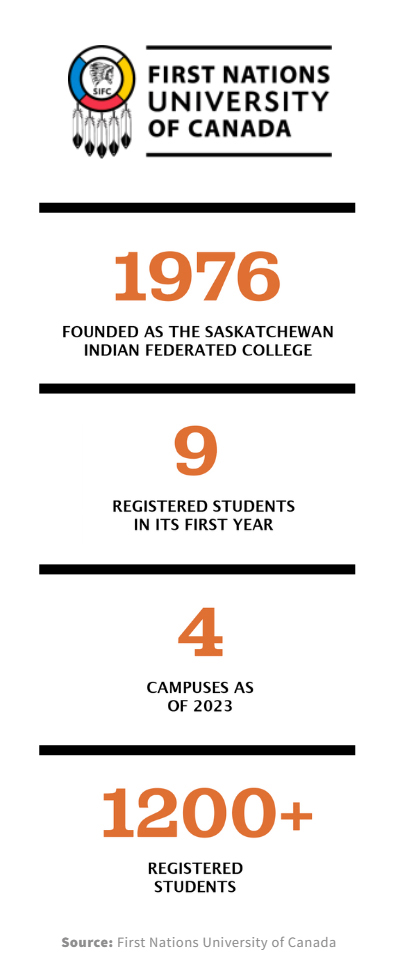

Much has changed in the world of higher learning since 1976, when Saskatchewan Indian Federated College first opened. In its first year, there were just nine students and the programs offered at the college included Indian Studies, Indian Languages, Indian Teacher Education, Social Work, Fine Arts (Indian Art, Indian Art History) and Social Sciences.

In 2003, its name would change to First Nations University of Canada (FNUniv), and now in 2023, programs are offered at four campuses: Regina, Saskatoon, Prince Albert, and on 22 acres butted up against the South Saskatchewan River by the small village of St. Louis for traditional land-based learning.

Beyond the grounds of these campuses, the university now offers programming across the country, including an agreement with Fort Erie Native Friendship Centre, where they certify their Mohawk language programming, community-based programming in Alberta, Northern Ontario, and the Northwest Territories, and online Indigenous programming nationwide through FNUniv’s Indigenous Continuing Education Centre.

One of the most significant changes in post-secondary education today is that awareness of the need to support Indigenous learners better has spread beyond institutions like FNUniv. Post-secondary institutions around the country are working on making the adjustments needed, informed by papers published based on global conversations at the World Higher Education Conference about the need for transformation in higher learning establishments so Indigenous students can thrive.

Global educational leaders have been talking about the need to value Indigenous ways of knowing, learning, and being as equal to colonial knowledge systems, the need to plan for Indigenous inclusion in what schools teach, how they function, and ensuring Indigenous faculty representation. They have also been talking about how Indigenous students and their languages need to be better supported.

Given that the focus of First Nations University of Canada has been on the needs of Indigenous learners since 1976, it’s an area they already have a lot of experience.

Looking back on the history of FNUniv, Dr. Jacqueline Ottmann considers the institution she leads and how it’s grown since 1976.

“Our Indigenous elders and leaders felt that there was a need for a First Nations post-secondary institution, one that’s owned and led by Indigenous peoples… the vision began a long time ago and here we are, today, a very unique institution in the post-secondary education landscape,” Ottmann said.

“The vision began a long time ago and here we are, today, a very unique institution in the post-secondary education landscape.”

As an Indigenous institution with a long track record, there is an advantage when it comes to its area of focus.

“Because we are an Indigenous post-secondary institution, we don’t have to expend energy advocating for representation and leadership. We are already an Indigenized university and are very much aware of the devastating impacts of colonization,” Ottmann says. “We’re active in that decolonized space and have been active in that space from the inception of this university. We expend our energy in other ways and one of those ways is supporting our students.”

In addition to access to elders and ceremonies, Indigenous students are supported in how they learn and what they learn, with Indigenous ways of knowing woven into every discipline.

“One of the things that I think many people aren’t aware of is the sophistication and complexity of Indigenous intellect, something that students experience here. In many of our courses and programs, Indigenous scholars, scholarship, literature, or research is drawn upon and there is that centering of Indigenous intellect. When people learn from Indigenous scholars and researchers and elders then there is an appreciation and, for Indigenous students, a strong sense of gratitude and perhaps pride that is generated. Oftentimes, that can get lost in mainstream institutions, organizations, and in society,” Ottmann elaborates.

Without learning about the histories of Indigenous people, the silence is sometimes filled with stereotypes, something FNUniv is trying to counter.

“This university has actively been challenging those stereotypes and by centering Indigenous voices and intellect, we’re actively changing the landscape, one student at a time. That is the beauty of this university,” she explains.

With more and more institutions and organizations becoming aware of First Nations University of Canada, more hands have been outstretched in partnership to share in the wisdom of how best to support Indigenous learners and employees. Much has changed in higher education since 1976, but what hasn’t changed is the way an institution that first counted its cohort of students on just two hands is welcoming Indigenous learners with open arms.

Alumni Spotlight: Cadmus Delorme

Raised by residential school survivors in a lovely home, Delorme still grappled with what he describes as the “Indigenous modern challenges that may be inherited because of our history.” He came to the school at the suggestion of his now-wife and ended up leaving with more than a degree.

“I exited with an awakened Indigenous worldview and spirit within me that didn’t look at our past and present with anger but with excitement, hope, and optimism about where we are going to be collectively as Canadians and Indigenous people,” he recalls.

“FNUniv embedded and built a foundation, a focus on the change that is needed and a focus on Indigenous worldview principles,” Delorme says. “That place built me.”

In addition to leading his community, Chief Delorme is the first Indigenous board chair of the University of Regina, which is affiliated with FNUniv. He’s been awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal and named one of CBC Saskatchewan’s Future 40.

“Our brain and our hearts need tools and education strengthens and sharpens the tools to succeed in this world today,” Delorme says to aspiring FNUniv students. “Reconciliation is foundational in all areas in this country. Anybody who wants to attend a university for a better tomorrow needs to take a class or register at First Nations University of Canada.”

VISIT FNUNIV.CA FOR MORE INFORMATION