**Trigger Warning: This article discusses sexual assault**

It has all the makings of a binge-worthy true-crime series but for 72-year-old French woman Gisèle Pelicot, discovering that she’d been drugged and raped by up to 80 strangers at the behest of her husband is a dark and disturbing reality.

Between 2011 and 2020, Gisèle’s husband of 50 years, Dominique Pelicot, slipped sleeping pills and anti-anxiety medication into his wife’s dinner or glass of wine. Once she was unconscious, he’d text a man he’d met on the internet and who was waiting in a nearby car park to come over. Dominique would watch and record this stranger having their way with his comatose wife’s lifeless body.

In the morning, it was like nothing happened. He returned to being the doting father and grandfather everyone thought he was. People thought they were the perfect couple. Gisele would go up the street to get a loaf of bread from the bakery and chat with a friendly neighbour about cycling. She had no idea he’d been coming over to rape her.

Dominique recruited strangers to rape his wife for more than a decade. He wouldn’t have been caught, either, if it weren’t for a security guard catching him taking upskirt photos of women at a supermarket. When the police went through his phone, they found the distressing footage of Gisèle in bed. Once they showed her, she said, it took a while for her to recognise herself, her bedding, her bedside table. She didn’t recognise any of the men, except the one at the bakery. “I was sacrificed on the altar of vice,” she said. “They regarded me like a rag doll, like a garbage bag.”

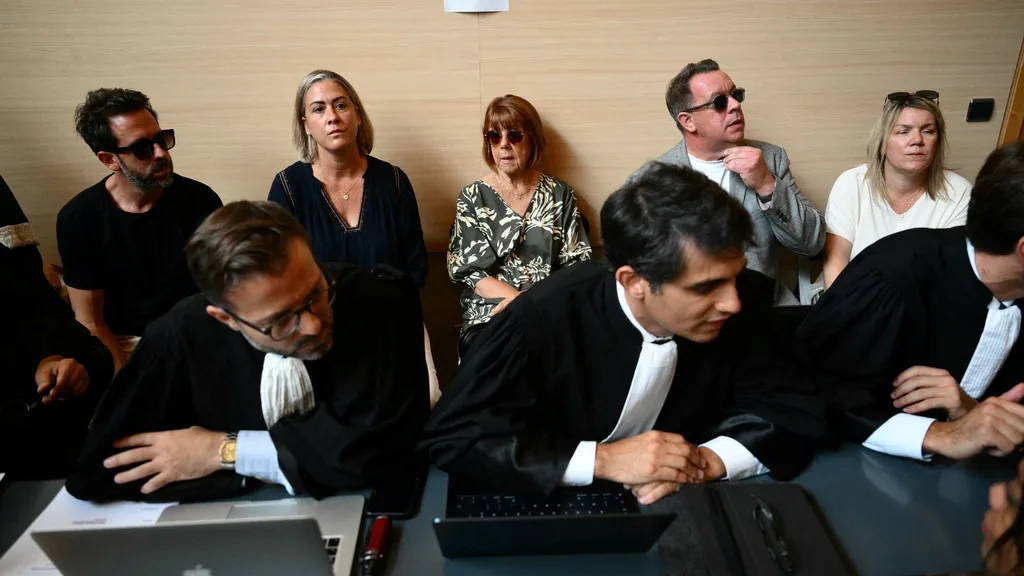

Dominique and 50 other men are currently on trial in Avignon, in the south of France and face 20 years in jail if they’re found guilty of aggravated rape. Gisèle waived her right for anonymity to raise awareness of drug-enabled sexual abuse in the home. “I speak for all women who are drugged and don’t know about it,” she said. “I do it on behalf of all women who will perhaps never know.”

But How Could They Not Know?

Gisèle said that never in her wildest nightmares did she imagine her husband would drug her. Yet there was so much she didn’t know about him. There was an earlier upskirting incident in 2010 whenDominique was caught taking photos of women in another supermarket, but was let off with a fine. Gisèle was none the wiser. She said she would have been more vigilant had she known: “I lost 10 years of my life,” she said. “Those are years I will never get back.”

It’s also safe to assume that she had no idea that police accused her husband of attacking and attempting to rape a 19-year-old real estate agent in 1999 (when he and Gisèle had been married for 18 years), and of raping and murdering another, a 23-year-old, in 1991 (when they had been married for 26). Dominique has admitted to the 1999 attack but denied any involvement in the 1991 homicide.

