Minda Honey opens her memoir, "The Heartbreak Years," by taking us back to 2008, "a time before Tinder, before Uber, before Amazon same-day delivery." She was 23 and living in Cincinnati, Ohio, where she had just been sabotaged out of her first post-college corporate job by a racist boss, when she drove both the car and the boyfriend she'd had since high school across the country to Orange County, California, to house-sit for his grandparents. Her boyfriend had a dream to pursue there and, as she writes, she "was just content to flee the cold."

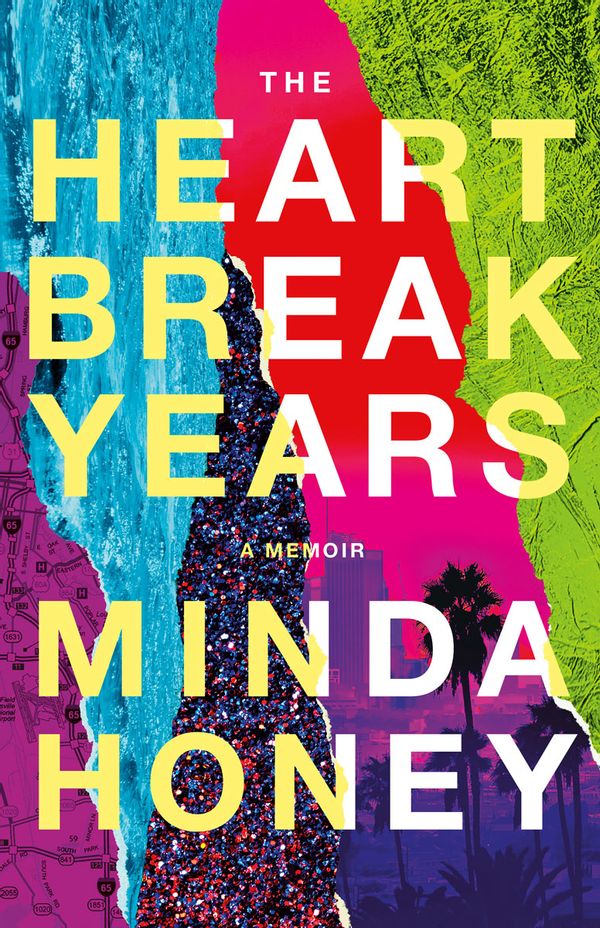

The relationship didn't last, but Honey stayed in California for several years, with a detour in Denver, before returning home to Louisville, Kentucky, where she lives today. In this sparkling debut, Honey — editor of Black Joy at Reckon News, erstwhile advice columnist and media entrepreneur, and former director of the BFA in Creative Writing program at Spalding University, where I also teach — chronicles with generous humor and self-awareness the highs and lows of partying, hooking up, dating and breaking up with a series of memorable young men in Obama-era Southern California, while also trying on a series of professional identities before she committed to her writing career.

Honey writes about her younger self with clarity and empathy, as a Black millennial woman whose pursuit of a relationship was, in her 20s, equally informed by the romance stories she grew up with and the wider media and cultural messages that warned her, "Single women aren't taken seriously. Men are allowed to live their fullest lives before settling down, but a woman's life doesn't begin until she settles down."

I sat down with Honey recently at Trouble Bar in Louisville, where she has a cocktail named after her (order the Storyteller with or without the booze), to talk about memoir writing, her best advice for young single people, and what people — especially people in blue states — get wrong about the South.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

I was always taught to "write for your best reader," and you were probably taught this too. Who is that for you? Who did you write this memoir for?

I'm writing it for my present-day self, and women like me whose lives have not followed the traditional path, because it can feel very lonely. You know, we're in the South, we're in the Bible Belt. So sometimes I feel like I'm literally the only person who's not married with children. So I want people to know they're not alone in this. And then I'm also writing it for those folks who are in their early and mid-20s, and they're feeling kind of lost, and things are very uncertain. You can do this; you're going to come out on the other side of this just fine.

A few years ago, I remember I was on the phone with a friend who's [about] eight years younger than me, and she had moved to a new city to be with a boyfriend who then broke up with her and told her she had to go back home. And I said, no, no, he can break up with you if he wants to. But you can decide if you go back. And then I [thought], why am I so passionate about this? Oh, wait, I learned this. I did this. And I have a friend right now who's going through something kind of similar. It can be scary.

I think this book is for those folks. If you've endured a heartbreak, and you've had to decide whether or not you're going to go back home on your own terms; if you've ever had a rocky workplace situation — because that was also a subtle thread through the book.

