Inside the Howard University pool, a couple dozen blocks from the U.S. Capitol, bouncy hip-hop blasts across six lanes of open water as hundreds of people begin to filter through the metal doors where they will witness a singular sight in college sports: an entirely Black swim team.

It’s an overcast October afternoon in Washington, D.C., and Howard is an hour from facing its cross-district rival, Georgetown, in the Bison home opener. The crowd around the Burr Gymnasium pool swells: 500, 1,000, 1,200—what likely will be the most-attended dual meet anywhere in the nation this season. Howard fans are already on their feet, chattering, smiling, pointing at dozens of warming-up swimmers flip-turning in the pool below. The DJ spins another track. Screens in the glassed-in Splash Lounge VIP section show a livestream of the meet featuring professional play-by-play and color announcers. The university dance team arrives, clad in all black.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

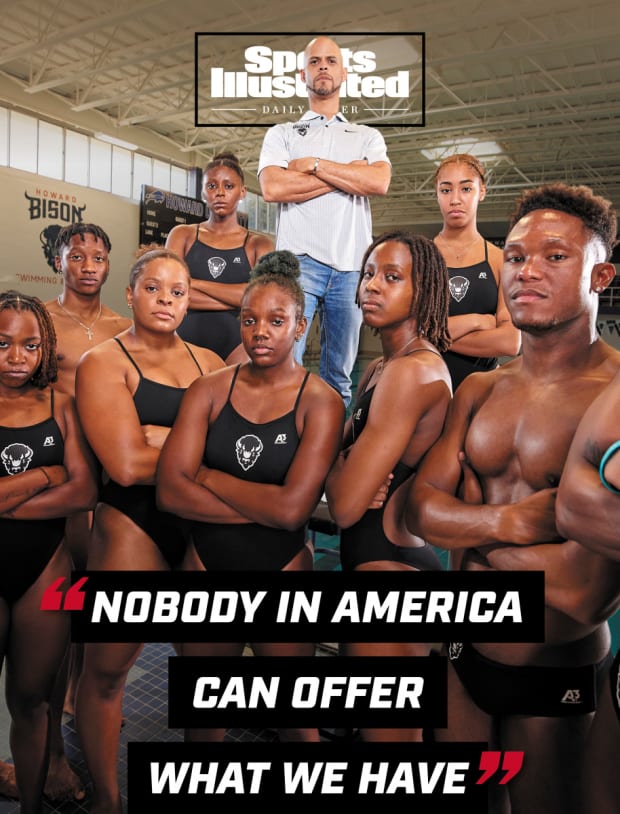

Nic Askew, the program’s 44-year-old coach, is standing alongside the pool’s wooden seats, thanking well-wishers. It’s hard for him not to feel a swell of pride with each handshake and hug and pat on the back as he moves through the crowd. Since taking over this once-moribund program eight years ago, the former Howard swimmer has created arguably the most electric collegiate swimming environment in the U.S. He’s pulled recruits from across the country, from Canada and the Caribbean, and developed a team now on the cusp of winning the Northeast Conference title, which would be its first banner in more than 30 years—the nation’s only historically Black school with a swim program now showing out in this predominantly white, country club sport.

As a mid-major, Howard may never be on the level of powerhouse NCAA swim factories like Stanford, Texas and Virginia, where success is measured in national championships. Yet the Bison’s achievement feels more significant for the beacon the program is becoming within a sport that’s traditionally failed to reach Black athletes. While college swim attendance even at the most dominant programs is often measured by the number of parents who show up, Howard these days routinely packs its stands with students, university staff and other locals. On this afternoon, the Bisonette dance team will perform poolside; the DJ will pump his music. Fans will blow horns and cheer and chant. The meet will end with 100 swimmers from each of the teams lining their respective sides of the pool and celebrating the 2022–23 Howard squad’s signature addition to the traditional handshake line: dancing to Fast Life Yungstaz’s “Swag Surfin’.”

