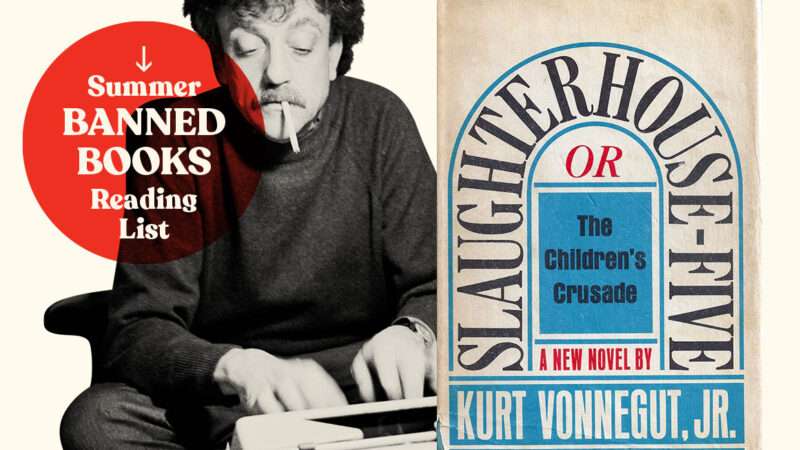

Like Billy Pilgrim, the unstuck-in-time protagonist of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade, it can sometimes feel like we're all witnessing the same censorship fights again and again.

Since it was published in 1969, Slaughterhouse-Five has been a repeated target for book burners—sometimes quite literally. In 1973, 32 copies of the book were thrown into the furnace at a high school in Drake, North Dakota, on orders from the local school board after parents complained about the book's sex and profanity. Sensibilities about those things have come a long way in the past few decades, but Vonnegut's novel is still a target. In 2011, a school board in Missouri barred the book from the curriculum and ordered it confined to a special section of the school's library.

The American Library Association says Slaughterhouse-Five was one of the most frequently challenged books of the 20th century.

It is also one of the most important books of that century for its unflinching portrayal of the brutality of war, its unconventional and deliberately meta structure, and its fatalist perspective that nonetheless eschews nihilism. Inspired by Vonnegut's experience as a prisoner of war during the Allied firebombing of Dresden, Slaughterhouse-Five explores the absurdity of mass-scale murder. It asks, but leaves mostly unanswered, the questions about free will and responsibility that recur throughout many of Vonnegut's other works.

In short, it's about a lot more than sex and profanity.

Of course, it has those things too, in ample doses, as the would-be censors point out. But just as Slaughterhouse-Five catapulted Vonnegut to fame, the attempts to ban the book boosted his standing as a critic of all forms of censorship. Vonnegut died in 2007—so it goes—but that crusade lives on through the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in the author's hometown of Indianapolis. The museum includes a library of "banned books," and the foundation behind the operation funds First Amendment advocacy efforts.

The right to express violent and crude thoughts in art is essential. But Vonnegut, cynical and ornery as he could be, always strove to make a deeper point with his vulgarity. "If you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind," he wrote to the Drake school board in 1973. "They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are."

The post How <em>Slaughterhouse-Five</em> Became a Repeated Target of Book Burners appeared first on Reason.com.