I really appreciated that as well. The book opens with this great line. "2008: Great year for Obama, trash year for Minda." You're 23, you moved cross country with your high school sweetheart to Southern California. Can you walk us through — for anybody who wasn't dating in the mid-Aughts — how different it was then?

I guess that's a little hard to say. Southern California's culture is so different from the South. And so in some ways, even though it's the same timeline — we were all living in 2008 — to go from the South to Southern California was almost like time traveling because there was this drastically different dating culture.

In Louisville, I knew plenty of people who were with their high school sweethearts, or their college sweethearts, who were very young and in these long-term relationships, or living with partners very early on and having every intent of marrying this person, having children, settling down. That was the vision. So when I moved to California, suddenly all my new friends were becoming single right around the same time that all of my Kentucky friends were getting married and having babies and buying houses. It was this totally different world. I felt like I [had been] dropped down in the middle of the movie. Everyone else had already been dabbling in online dating and engaging in hookup culture and doing all these things. And I was like, Oh, I'm late to the party here. I gotta play catch up.

The book scenes take place mostly in Southern California, a stint in Denver. Your story isn't the typical, "moved to LA to make it in the industry" narrative. But it's also not a "dark side of the City of Angels" gritty tale of how people come to California to chase their dreams and then they die. Those are two types of Southern California books I've read versions of. What kind of California story were you interested in telling in this book?

For me, California was just someplace I ended up. I moved to Orange County because that's where my ex's grandparents' house was. I talk about this in the book — he was following his dance dreams, and I was just trying to figure out what to do next after quitting my job. So I didn't ever really have any ambitions of "making it big in the big city." At some point, after I'd been in Orange County for a few years, I took a job that moved me up to LA. I would say probably for almost the first week that I was in my LA apartment, I was so overwhelmed — by the city, the traffic, all the people. I felt like I'd done so much more than move an hour north. It was pretty overwhelming. So because of that I was just doing pretty typical, standard 20-something things, like making friends, going on dates, going out to parties, and LA just happened to be the backdrop for that.

I do think that it makes a difference — this book wasn't taking place in Chicago or New York — because we're contending with all of the stereotypes about LA. You know, all the beauty and the vanity and the [assumption that] nobody wants to settle down until they're 45. All of those things are at play too.

And like you said, because I wasn't — I mean, per my Amazon reviewers, I did a lot of drinking, I had a lot of sex. [Laughs.] But I wasn't doing drugs. Like you said, I wasn't part of the gritty dark scene of the city. I wasn't trying to become an actress. I was a mop bucket salesman in LA. So in these different ways, I was also undermining the stereotype of what it is to be in LA.

Speaking of stereotypes, we're sitting in what a lot of people would consider flyover country, in one of the liberal-ish bubbles of the Bible Belt. What was that like for you, as somebody who grew up here in Louisville, to move away and then come back in your 30s?

Growing up, I would always meet adults who had left Louisville and moved someplace like LA or New York and then moved back, and I was so baffled. I was like, Why would you come back? But I don't know what it is — it's like you're a wind-up doll, and at some point, the switch flips: It's time to go back, I gotta go back to Louisville. And even when I was out West, I came home at least once a year, maybe twice a year. And there was something revitalizing about being back in Louisville, feeling like I wasn't so out of context. All my family's here. My high school friends are here. My college friends are here. It was just something that felt familiar. But to come back in my 30s, you know, that was different because a lot of people had gotten married and had kids, so they were in a very different place in their life than I was when I came back. It also meant that the dating pool was very limited, because everybody was off the market. And now I'm dealing with the divorcees. Maybe that'll be the second book.

The aftermarket.

It's not promising, Erin, it's not promising.

A thing that happens in places where people get married in their early 20s is that a lot of them get divorced in their 30s and 40s. [Disclosure: I did!]

I have no judgment! I have cheered on all of my friends. But the problem dating those men who are newly back on the market is that it's a very short trajectory from you feeling sympathetic for him about, you know, the "awful ex-wife" he had to endure, and all of a sudden being Team Her: You know what? I see what she saw.

To go back to the question about stereotypes, are there misconceptions that you've encountered that people outside of Kentucky or the South have about this region? And does that come up in your writing?

Particularly in this era that I'm covering in the book, there were a lot of political stereotypes that came to mind. You know, we see it all the time. I wrote a piece for Salon about Charles Booker, Mitch McConnell and Daniel Cameron. We get a lot of flak about Mitch McConnell in Kentucky being in power. But y'all — that doesn't happen on just the backs of Kentuckians. Who lines Mitch McConnell's pockets? Kentucky is a very poor state. That man built up that money from donors like you, donors from your state, you know. So all of it is interconnected. And I don't think that in other parts of the country, they realize how much the South undergirds so much of what happens in this country: the relevance, the importance of the South, all of the Civil Rights movements and activists who are coming out of the South who are fighting that fight day in, day out.

