For those of us who did the majority of our growing up in upper Manhattan, it’s not hyperbolic to say that New York’s Central Park was our backyard.

We spent snow days careening down Cedar Hill on our sleds. I attended a bar mitzvah reception at Loeb Boathouse, spending a good portion of it perched atop a big, flat-topped rock on the water’s edge, daring classmates to dip their toes.

Whatever the Park meant to me before the 2020 lockdown, it means more now. As a small pod of friends clung to daily outdoor meet-ups as our only in-person interactions throughout the summer, the park’s significance grew. It wasn’t just me.

“Emotionally, it was great to have a routine and reliably see people in person,” my friend Ethan tells me.

“At the end of the day, it made something fun out of a time when everything was canceled, being ejected from college, and starting work.”

HOW TO SAVE THE EARTH: On Earth Day 2022, Inverse explores some of the most ambitious, exciting, and controversial efforts to save our planet.

My experience during the Covid-19 pandemic and my rekindled relationship with public parks are not unique. I could just as easily be a person writing about Prospect Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, Chicago’s Midway Plaisance, Montreal’s Mount Royale, or the U.S. Capitol mall right now.

Collectively, these urban green spaces share an origin: They are some of the 100 public parks and grounds designed by 19th-century architect Frederick Law Olmsted. His ideas about how humans should interact with nature in cities have shaped millions of people’s existences for centuries — and amid our twin mental health and climate crises, they are once again in vogue.

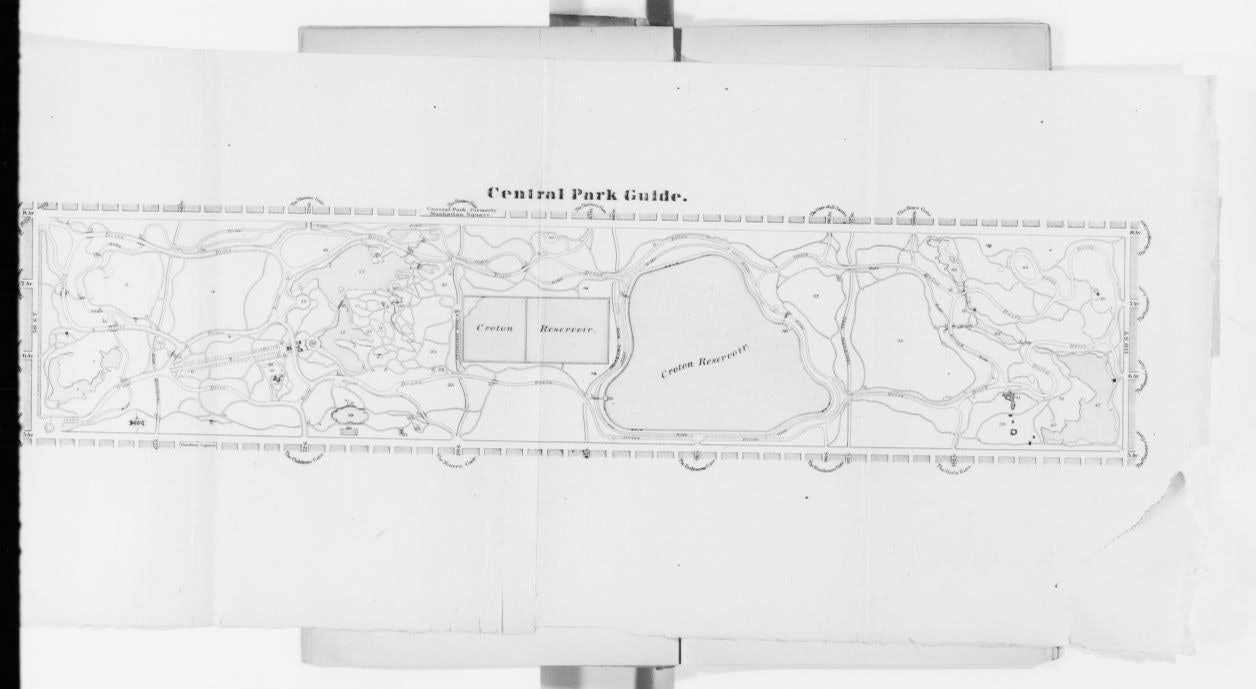

Most visitors to Central Park — or any other Olmsted park — do not realize the rolling landscape is artificial. The nature of Olmsted’s medium may have something to do with it, but it is also a misconception about how cities are designed and built as spaces for people to live.

