In their fight for freedom from France, what the people of Senegal keenly understood was that securing independence would simply not be enough. True victory would be achieved by a sustainable independence.

Sixty two years later, one of the most significant markers of the victory is what I call Senegal’s “de-colonised diplomacy”.

Indeed, one cannot but wonder whether the celebrated political stability of Senegal has been the result of its diplomacy or its cause.

From its effortless presidential transitions to a network of embassies that rivals that of much larger and richer nation-states, Senegal owes its success to a political governance built on a distinctive complicity between domestic and foreign policies.

This has been forged under the country’s heavily “presidential” approach to diplomacy – just like France, its former colonial authority.

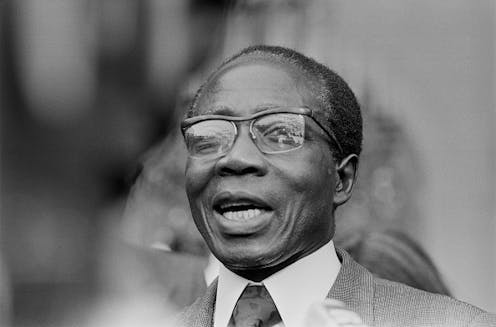

But Senegal has kept diplomacy mostly independent from the personal will of its heads of state. This remained the norm even after rewriting its constitution in 1963 and giving almost exclusive power to its first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, over international affairs.

In a paper published last year, I examined the decolonising of the country’s diplomacy through the prism of a two year window – 1961 and 1963 – and the relationship between Senghor and his American counterpart John F. Kennedy.

Though Africa has never been of primary political interest to the US, Kennedy took a highly advertised turn toward the continent. He invited more African statesmen to the White House than any President before or since. He appointed first-rate diplomats in charge of African affairs at home and abroad.

My article focused on a brief period when the leaders of Senegal and the US worked together to develop an unprecedented relationship away from the framework inherited from colonialism.

Reading recently declassified correspondence between Senghor and Kennedy, I described an unfinished policy project that, in its essence, framed the possibility of looking at the world through a new decolonised lens. Kennedy’s ‘African policy’ was neither a success nor a failure in policy-making. Rather, it was a terrain where both men fought inherited ethnocentric, colonial and Cold War ideologies to such an extent that a practice of resisting ideologies itself became the new diplomatic goal: decolonising policy.

Hopes and shortcomings

One has to look at the Senghor-Kennedy correspondence not as a political document that provides factual data but rather as a literary text that opens a fictional world. Their correspondence represents both a real agenda that the two leaders could implement. And an imagined depiction of an ideal world they wanted to see.

The correspondence was between two newly elected leaders who shared a Catholic faith largely unshared by those who elected them. They both drew on the traditional tools of foreign policy. This included cooperation, trade, economic sanctions, military force and foreign aid. But they built on these by introducing art as an instrument where colonial ideologies could be fought.

The behind-the-scenes politics of the Festival of Negro Arts is a case in point. Senghor and Kennedy did not turn to what is sometimes called ‘soft’ or ‘cultural’ diplomacy. Rather, art was used as a new practice in policy making in its own right, as a means to resist inherited ideologies.

John F. Kennedy’s short time in the White House makes it difficult to assess the desire to “decolonise diplomacy”. Nevertheless, I invite us to consider its limits and mishaps not as failures, but as symptoms of the pervasiveness of colonial ideology. And the need to persistently resist it.

In the three years between the last Senghor-Kennedy correspondence and the opening date of the First World Festival of Negro Arts held in Dakar in April 1966, the two sides collaborated little. And the new era of African relations undoubtedly shifted back to the margins of US foreign interests after Kennedy’s death on 22 November 1963.

Nevertheless, the legacy remains, perhaps, in a domain least expected in the policy area: ideology. There were of course limits. This was shown in Kennedy’s inability to free the terms of American loans as well as Senghor’s failure to sideline the influence of Britain and France.

But, in my mind, these do not signal a diplomatic failure. Rather they serve as evidence of a persistent engagement with ideological reorientation.

Continuity

In the intervening years Senegal has undergone significant transformations in its presidential regimes and approaches to international cooperation. It has, for example, constantly renegotiated long-standing political, economic, cultural and military relations with France.

Subsequent presidents may have taken a different approach to Senghor. Nevertheless, they continued a diplomacy that reconciled domestic and international interests.

For instance, in 1991, President Abdou Diouf joined the US-led international coalition against Iraq. This was not so much to seek favours with the US as to attend to a more local geopolitical issue: Saddam Hussein’s supply of military equipment to Senegal’s northern neighbour, Mauritania.

That same year, Diouf hosted the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in Dakar – a first in sub-Saharan Africa. This was reiterated by Abdoulaye Wade in 2008.

More recently, President Macky Sall sent Senegalese troops to Saudi Arabia in 2015 despite considerable linguistic and logistical hurdles. Officially, the goal was “to protect the holy sites of Islam”.

That same year, Sall also renegotiated a nearly half-billion-dollar contract with the Saudi Bin Laden Group to finish the monumental Blaise Diagne International Airport. The project had been started by Wade nearly a decade before.

Today, the airport is a major gateway to Senegal’s partners on the continent, contributing to the development of the country’s other foreign policy priority: African integration.

Indeed, embedded in its constitution is a call to

spare no effort in the fulfilment of African unity.

When it comes to France, Senegal has tried – and in my view succeeded – in remaining sovereign over a decision making process that’s evolved over time.

When Paris closed its base in 2010, some lamented that it kept 300 troops in Dakar. Yet one of the surest signs of a decolonised diplomacy is the ability to have a range of options, to not be tied to policies inherited from previous administrations or influenced by neo-colonial actors.

Senghor once said that

independence is a dream in a world where the interdependence of peoples affirms itself so manifestly.

Judging by its decolonised diplomatic journey, Senegal moved beyond the dream to realise something bigger: sustainable independence.

Yohann C. Ripert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.