“Nobody in America can offer what we have in our pool,” Askew says as he gets another handshake. “Where else are you going to see this?” It’s a rhetorical question, of course. There is no swim team in the U.S. like the one at Howard, a 155-year-old institution that produces Black doctors, lawyers, engineers, nurses, architects, journalists, musicians and actors, and now is seeing its potential—and sudden influence—in a place hardly anyone could have imagined.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Two weeks later, on a Saturday morning, 50 Howard swimmers are on their backs atop the gymnasium’s basketball court, stretched out with the team’s yoga instructor. Much of campus hasn’t yet croaked awake from Friday night’s parties, but the swim team is already in its first hour of work before two more in the pool.

Askew is leaning against a wall, talking to Salim King, one of his assistants. Their men and women both lost the dual to Georgetown (the men by a painfully slim two points), but the coaches were impressed by the men’s team’s dominant relays and by the performance of Howard’s best swimmer, Miles Simon, a senior from Atlanta and a U.S. Olympic Trials qualifier whom they think will reach the NCAA championships in March. There’s no disappointment this morning in the gym, only acknowledgement that the team will have to work harder, push itself a little more.

“New day,” Askew says to King.

“For sure.”

Askew is a font of positivity, a never-ending seeker of the good that’s just around the corner. It’s an attitude that dates to his time two decades ago as a record-setting swimmer and all-conference tennis player at Howard. “He always wants to know what’s next,” says King, Askew’s former teammate, who once starred as a distance freestyler. “And he’s bringing you with him.” Askew often talks about overflowing cups, about using his cup to fill others’, about the big idea he has for the Bison pool, about the team’s schedule, about winning, about the idea that America’s only all-Black college swim team could become a touchstone for underserved communities across the country.

“This is about our mission as a university and the message we want to send as an HBCU,” says Askew, who began swimming competitively as a 7-year-old in North Carolina. “This isn’t a bunch of Black people in a pool; it’s young Black men and women succeeding in a sport that, for years, has shut them out of this experience.”

That includes other HBCUs, which have cut programs over the past several decades, leaving Howard as the sole survivor. At the time Askew took over in D.C., there were just three swim programs left among historically Black schools in the U.S. By the end of Askew’s second season as coach, it was just Howard.

The coach and his staff make sure each of the school’s swimmers learns the history of swimming among Black people. “There’s a social element that’s emphasized in every part of what we do as a school, and our swim program fits that larger goal,” says Howard president Wayne A.I. Frederick. The school requires its 9,000-or-so undergraduate students to pass a basic swim test before earning their degrees. “It’s about going into the wider world, seeing inequities and closing them down,” Frederick says.

Howard’s swimmers know that European conquerors in the 15th century found thriving swimming cultures in West African coastal villages, that chattel slavery in the New World slowly robbed an entire race of its connection to water, that the Jim Crow South—and racism in the North—later prevented Black access to pools across the U.S., and that Black Americans today are 5.5 times more likely to drown than white ones.

“We were naturally in the water, and then that was taken from us,” says Miriam Lynch, a Howard volunteer assistant who swam with the women’s team from 1999 to 2004 and now is the executive director of Diversity in Aquatics, a Virginia-based organization that works to eliminate barriers to water sports in marginalized communities. “Our team is on the front line of change.”

USA Swimming estimates that less than 1.5% of the country’s 295,078 competitive swimmers are Black. Within the college ranks, at all levels, that number is just 2%. Askew does the math annually: Roughly one-third of America’s Black college swimmers are on Howard’s campus—which also means there’s a good chance that, every year, dozens of college swim coaches never speak to a single Black swimmer.

The coach stares out at the 50 bodies reaching through yoga poses on the gymnasium floor. “How many of these kids would have continued swimming in college if it weren’t for Howard?” he asks. “How many of them would have felt the same kind of support they have here?”

He thinks about the lost scholarship opportunities for young Black people who aren’t in this room, about lost chances to get into a good school and find a path to a great future. “How are you going to get a Black boy or girl interested in your sport when they don’t see a future for themselves, because no one looks like them?” the coach asks. “That’s not offering representation; that’s not expanding this sport. That’s shutting out an entire group of people.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

It wasn’t that long ago that Howard, too, seemed to be closing the door on Black swimming. Before Askew took over in 2014, the Bison men’s team had lost every dual meet for nearly 15 years straight—a streak that began during Askew’s time on the team. Swimmers sometimes were hungover at practice, if they showed up at all. One time, the school forgot to schedule transportation to pick up the team for a meet. “It was like swimming had become a joke,” says King, who still holds Howard’s record in the 1,650-yard freestyle.