“Landscape architects... create works of art that are constantly changing.”

“As landscape architects, we create works of art that are constantly changing,” says Thaïsa Way, a professor at the University of Washington and the director of garden and landscape studies at Dumbarton Oaks, a Harvard Research Institute.

“You can imagine Michelangelo’s ‘David:’ if every time you saw it, it was taking a different form, you would have a very different impression of that work of art.”

There’s no easy way to adequately credit Olmsted for the landscapes he engineered, short of putting a plaque on every tree, path, meadow, lake, and trash can. But his ideas altered the modern cityscape indelibly.

Two hundred years after Olmsted was born, today’s architects grapple with his legacy amid a changing planet. Architects have to adapt designs to produce climate-resilient, equitable cityscapes that keep all their residents healthy, rather than leave them struggling to breathe. Meanwhile, Olmsted’s ideas persist — both in compelling millions of city dwellers to stroll through the lush landscapes he created and in every “nature is healing” meme on TikTok.

Who was Frederick Law Olmsted?

Born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut, Frederick Law Olmsted came to landscape architecture at the age of 43 after years spent traveling and working odd jobs: He worked in a dry goods store, ran an “experimental” farm on Staten Island, and served as the General Secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission during the U.S. Civil War.

While on a six-month walking tour of Europe in 1850, he observed the grounds at Eaton Hall, an estate for the British nobility. He would later call its designer “he who, with far-reaching conception of beauty and designing power, sketches the outline, writes the colours, and directs the shadows of a picture so great that Nature shall be employed upon it for generations, before the work he has arranged for her shall realize his intentions.”

Olmsted realized that a garden or park could be a living work of art, one designed by man but then curated by nature. Coupled with his experience in farming, anthropology, public health, and design, Olmsted managed to get a job designing one of the most iconic landscapes in the world: Central Park in New York City.

His ideas for the park revolutionized how we understand the relationship between urban living and green space, and how the latter can transform the human experience.

Nature and health

It’s long been understood that proximity to nature imparts mental and physical health benefits to people. In past centuries, these apparent benefits supported the “miasma theory” of germs, which held that disease was caused by the dirty air found in dense urban centers.

To escape disease, the theory went, one needed to leave the city and get to the countryside, where the air was clean. In Elizabethan London, this was a common practice among those who could afford to leave the city whenever a plague rolled through the dank, overcrowded urban streets. In turn, breathing country air was thought to cure acute and chronic maladies.

Olmsted worked these prevailing theories of health into his designs for public parks. Reflecting on the change brought by an increase in the number of parks in London, in 1882 he writes, “the air was nearly everywhere perceptibly foul, and this to a degree often provocative, in time of epidemics, of a panicky disposition to flee the town. Where there were parks, they gave the highest assurance of safety, as well as a grateful sense of peculiarly fresh and pure air.”

“The pandemic has awakened everyone to that basic fact that we need nature, way more than what we tend to be conscious of.”

In the time of Covid-19 and the forced renegotiation of our relationship with urban centers — some estimates put the number of those who fled New York during the pandemic in the hundreds of thousands — these sentiments feel all too prescient.

Even in the absence of theories about healthy and unhealthy air, present-day studies reliably show the mental and physical benefits of the natural world. A foundational 1984 study published in the journal Science found that when people who underwent the same surgical procedure were placed in recovery rooms that looked out on either a stand of trees or a brick wall, the people in the tree-viewing rooms were discharged earlier, took fewer doses of strong painkillers, and even had a slightly lower rate of complications than did the other group.

In school settings, meanwhile, greenery is associated with higher academic achievement, increased attention, and faster recovery time from stress.

“The bottom line is that there are a lot of principles that we can apply to landscape design that are really well-researched,” says Gretchen Daily, an environmental scientist and the co-founder of the Stanford Natural Capital Project.

“The pandemic has just awakened everyone to that basic fact that we need nature, way more than what we tend to be conscious of.”

A smattering of recent research supports the benefits of engaging with nature during Covid-19 specifically. A team of researchers in China and Hong Kong studied over 100,000 Instagram posts taken in greenspaces across four Asian cities. They find that an increase of 100 new weekly cases made people 5.3 percent likelier to seek out a green space.

In New Jersey, the onset of the pandemic spurred a 63 percent increase in visitors to local parks, another study finds. A review on the same topic goes a step further, linking increased use of public outdoor spaces to positive changes in well-being, mental health, physical activity, and decreased case burdens and severity of the virus.