And I think they also have this idea that where they live is a utopia. No. I was in California when Prop 8 [banning same-sex marriage in 2008] passed. I experienced racism in California. When you think about George Floyd, that [happened] in a Northern city. Racism is happening everywhere. In the South, it's just a little bit more visible. Somebody's got their Confederate flag waving and it's a lot more evident for me. Maybe I'm not going to go to that convenience store. Whereas in other parts of the country, it can be a lot more about subtext — a lot more reading between the lines, and a lot less surface level with the racism and the violence that you're going to experience.

There is also a thread of workplace and class and economics that is woven through your book that feels just as strong of a throughline to me as the search for a romantic partner, especially coming of age career-wise during the Great Recession. Can you talk about how that thread factored into the story you wanted to tell?

I'm someone who's worked a lot of jobs. I've probably worked over 30 jobs in my life. By the time I was 18, my dad refused to do my taxes anymore, because I would have like seven W-2s a year. I was a big job hopper. I just like knowing how places work. And that means I've experienced a lot of workplace cultures, and interacted with a lot of different kinds of people. And because I graduated in 2007— so, during the Great Recession — there were no jobs. I had a job, and it was a very competitive position. And for this program, I was the only Black person, I was the only person that had not been recruited from a top university. So, as competitive as that was, you don't just stumble into that opportunity, you don't luck into that opportunity, when you're someone who came from a state school in Kentucky, right? I had to have had the credentials, had the skill set necessary to succeed in that role, which is why it was so upsetting to encounter the workplace racism and the kind of manager that I encountered who made me feel like I didn't have what it took.

But I could see that a lot of the people who ended up in these positions were people who came from wealth, who had access in certain ways. And I've started to think about that more and more as I've gotten older. I've been a freelancer, I've been an entrepreneur, I've been a writer. So you can see the way that privilege weaves its way through all of that.

And it also gave me an opportunity to explore my own class privilege. I don't have a family that could subsidize my writing career, but I was definitely able to stay at my mom's house for a year while I hatched my freelance writing career. I was very comfortable — I had a very cozy bed, clean house, full fridge, and not everyone has access to things like that. I also had to think about a lot of the things that I had been taught to prioritize in my career, the ways in which all of those things were classist or xenophobic, and try to step away from that and be less invested in these ideas of success that had been drilled into kids in school during the '90s.

We send these mixed messages, to girls especially. You have to be everything now. You're going to be a straight A-student and gorgeous, and you're going to get that romantic partner — check. Home — check. Family, if you want it — check. But at the same time, I do think that there are a lot of subtle pressures that tell women that you can't be too invested in your career.

Yeah. You've got to be willing to shift your career into second gear to support your partner's career. You have to be willing to move. You have to be willing to prioritize the opportunities that come their way. You have to be willing to take on all the additional household duties with a smile on your face. You have to be willing to have their child at the expense of your career. I touched on this in the book too.

Women have been taught to be more invested in a man's potential than their own. And some of that is because you feel like if I help this person succeed, then I'm going to be in a relationship and have this financially stable life. Because guess what? You make 40 more cents on the dollar than I do. But you're not owed anything.

[In the book] I mentioned "Waiting to Exhale," where a woman puts a man through medical school or raises his kids and then gets left. There isn't that stability there. But if you're a woman who's like, Well, I'm gonna do it for myself, I'm gonna go out on my own, if you fail at that, or you fail to find love, then you get blamed too. That's your fault as well. So yeah, there's no winning.

I read so many Harlequin romance novels as a kid. I love them. They were formulaic, they were predictable, but that brought me comfort. And I thought about the things that create stability, or that give you the impression of stability, like a happily married couple — if they have this love, then that's going to emanate outwards to their children, and there's going to be this stability. You're just buckled in, you're safe, like being wrapped in bubble wrap is to be in love. And so I went through my youth wanting to have this thing that I hadn't seen at home. So [I thought], I'm going to succeed at this. I'm going to create this and then that's what's going to give me the stability and insulate me from all of the unpredictability of volatile relationships.

Unfortunately, you only have control over yourself in a relationship. There's always going to be this other variable. And also, unfortunately, you don't come into the world as a fully emotionally mature adult. And — equally unfortunately — you don't realize that you lack emotional maturity until much, much too late in life. So it wasn't something I was able to achieve. But I think I also learned in the process that it was not a silver bullet, either.

