An EU/UK plan to ban their insurers from providing cover to ships transporting Russian oil is causing tensions with Washington. America contends that Europe’s dominance of global insurance will make it very difficult for Russia to export oil if this goes ahead, potentially pushing oil prices far higher than they are already.

Yet this may not happen, because Russia is making moves to overcome the problem itself. The nation’s state reinsurance company, RNRC, is reportedly stepping in to take the place of western insurance companies by insuring fleets and their cargo. Russia will also now provide third-party liability and environmental damage cover in place of protection and indemnity (P&I) clubs. If these changes are viable for the long term, it will mean that a chunk of business that used to mostly go to European and British insurance companies will now be kept in Russia.

This is only one of numerous ways that western insurance is being affected by the war in Ukraine. Insurers are already facing serious losses from sanctions passed in March prohibiting provision of various types of cover to activities related to Russia. This is having significant knock-on effects across the board for business and society. So what is happening and where does it go from here?

Insurance and geopolitics

The insurance industry dwarfs the GDP of all countries in the world except China and the US. It was estimated to be worth over US$5 trillion (£4 trillion) in premiums paid in 2021 and is set to grow 10% in 2022.

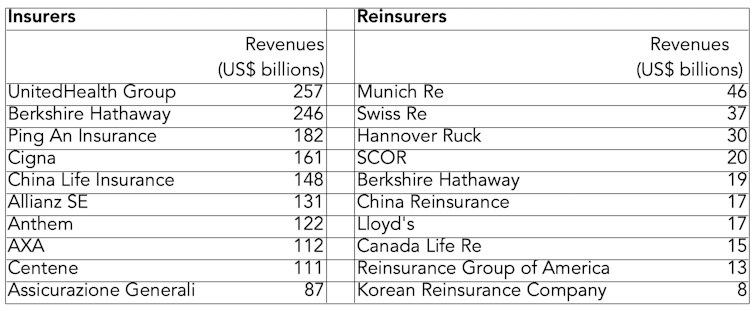

We’re all used to thinking of insurance companies as protecting people and companies against risks, but behind this lies another set of specialist companies known as reinsurers. These players insure insurance companies’ risks from say, losses arising from claims – in other words, they offer insurance taken out on insurance. In some cases, complex webs of insurance and reinsurance exist to make sure risk is adequately protected.

Largest insurers and reinsurers by revenues

Prior to the invasion of Ukraine in February, there were instances where sanctions against Russia involved the insurance industry. When the US was putting pressure on Germany to abandon its NordStream 2 pipeline project, insurance and reinsurance companies were among those who pulled out until the Biden administration softened its approach.

This time around, it’s a whole different level. Claims have been made on policies related to aviation, maritime, trade credit, cyber and political risk. This only adds up to relatively modest exposure for the industry overall, but the potential long-term effects are another matter. Since the western sanctions were imposed in March, major players such as Lloyd’s of London, Swiss Re and SCOR and brokers such as Marsh, Aon and Willis Towers Watson have stopped taking new business from Russia. With a considerable amount of insurance previously provided to Russian sectors such as aviation and space in London and New York, for example, this is a major shift.

We are now in a situation where the world’s planes no longer fly through Russia. This raises the prospect of years if not decades of claims by the owners of up to 600 seized aircraft, many of which are leased.

Counting the cost

Estimating the overall hit to the western insurance industry from the deterioration in relations with Russia is not easy. This is not least because it very much depends on how much worse the current crisis becomes, and whether a political or military solution can be reached.

In early April, a report from S&P Global predicted that the losses to specialist categories such as aviation, maritime and political risk would be in the range of US$16 billion to US$35 billion. Lloyd’s of London alone was reported in March to be facing payouts in aviation and space of between US$1 billion and US$4 billion, which is 1% of its premiums.

The industry could be affected by payouts on claims for one or even two decades, acting as a drag on insurers’ balance sheets in the meantime. Those which have not yet offloaded their Russian business also run the risk of their policies being seized by the Russian government.

Meanwhile, premiums are on the up and up as insurers seek to make up for their losses – especially in all categories besides life insurance. Global aviation insurance premiums are said to have doubled as insurers seek to protect their profit margins. Premiums on oil tankers and other important cargo in the Black Sea, such as agricultural and cereal products, have also risen significantly. This will all feed through to higher prices for consumers and businesses, even apart from all the other inflationary pressures at present.

Another affected area is cyber insurance, which protects against the risks of cyber attacks. With Russia linked with numerous cyber attacks, both in relation to Ukraine and other countries, demand for cyber insurance has risen, yet it is becoming harder to obtain and therefore prices are spiralling.

Russia is a potential winner in much of this. Assuming sanctions continue, it is likely that western insurers will increasingly be substituted by Russian insurers (and those of countries that it deems friendly). For example, RNRC is already replacing western reinsurers in relation to other cargoes besides oil. Russia may also follow the model in Iran where various new government-guaranteed reinsurance pools, companies, P&I clubs and co-insurance (multiple companies providing cover) were set up in response to sanctions.

Russian sanctions and the enforced exodus of western firms from the Russian market leave Russia with the good fortune of having internal, inherited expertise and knowledge of the insurance and reinsurance business which it did not pay for. While western insurance firms need to absorb the hit from the sanctions, it is not completely clear that their Russian counterparts will suffer in the same way.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.