It seems almost too good to be true that the green spaces Olmsted designed more than a hundred years ago would prove useful all these years later. But he undoubtedly created with time in mind and estimated that his works would reach their peak fifty years from when they were constructed, Way says.

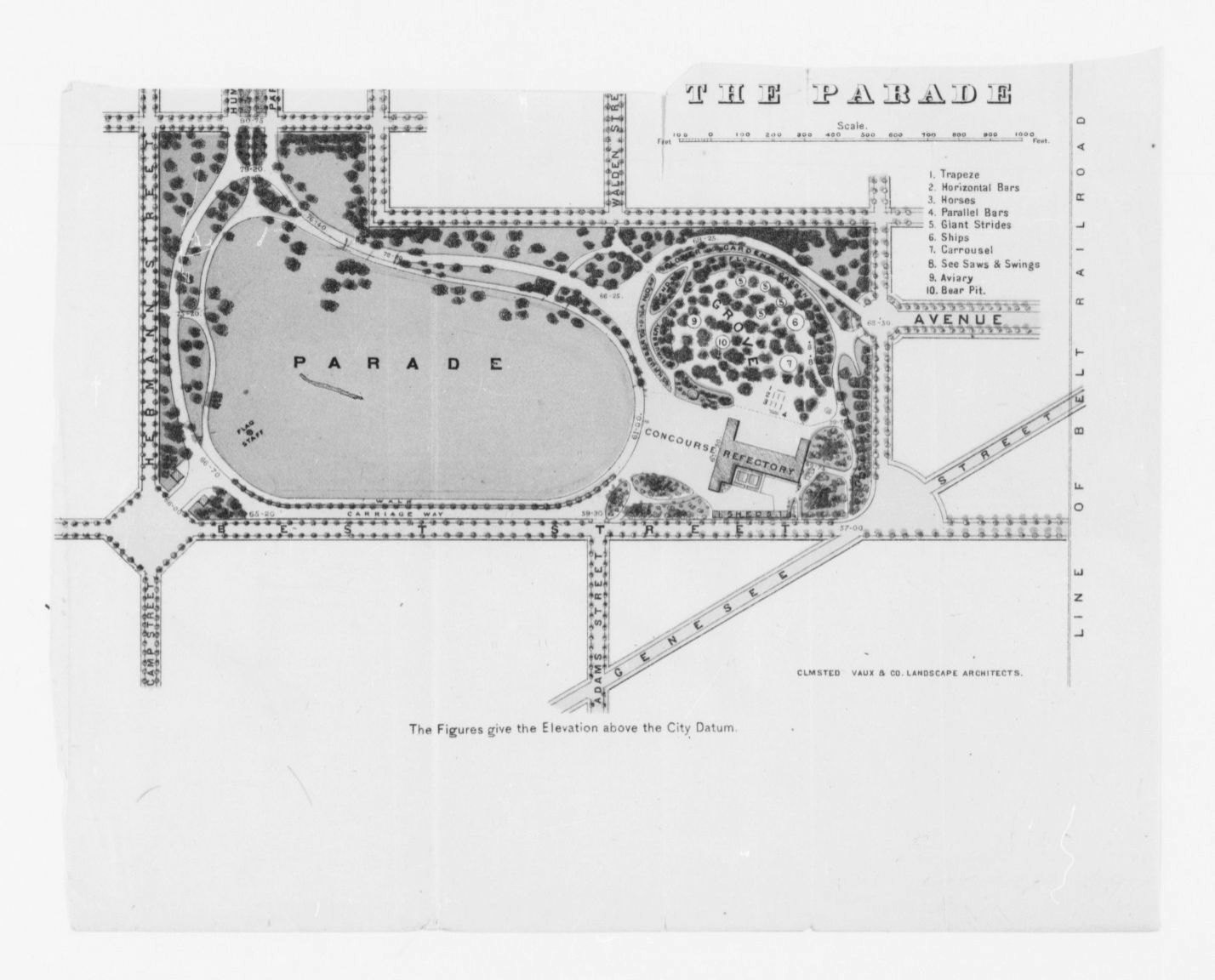

His design principles, on display in his most well-known works — facilitating an ordered flow of passersby, separating the park from its urban surroundings, and incorporating foliage that creates a sense of a balanced, natural order at play — are meant to last.

Rethinking Olmsted’s legacy

After a month inside, one of my first trips out of my apartment to Central Park in 2020 was ultimately short-lived. New York City imposed a curfew that week during the George Floyd protests, its first in 75 years. The Great Lawn was inundated with people chanting and giving speeches to the muffled drone of police helicopters overhead.