Following another disastrous season, in 2013, Askew was among the most vocal swim alumni advocating for the school to kill the program. “The team didn’t embody Howard’s values,” says Askew. He had joined Howard’s tennis coaching staff as a volunteer assistant after graduating in ’01 while also coaching other programs locally (he became the tennis head coach in ’19). He worried about the embarrassment the swim program was causing the rest of the school and its other athletic programs, how the consistent failure ran counter to everything the university stood for. “If you lose every time you compete, what’s the message you’re sending?” Askew asks. “Are you helping Black swimmers, or are you making it even more difficult for them to be taken seriously?”

But Howard administrators didn’t kill the program. As Askew tells it, the former athletic director approached him one day in 2013, mentioned that he’d seen Askew’s name on Howard’s swim record board and wondered whether he wanted to take over the program. Askew said no at first. But when Howard asked again a year later—this time with a strengthened offer—he said yes. If anybody could turn around Bison swimming, Askew thought, it was him.

At the time of Askew’s hire, the Burr Gymnasium pool was affectionately known as The Dungeon. Drab, gray walls surrounded the pool deck. The stands up top were painted a fading baby blue.

The coach immediately began hitting up swimming alumni for donations. He bought some paint and hired professionals to get to work. Howard’s team was on a new track, and now Askew wanted to make the pool an attraction, one that extended beyond the cloistered swim community to the rest of D.C. The deck walls turned gleaming white. Seats were painted dark blue, except in a small section just above the starters blocks. Those were red—a little setoff for school dignitaries and other VIPs who might want to stop by. Because Askew had big plans.

He hired a DJ to hype up the crowd. He brought in the dancers. He moved his team to the side of the pool deck opposite the seats, which had less room for his swimmers but gave Howard parents and students a better view of the home team.

Progress was slow, but real: The men snapped their dual-meet loss streak during Askew’s second season, in January 2016. The following year, the men’s team won five meets and the women won four; the season after that, the women added another win to their total while the men went 8–4. A few dozen fans turned into 100. Soon, the team was regularly getting 500 people at meets against schools like Virginia Military Institute and Mount St. Mary’s of Maryland. (For reference, at a dual meet between top programs Virginia and Texas this season, the Longhorns’ 2,600-seat pool in Austin was about a third full.) “Nic has elevated swimming, in terms of our community’s consciousness,” says Frederick, the Howard president, who regularly brings his two sons to meets and signed the pair up for a summer swim league. “He’s brought fun and school pride to this program. Our university motto is “truth and service,” and part of that mission is building a community. It’s recognizing excellence in one another and celebrating that. Nic celebrates.”

Dual-meet wins have continued to roll in. The men’s team recorded a second-place finish at the Northeast Conference championships in 2022—its highest in 30 years. More than 60 school swim records so far have fallen during Askew’s tenure, including Howard’s oldest, in the women’s 1,000-yard freestyle, which a pair of freshmen each reset this past October.

All the while, Askew has led a learn-to-swim program at the university pool. He also has joined with local organizations like D.C. Parks and Recreation and the local YMCA to offer swim clinics and helped push for regular meets against Georgetown, which Askew sees as a way to broaden swimming’s reach across the city. “You hear Nic talk about our sport, and his ideas for his program, and you immediately want to jump in and help,” says Jack Leavitt, Georgetown’s coach. “He’s competitive, he’s passionate, he has a mission, he’s completely selfless. He’s exactly the person swimming needs right now.”

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

This past year has been the best of Askew’s coaching life. Last February, Howard was named the Northeast Conference’s swim coaching staff of the year. A few months later, he won the National Collegiate Scholastic Trophy, a major honor in swimming circles, in large part because it’s given by peers to the coach who has provided “the greatest contribution to swimming as a competitive sport.” Previous winners include former U.S. national team coaches, national champions and Olympic champions, the inventor of the butterfly stroke and a Presidential Medal of Freedom winner.