The men in this book were so vividly written. I want to talk about Henry. A lot of men in this book, you know those types. But Henry was a fresh kind of guy for me to read about. At the same time, I feel like the Henry relationship is possibly more common than most people let on. Can you tell us a little bit about his importance to the book?

Chevy and Henry were always going to anchor this book because they anchored my romantic life in my 20s. They were very much two sides of the same coin: Men I could not have a long-term relationship with. It wasn't even a coin, it was like a multi-sided die. I could have played Magic the Gathering, played tabletop role-playing games, with the multi-sided die of my dating life.

Henry, he's such a complex person. And it was such a complicated, complex relationship. It was something that I was able to see differently once I got older, and once our culture shifted a little bit more. In the moment, it was very frustrating to be in a relationship with somebody who was so romantic, and in a lot of ways giving me all the things that I wanted, and did not want to be in a relationship, and did not want to be physical in any type of way. Didn't want to kiss, didn't want to sleep together. And this went on for years, this open-endedness. As I got older, I realized some of what was going on: We just didn't have the language for what Henry and I were in. We were in a romantic platonic relationship.

We weren't talking about asexuality back then, you know. I think people were having a lot of really flat conversations — like accusing men of being gay — but that wouldn't have made our relationship make any more sense. It would still have been equally baffling.

Even though that situation was very frustrating for me, it also brought me a lot of healing. Because there was a romantic component to this friendship. We cuddled, we held hands. I could lean on him. He takes me out on that really sweet date after that man tried to take me to a motel in the middle of the day against my will. And that allowed me to feel safe, you know, to feel like I could express this light physical intimacy with a man and know that he's not going to try to push the boundary — nothing that I don't want to happen will happen. I'm completely safe with this person.

[With Henry] I had almost a sandbox to explore romance in a safe way that I really wish a lot of young people had access to. At one point, I say that wanting is a welcome mat for danger. We have these desires that we're developing as young people and there's not really a lot of safe spaces to explore those. And in a lot of ways, Henry was able to give me that in my 20s. It was really important to include him in the book. One of the notes my editor wrote: I could just read an entire book about you and Henry.

And the cultural trope — again, going back to the rom-com — that we've been taught to expect is eventually the happily ever after should come with the Henry character, right? Here's "a good guy," who's courtly even. In the bad, late-'90s cable version of this story, Minda's sowing her wild oats but eventually realizes he's the one, and then they get married and have babies and whatever. I was pleasantly surprised to find that Henry in this book could help give us a wider vocabulary for talking about what a happy ending really is for Minda, and Henry, separately.

It doesn't have to be a forever story to be a good story. But the other thing that's complicated about Henry was that even though he was very charming and very sweet and romantic, he was just as evasive and dishonest and unwilling to be transparent and vulnerable with me as Chevy, as any of the other men. And that, in its own way, was also very challenging and difficult to deal with. Maybe even more so because it came in such a beautiful package with this big, bright red bow on top. Whereas with some of the other men, it was a lot easier to realize this guy is no good. We can see it from a mile away.

And men, as we're told, are lonely. There's an epidemic of male loneliness, the headlines tell us, and the pundits are saying, essentially, that maybe this is a problem for women to solve. Even if they're not outright saying that, it's between the lines, because the assumption goes also that women have caused the problem because we don't need to marry them in our teens and 20s anymore. I'm curious about what it's like right now to be talking about reflecting on writing about dating in your 20s with men who were emotionally not able to connect intimately with you or anybody else, in the midst of the "men are lonely and here's what we should we all be doing about it" discourse?

You really only have control over yourself, what you bring to a relationship, and what you're willing to accept in a relationship. That's all you can control. I [wrote] about how I was treating Chevy like a Rubik's Cube — he was this puzzle that I could figure out and if I just did this or I did that, then he would love me or he would, you know, want to be with me. You cannot convince someone to be with you. You cannot convince someone to be vulnerable with you. You cannot convince someone to do right by you. You can be vulnerable, you can do right by them. And then you can hope that they're going to do the same thing. And if they aren't, you should probably go. You can decide to stay but what I have learned from personal experiences is you should probably go. You should go right now, you should go very quickly.

We can't change the men. The men have to change themselves. And that's just the reality of it. So I hope that they love themselves and they love the company of us enough to want to do that emotional work, and I guess I will be waiting over here on the sidelines for them to do so.