“Where do we come to celebrate? Where do we come after a crisis? Where do we come to protest? Where do we come to learn? All of those things are done in our public landscapes,” Way says.

“Central Park is a respite from the city, and a piece of the lungs of the city to allow ventilation and fresh air, but it is also very much in support of democracy.”

But it wasn’t lost on some that we were gathering not far from Seneca Village, a community of predominantly Black landowners and tenants that thrived before its residents were displaced in 1857 by New York City to build Central Park. Public greenspace’s relationship with racism and gentrification is two-pronged: Oftentimes, making room for parks displaces marginalized communities. A completed project can raise the property value of the neighborhood, leading to gentrification in and around newly “desirable” locales.

“We’re becoming an urban species — we’re expected to be 70 percent urban by 2050.”

Seneca Village is only now receiving well-warranted and overdue attention. An ongoing outdoor exhibit that debuted in 2019 comprises 16 signs that direct visitors of the Park to the sites of former houses, churches, and other points of interest.

Recent archeological efforts reveal the neighborhood was a stable middle-class community. Since November 2021, a collection of artists including Ini Archibong, Andile Dyalvane, Fabiola Jean-Louis, and John Jennings have had their work on display at The Met Fifth Avenue in “Before Yesterday We Could Fly,” an Afrofuturist rendition of “one proposition for what might have been, had Seneca Village been allowed to thrive into the present and beyond.” The period room concept lets the imaginative, vibrant, and delightfully anachronistic artifacts coexist.

Olmsted’s travels through Southern slave states reporting for The New York Times over two years (1852–54) are also largely overlooked by landscape architectural history. A fall 2020 seminar at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design re-engaged with Olmsted’s 1861 book about the experience, Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom. The writings show a side of Olmsted not on display in his later practice, including overtly racist statements amid a slow adoption of anti-slavery beliefs.

Preserving urban greenspace

Even as some follow in Olmsted’s footsteps and benefit from the public works he designed, others are looking ahead to preservation in the face of changing environments. Rapid urbanization has made Olmsted’s designs vital to cities in ways he could not have imagined, Daily says.

“He was born in 1822. Around then, only about 3 percent of humanity was urban. We’re becoming an urban species — we’re expected to be 70 percent urban by 2050,” she adds.

Yet some of his principles can inform a modern, climate-resilient landscape design. Olmsted is known for embracing polyculture in an effort to mimic the natural proportions of an area’s wildlife. He extolled the benefits of planting a less noticeable, native species, over a more beautiful imported one. He writes in 1882 that doing so, while not overly exciting, might ultimately “have touched us more, may have come home to us more, may have had a more soothing and refreshing sanitary influence.”

“You’re taking on the responsibility of designing for the public... a hugely complex client.”

Designing landscapes to last for decades may now mean incorporating climate and rainfall predictions, as well as seeking input from Native communities who may have a better understanding of traditionally home-grown species. Community food forests integrate these considerations with landscape design to harvest edible plants that would naturally grow in the regions in which they are planted.

This legacy is just one part of what Olmsted has left behind in his living works. Way emphasizes another to her students — amassing lived experience — based on Olmsted’s meandering career path and values:

“To design the landscape, you need to be an incredibly well-educated person broadly, because you’re taking on the responsibility of designing for the public, which is a hugely complex client,” she says.

My own relationship with the Park will continue to be complex: Last year, I joined the hundreds of thousands and moved out of New York. Other members of my summer 2020 pod moved, too — some downtown, others further away. My friend Ethan doesn’t get uptown to Central Park much anymore, he says.

“There’s a lot less green in Midtown,” he laments.

As we talk, he tells me that he thinks about the Park as a palimpsest, an artifact constantly reused that still retains traces of its original meaning.

“There’s all these layers of experiences and memories that have been written over,” he says.

The pandemic changed how we think of and remember the Great Lawn, just as experiences of smoking poorly rolled joints after dark have colored his friends’ perception of a gazebo near the Duck Pond.

As we spoke, it dawned on me that the analogy works well to think about the constantly changing masterpieces that are public parks and urban greenspaces. They are engineered with an eye to the future, ever erasing themselves, rebuilding, and innovating on a core that has been preserved for centuries: Humans exist in nature, not against it.

HOW TO SAVE THE EARTH: On Earth Day 2022, Inverse explores some of the most ambitious, exciting, and controversial efforts to save our planet.