Hate speech on social media is a major issue across many regions of the world, including Southeast Asia.

Hate speech includes expressions to discriminate, insult, demean, or provoke violence against individuals or groups based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, nationality or others.

In Southeast Asia, TikTok has become a breeding ground for hate speech. Several studies have demonstrated that TikTok has been used to propagate racist, sexist, and homophobic language.

TikTok has policies against hate speech and disinformation, but such content persists, exacerbating the issue of hate speech in the region.

My latest research - to be published as a book chapter by Ateneo Policy Center, Ateneo University, the Philippines in January, 2024 - focusing on the 15th Malaysia general election last year, echoes this pattern.

The election in Malaysia

Malaysia has a diverse population with various ethnicities and religions, sometimes leading to tensions and conflicts.

Throughout history, Malaysian elections have frequently been marred by hate speech and propaganda.

Hate speech can pose a grave threat to national harmony and security. It is not only capable of polarising voters but can also incite violence.

With the rise of technology and the popularity of social media, the spread of hate speech and propaganda in Malaysia is becoming more widespread, making it an urgent issue that requires attention.

TikTok is popular among young Malaysians. And for the first time in Malaysia’s history, the government is allowing 18-year-olds to vote. Previously, the minimum age to vote was 21.

I utilised specific keywords encompassing the acronyms for the 15th general election in both Malay and English.

These included “PRU 15” (Pilihanraya 15, which means 15th general election in Malay) and “GE15” (15th General Election), as well as the names of significant political coalitions such as “Perikatan Nasional” and “Pakatan Harapan”.

I also included acronyms for key political parties such as “DAP” (Chinese-majority Democratic Action Party), “PAS” (the Malaysian Islamic Party), “BN” (Barisan Nasional) and “GPS” (the Sarawak Alliance Party).

In addition, I include the names of select political leaders such as “Anwar Ibrahim” (leader of the Keadilan political party), “Muhyiddin” (former minister Muhyiddin Yassin), “Lim Guan Eng” (Chairman of DAP) and “Abdul Hadi” (Abdul Hadi Awang, president of PAS).

To observe the content uploaded on TikTok approximately two weeks before and after the November 19, 2022 election, I identified 2,789 videos on the platform using specific keywords posted between November 1 and December 15, 2022.

I analysed 679 videos with over 1,000 views and found 373 containing hateful narratives and propaganda.

The results revealed Malay-language hate speech targeting non-Malays, especially the Chinese community and Chinese-language content focused on Malays and Islam in Malaysia.

For example, on November 11, 2022, a TikTok user (@125cc_madi) posted a video with over 16,000 views showing DAP supporters criticising the Muslim PAS as “stupid Muslim ulama.”

Another TikTok user, @muhdasyari6, had asserted in a video that DAP, which is predominantly Chinese, is a racist political party that seeks to eliminate the special rights of Malays. It should be noted that DAP is not a racist political party. Although the videos have been removed, controversial content related to ethnicity and religion can still be found on TikTok.

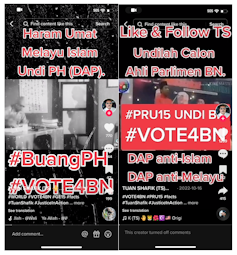

A notable example is a video posted on November 7, 2022, by a user called Tuan Shafik (@tengkushafik1).

It displays the text, Haram Umat Melayu Islam undi PH (Pakatan Harapan), implying that it’s forbidden for Malay Muslims to vote for Pakatan Harapan, as the Chinese-majority DAP in the coalition is portrayed as anti-Malay and anti-Islam.

Another example, on November 8, 2022, @Hussen_Zulkarai posted a video below accusing DAP of being sympathetic to communism, even though they are not affiliated with it. Despite being in the standard Malay language, this video is still publicly viewable on TikTok.

These videos remained on TikTok as of March 15, 2023.

This has raised questions about the effectiveness of TikTok content moderation for hate speech in non-native English-speaking countries such as Malaysia.

Emerging trending hashtags on May 13 incident

During my exploratory research, I found that hashtags #13mei and #13Mei1969 inundated TikTok amid the recent election.

These hashtags refer to the May 13 Incident, a 1969 conflict between Malay and Chinese communities in Kuala Lumpur triggered by a rally protesting the election results. This conflict led to violence, casualties, and property damage.

The #13mei videos on TikTok sparked outrage among Malaysians during the latest election, accusing political actors of exploiting the incident to incite anti-China sentiment.

On TikTok, neo-nationalists and alleged cyber troopers associated with the ruling Perikatan Nasional government posted videos suggesting a possible recurrence of the 1969 “race war” tragedy if the Chinese-majority Democratic Action Party and its coalition, Pakatan Harapan, came to power in Malaysia.

As Malaysia faced its first-ever hung parliament, with no major parties securing enough votes to form a new government, concerns arose that if Pakatan Harapan won the election, it could potentially trigger a backlash against the Chinese community.

How did TikTok respond?

Malaysian authorities contacted TikTok to address hate speech and disinformation, particularly due to the prevalence of #13Mei content.

Although TikTok’s automated system blocked thousands of videos, it was deemed insufficient as hateful content persisted on the platform even months after the election. Reports of TikTok permitting paid partnerships for political content during Malaysia’s election also raised concerns.

While TikTok has policies in place to address hate speech and disinformation and misinformation, insufficient enforcement of these policies could lead to significant real-world ramifications.

This includes heightened tensions and misunderstandings between different groups, which could potentially impact the outcome of elections.

Nuurrianti Jalli does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.