At one point in the book, there's a scene in a gay club, and this is one of those lines I highlighted: "I wondered why there were no overtly sexual places for straight women calibrated for our comfort." If we could dream for a minute, what would that look like?

What would that look like? I immediately thought of really puffy, plush-like couches. And cutesy clothes — you should be able to show up in your regular everyday clothes and then a fantasy wardrobe you get to change into [appears], and you get to lounge on these puffy couches. There are going to be potential partners that you're interested in, and you should be able to flirt with them, and there should be this general consensus that no one's going to try to take advantage of the fact that you might be interested in them. You should be able to express interest and that does not open you up to danger.

What it would look like is basically the reality that we fake we have when we go to clubs, and we get cute, and we flirt, and we are just putting out of our minds that this is a dangerous situation for us. It would actually be a safe situation. There would be no false illusions of safety. It would just be real.

Aside from the magic of how your dream wardrobe choices appear in front of you — and the dry cleaning issue of the fluffy couches and the drinks — I'm struck by how reasonable and attainable this should be: How about we dream of being able to flirt with people in public and feel safe that no one's going to try to assault us?

And then I can walk home in the dark by myself and think about what a lovely evening I had. And not have to try to be hyper-aware or scared every single moment of it.

This is what women want. Put it in your podcasts, men. You wrote an advice column for several years here in our local alt-weekly, LEO. Do you have a favorite piece of advice that you return to?

Yes. I'm not going to be able to remember it verbatim, but the question was something like, What do you do when you just feel like you're not going to find your forever person? You're tired of looking, you don't think anyone's ever going to want you and you're just sad about it. I told the person, you know, at some point, you just have to face that fear. And you have to ask yourself: OK, so what if I just decide, fine, I'm not going to meet this person? I'm not going to let society bully me into keeping hope alive. I'm just going to call it now: I'm not meeting the person. What life is it that, that you would be living? What choices would you make? What are the things you would spend your time doing instead?

And then guess what? You go and you do all these fulfilling, wonderful things. And if the person does happen to come along, even better. But if they don't, then you're not spending all this time swiping through dating apps endlessly and being in this woe-is-me space. If you just start living as if this is going to be your reality — because the other thing about being in that place and feeling those feelings is that they come in waves, and they recede. So you're not always going to feel like you've lost hope or like you're unwanted. But sometimes you are going to feel that way. And that's OK, too. But the lifeline, the anchor that you can hold on to until those feelings recede, is that I am creating and living a life that I want to create and live.

I think my book started with a few unanswerable questions: Is it me? Will I find him? And what does it say about me if I don't? And I think those questions are unanswerable because the answers to them aren't that important. Oh, can I not find love because I am flawed in some way? You don't need an answer to that question to go off and make yourself a better person. You don't have to think about it in the context of dating and romance to [realize] there's this thing about myself that I'm not comfortable with [so] let me go see a therapist, let me go pick up a hobby. You can do all of those things outside of the context of that question. Same thing with, Will I ever find him? I don't know; life's not a Magic 8 Ball. This book does not end with me finding him. You can't answer that question until the moment it does or doesn't happen.

I read Maggie Smith's memoir, too. And what I really appreciated about it was that she allowed herself to really experience the full range of emotions. And having just written my own memoir, I know how hard that can be, because you don't want to tip over too far in any one direction. You want to give other people grace [and] you want to give yourself grace. You also don't want to water it down too much, either, and be like, Oh, it wasn't that big of a deal. Because it kind of was. You wrote a whole chapter in a book about it. It matters.

That brings me to my final question. Who are you reading these days? What are you excited about?

Oh my gosh, I'm reading so many things right now. Right now I'm so in love with Destiny Hemphill's "Motherworld." It's a poetry collection. The turns of phrase that Destiny is using, the chanting, the themes of mother and nature and our dystopian future that we're heading into, are really incredible. I got an ARC of Ross Gay's new "Book of More Delights," so I'm excited to drop into that. But I also know that I'm going to be going in expecting the light and that he's gonna hit me with the grief. He always does this to us.

Also Airea D. Matthews, I just picked up her book "Bread and Circus." I've been working my way through that. Saidiya Hartman's "Lose Your Mother" — it's about her going to Ghana to try to trace her lineage, and there's this disconnect between, when you're Black in America, all the different things that Africa can represent for you. I went to Senegal last winter, and I'm heading to the Philippines — my mom's Filipino — this winter. So I think my mind is in that space a lot. What is my lineage? How do I create it? Is it possible to follow it? What does it mean? If it isn't, what is it to create your own history out of thin air? I don't know. It's a third book. It's not the next book, but it could be a third book.

I want to be in your book club now.