Askew was asked to speak at the ceremony, in Rosemont, Ill., and there he thanked his wife and his coaching staff and everyone who’d supported his program during its long, slow climb. A head coach doesn’t do it alone, he said. Askew also underscored the fact that he was the only Black head coach in the room, that his team rosters one out of every three Black college swimmers in America, that historically Black schools needed to step up and find a way to put programs back on their campuses, that the rest of the coaches in the room needed to do better at recruiting Black swimmers to their own programs.

“I stand before you as a Black man in America, in a sport that doesn’t look like me,” he told the coaches. “To me, this drives home the reason that I am at Howard, and I have been called to this sport . . . to lead the only HBCU swimming and diving program, because that shouldn’t be the case. This world and this nation are full of opportunities, and opportunities should be for everyone.”

After he collected his award, Askew headed home. He got back to work. Over the summer, he drew up practice sets, scouted possible recruits and put the last touches on the 2022–23 swim schedule, which would start with the Potomac Relays, in D.C., and end with the conference championships, which begin Feb. 21.

There were also the matters of fundraising, pool improvements and salaries—the never-ending budgetary dance for coaches in nonrevenue sports. Askew’s team costs the school roughly $100,000 each year—not including scholarships and coach salaries—a small but not inconsequential sum.

On a walk across the pool deck before practice this past fall, Askew was too busy to think much beyond the next couple of weeks. His team had a full schedule, including a big tune-up meet before winter break, where he’d get his first real gauge of how the team was responding to its training. This was the tempo-setting part of the season, getting swimmers to believe in themselves and their abilities, bumping confidence up before attempting to squeeze more out of them at the conference championships in Ohio.

During the Georgetown meet, Askew unveiled a conference-championship banner for the 1989 men’s team. It hung above the starters blocks at one end of the pool. Askew thought it offered a sense of renewal for the program, an acknowledgement that champion swimmers had once called this place home and would do so again. He also was sending a not-so-subtle message to this year’s team, a reminder of how terribly their men’s and women’s programs had performed in the decades that followed. Every time Askew’s swimmers step up to race these days, they do so under the shadow of that banner. “Coach is definitely saying something to us,” says Simon, the standout senior captain. “He’s always getting a point across.”

As the morning light filtered through a line of windows above the pool, Askew stood on the deck and admired the banner for a moment. He pointed at the white walls that surrounded the pool. The paint had been among the first signs that things were changing at Howard, a visual marker that Bison swimming was creating a future, and not just for itself. Askew traced an index finger down to the spot where the wall met the tiled floor. The bottom six inches were still the old, drab gray that had been here when he took over—the remnant of a once-failing program. The line ran the entire perimeter of the pool’s deck.

It was another one of Askew’s motivators, but this one was just for him. To anyone else, that gray line was an almost imperceptible mark. For Askew, it was a measure of how far his team had come in these eight years. It was also a warning about the precariousness of his situation, the ease with which the program could again slide into obscurity.

Askew pointed at the line. “That, right there?” he said. “We will never go back to that.”

A few minutes later, swimmers were filling the deck. The men and women spread out across the blocks as Askew pulled a pair of stopwatches around his neck. Eight swims were written in black marker on a window overlooking the pool, 50- and 100-yard sprints that encompassed all four strokes—back, breast, fly, free. Swimmers’ initials were written along the top, with room for the times they’d log this morning.

It was part of what Askew calls “positive pressure.” It’s the idea that everyone must perform every time, that the rest of the team will always know who’s striving and who’s falling short.

As the first swimmers got into their crouches on the block, the coach watched from a lifeguard stand. There was a whistle, and the swimmers were off. There were streamlines and explosive kicks and clean strokes. Calm water suddenly churned. Six flip turns and more white water. Askew leaned forward in his chair and pushed the stopwatch buttons as hands touched the wall. He wrote down the times.

“There’s no hiding here,” he said.