grandparents told me as a child—of the mermaid Sirena, of the brother-and-sister creation gods Puntan and Fu’una, of the taotaomona spirits—are my inheritance. But growing up, I didn’t know that books by Chamorro writers existed, and I’d certainly never heard of Mariquita. Reading it as an adult—particularly one interested in questions of grief, memory, and heritage—felt like stumbling across a secret. Yet these kinds of stories shouldn’t be secrets or mere footnotes in literary history. It is possible for dispossessed people to participate in their own history, to make art that captures their singular experiences, and to resurrect their loved ones.

At its core, Mariquita is a gravestone made of ink on paper, built by a son for his mother. Some of the most heartbreaking passages are the ones in which Perez Howard describes his younger self in the third person.“The months passed and it was almost Chris’s first birthday,” he writes about himself. “He was a good child, who rarely fussed, and the contentment in his dark eyes reflected all the love he was given. The happiness he gave Mariquita was such that she seldom left him.” This is that difficult business of writing about the dead; emotions surface out of nowhere, leaving you reeling for days.

[Read: I didn’t know my mom was dying. Then she was gone. ]

Perez Howard understood this. In the afterword to the updated edition of the book, he describes how the process of researching and writing the book changed him. “At the beginning, it was easy to write about her because I was writing about someone I didn’t know,” Perez Howard recalls. But over the course of working on the book, he grew to love her—a realization that caused him to break down at one point as he was nearing the completion of his manuscript. “I may not have remembered her in the ordinary sense, but I had a deeply rooted memory of her and I was reminded that day about how much I loved her and missed her,” he writes.

When I read those lines, I cried. I knew what he meant. You write in order to make sense and to remember—and at some point, the ground tilts, the page vanishes, text becomes flesh, and she is there again, like she never left. Alive and yours.