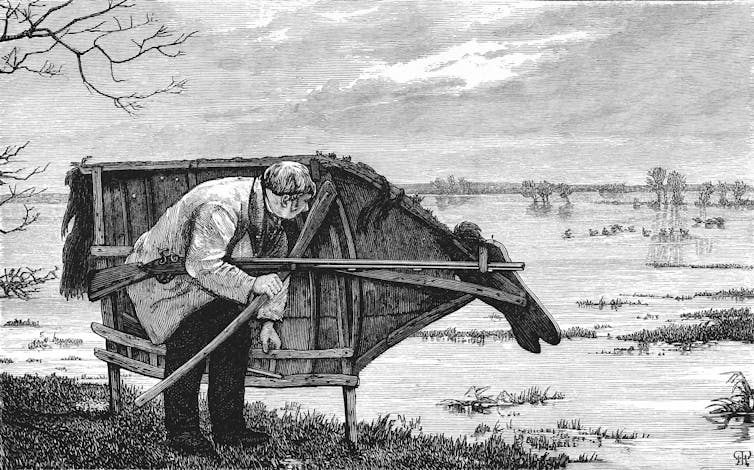

Human hunters once used stalking horses as common practice – a domesticated animal (or a wooden replica), which people guided towards their quarry while crouching behind it. People believed the stalking horse would not spook wildfowl, allowing them to approach their prey within shooting distance without detection.

My team’s new study found a Caribbean reef fish that adopts the same strategy, providing the first evidence of a predator using another animal for concealment in the wild.

Trumpetfish (Aulostomus maculatus) are predatory fish abundant throughout Caribbean coral reefs. These fish prey on small reef fish and have several different hunting strategies, including hovering upside-down to wait for passing prey.

Divers regularly report seeing trumpetfish swimming closely alongside a larger typically less-threatening fish, such as a parrotfish or surgeonfish , in a behaviour known as shadowing (also riding or aligning).

Much like the stalking horse, people assumed this behaviour allowed trumpetfish to approach closer to their prey unseen, but this hypothesis had never been tested –until now.

Model behaviour

While scuba diving on coral reefs off the Dutch Caribbean island of Curaçao, my team of researchers set up a pulley system to reel a set of 3D-printed models of trumpetfish and parrotfish along a nylon line through the water. The models were reeled one-by-one past groups of damselfish (Stegastes partitus), which are a favourite meal for trumpetfish.

Damselfish respond to potential predators by inspecting approaching fish then fleeing towards their shelter if they sense danger.

So, we filmed and analysed their responses to each model to see if they would detect a hiding trumpetfish.

When a trumpetfish model moved past alone, damselfish swam to inspect the model, then took off back to the safety of their shelter. When a model of an herbivorous parrotfish (Sparisoma viride) swam past by itself, the damselfish gave the model a once over but were far less likely to flee.

However, when we attached a trumpetfish model to the side of a parrotfish model (to replicate the shadowing behaviour of the real trumpetfish) the damselfish reacted almost the same as when it saw a parrotfish model alone: the damselfish did not detect the hidden trumpetfish.

Why disguise is important

While many animals use camouflage, even the most well disguised objects become noticeable when they’re moving. Animals can struggle to balance their need to move with their need to remain concealed and evolution has helped them develop some creative solutions. For example, the wrap-around spider, found in Australia, spins a new web every evening. At dawn it destroys the web and uses its concave belly to flatten itself around the curve of a tree branch and hide from birds during daylight hours.

And two octopus species “walk” on two tentacles to camouflage themselves as plants so they can hide from predators.

There are additional benefits of shadowing behaviour. For example, small trumpetfish may benefit from being less visible to their predators as well as from their prey. Hiding in this way may also reduce the number of aggressive encounters that trumpetfish have with territorial species.

Climate change shaping behaviour

Predators often use the physical landscape of a habitat as cover when they hunt their prey, such as hiding among rocky outcrops or vegetation. So the use of other animals may be an important alternative when habitat cover is unavailable. Indeed, in a previous study we found shadowing behaviour was more common in less complex habitats such as patchy coral reefs.

Coral reefs across the globe are facing increasingly severe challenges, including climate change, pollution and ocean acidification. They are undergoing an alarming rate of degradation, becoming patchier, less complex and less biodiverse. Given this trend, we may see an increase in shadowing in the future.

Our study highlights one of the extraordinary strategies predators use to target their prey. Human hunters may have realised that stalking horses could be used to increase their hunting success but it appears fish may have evolved shadowing long before we did.

Sam Matchette works for the University of Cambridge, UK. This project was funded by the Fisheries Society of the British Isles (FSBI) and the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour (ASAB).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.