The words “blue economy” will soon shape the future of Canada’s oceans, from the fiords and straits of British Columbia to the rugged coastlines of the Atlantic to the vast seascapes of the Arctic. The transformation of Canada’s ocean economies will be felt throughout the country and will set an example for nations around the world.

But what is a blue economy? And what makes it different from business as usual?

The term blue economy was first championed by small-island developing countries, including Fiji, Bahamas and Palau, to bring more local benefits from ocean industries. Developing a blue economy means establishing ocean spaces and industries that are socially equitable, environmentally sustainable and economically profitable.

Canada has been a key player in these efforts, including by supporting the first global conference on a blue economy, held in Nairobi in 2018 with over 18,000 participants. Now Canada is bringing the blue economy to its own waters.

As researchers at the intersection of ocean resources, justice and policy, we believe that a Canadian blue economy can have huge benefits for all — if done well. At stake are flashpoint issues like oil and gas expansion, aquaculture and the protection of species at risk. More deeply, Canada will have to decide which people and places will benefit from new ocean investment, and who will be impacted.

Blue economies old and new

For industries like fisheries, aquaculture, tourism or shipping, achieving blue economies will mean deep transformations to address unsustainable practices, such as pollution or overfishing. New technologies, such as automated and deep-sea vessels, as well as ecological and social research will also be needed, especially for emerging sectors like wave and tidal energy or blue carbon — the management of seagrasses, mangroves, marshes and kelp ecosystems for carbon offsetting.

Read more: New mangrove forest mapping tool puts conservation in reach of coastal communities

But what sets a blue economy apart from business as usual is its focus on social equity and environmental justice. These guiding principles aim to recognize and include all individuals, prioritize the fair sharing of benefits and burdens and protect vulnerable peoples from environmental and economic impacts, natural or human-caused.

Although governments and industry are investing in new technology and research to track habitat and climate, and are aiming for environmental sustainability, these are now hardly ground-breaking commitments. Past ocean development has illustrated that ensuring benefits to frontline communities and marginalized populations, and avoiding harm to these people, will not happen on its own.

There are some good examples in Canada of how this can work well, including the federal government’s Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiatives. In the North, Atlantic and Pacific regions, these programs subsidize and support business capacity and technology for Indigenous-owned companies to invest in fisheries and aquaculture. While working within environmental guidelines, these companies can decide how to run their businesses in ways that fit their cultural as well as business goals.

Read more: Conflict over Mi'kmaw lobster fishery reveals confusion over who makes the rules

But our research shows nations around the world lack the capacity to enable equitable ocean industries and are still struggling to address corruption, human rights and basic infrastructure to build their ocean development plans. Adopting a blue economy approach would change that by first focusing on these basic enabling governance conditions.

For Canada to achieve a blue economy, it would need to develop policy strategies that address complex issues, including Indigenous fishing, ocean conservation, sustainable use, climate change and offshore oil and gas production. Because of their connectivity and role in human relationships, oceans are an important arena where these commitments play out.

‘Sustainable’ offshore oil?

The example of offshore oil and gas is a peculiar yet important aspect of Canada’s future blue economy. Under the simplest logic, the production of offshore oil and gas — non-renewable resources — cannot be part of a blue economy approach defined by equity and sustainability. This is clear given the historically uneven concentration of economic benefits from the oil industry and its chronic — and sometimes catastrophic — pollution of local ecosystems.

The inclusion of oil is especially problematic considering its contribution to climate change. Governments can propose arguments and new book-keeping to deflect accountability for downstream emissions linked to their oil and gas production, but global climate, the oceans and people will be impacted nonetheless.

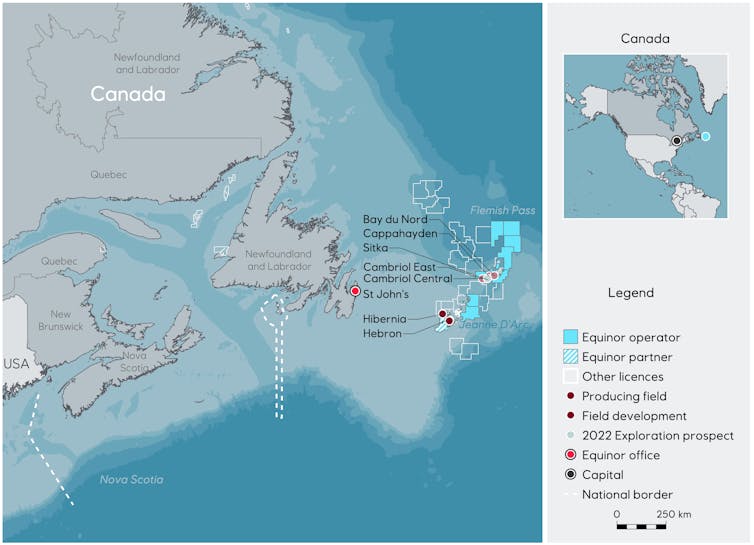

The recent approval of the Bay du Nord offshore oil project in Newfoundland and Labrador illustrates the conflict between blue economy narratives and actions. The project is supported and justified partially because of lower emissions per barrel produced relative to oil production elsewhere. Yet it ignores the emissions that consumption of the oil itself will generate.

As we argue in a recent peer-reviewd article, offshore oil and gas production could only be included within a blue economy under the strictest of guidelines: no further expansion of the oil industry could take place; subsidies to the oil sector would have to be redirected to local sustainable industries; and the blue economy plan would have to detail clear strategies, timelines and funding commitments for just transitions away from oil and gas.

A Canadian blue economy

According to the most recent federal government report Engaging on Canada’s Blue Economy Strategy: What we heard, Canadians want a new approach to ocean management and development, one that acknowledges and supports traditional relationships and industries and benefits coastal communities even while engaging with new technologies and sectors. Regulations and co-created policies and guidelines will be essential to achieve these goals in ways that are new and not just business as usual.

As Canada and nations across the world work to establish equitable, sustainable and viable blue economies, finding ocean resources will be the easy part. The challenge will be in making sure that these resources benefit frontline coastal communities now and in the future.

Listening to the diverse perspectives of Canadians is a good start that must now be followed with meaningful and ongoing support for truly transformative and equitable ocean policies.

Andrés M. Cisneros-Montemayor receives funding from Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center. He is on an advisory committee for Fisheries and Oceans Canada's Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative.

Leah M. Fusco receives funding from the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center.

Marleen Schutter receives funding from the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.