Gisèle’s ordeal is so horrific that it’s easy to consider it a rare and extreme case of domestic violence happening to someone else in another country. It’s tempting to believe that it could never happen here. But there’s a reason this case has captivated and horrified women the world over. It strikes at the heart of a deep, dark and often silent fear: do I really know the person I married?

“A lot of women in Australia right now would be thinking about how we choose our partners and wondering whether they are investing in their safety and happiness or whether they have another agenda,” says Danaë Owen, counselling and community engagement manager at True in Queensland. “We want our homes to be a place of safety and security, so betrayal on this scale is absolutely devastating.”

What Is Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault?

Date rape drugs are usually associated with spiked drinks at public venues: when someone tips drugs or alcohol into a person’s drink without their knowledge or consent.

Traditionally, Owen says, Rohypnol was considered the date rape drug, but “now our Emergency Departments are saying there’s a return to the party drug GHB because it’s colourless and odourless”.

GHB is the metabolised form of bute (butanediol), which, earlier this year, was reported as being increasingly linked to sexual assaults in Australia, and smuggled into the country in beauty products.

But drug-facilitated sexual assault is not always committed by a stranger and does not always involve illegal substances. For some domestic abusers, drugging their partner is another tool in their violent arsenal. “Men have been using alcohol to drug their women for years, and now there’s such easy access to household medicines, like Valium, that help render the woman unconscious,” says Owen.

Dr Siobhan O’Dean is a postdoctoral research fellow at The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney. She says it’s important to raise awareness that “drug-facilitated sexual assault is not just a ‘stranger-danger’ problem faced by people drinking in public venues. … In reality, it’s more likely to happen in contexts where the victim and offender have an established relationship or acquaintance, and often in environments where the victim should feel safe, such as their own home.”

How Common Is It?

Gisèle said she wanted the court proceedings to be made public to raise awareness of the use of drugs to commit sexual abuse in intimate partner relationships, which raises the question of how common these kinds of assaults are.

The UK’s Mirror newspaper reported in 2019 that a man named Stephen Lee had secretly drugged his wife of 17 years, Candice, so he could take and distribute photos of her naked body. In 2014, IndyStar, a daily newspaper in Indianapolis, published the story of a mother of two who accused her husband of drugging and raping her and filming it.

A 2023 study in the UK titled The Use of Chemical Control Within Coercive Controlling Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse involved the testimonies of 37 victims-survivors and nine domestic abuse practitioners. It found that more than half of the participants said their partner or ex had used (or tried to use) substances “in order to make them do something they did not want to do” in regards to sex.

Owen says that while Gisèle’s case seems so extreme, similar abuses are happening in Australia. “It’s really common, I’m so sad to say.”

She adds that some women who come to True for counselling show signs that they’ve been unknowingly drugged by a partner. “They come to us, and they know something has happened, but they’re not really quite sure. They’ve noticed bruising on their legs or tears – with younger women, it’s usually anal tears. Sometimes they’ve been feeling lethargic or thought they’ve developed a chronic illness.”

For a lot of these women, the first time they find out they’ve been a victim of sexual violence is when a doctor runs tests. “They’ll go to their GP for their symptoms and find out they have STIs,” says Owen. “We’ve had young teenagers find out they’re pregnant and have no memory of having sexual intercourse.” Other times, it’s when the police show them evidence, as in the case of Gisèle. “They’re confronted with images where they just cannot believe it, or they don’t recognise themselves in these situations,” says Owen.

O’Dean says there’s a concerning lack of knowledge about how common these incidences are in Australia. “We have very little in the way of up-to-date statistics that give us an idea of how prevalent drug-assisted sexual assault is within the context of intimate partner relationships,” she says.

In the government’s most recent Australian Personal Safety Survey, 11 per cent of women reported experiencing sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner after the age of 15. “Alarmingly, between 2017 and 2018, one-third of women hospitalised for sexual assault named their intimate partner as the perpetrator of the assault. What we don’t know is the context or content of these incidence, meaning we do not have publicly available data on the proportion of these assaults that were drug-facilitated, let alone detail on the types of drugs used,” she says. “This is a huge gap in our understanding of sexual assault within intimate partner relationships, and we need more current data to inform, develop and facilitate effective prevention and responses to such violence.”

Where Do I Get Help If I Think This Is Happening To Me?

“If you are concerned about your own safety or someone else’s, you can reach out to medical professionals who can perform tests of drugs and provide support,” says O’Dean.

Many local health districts and hospitals have specific sexual assault services available, or a GP you feel comfortable with might be a good place to start if you think this might have happened to you. You can also reach out to the police in person or via online forms like those in NSW and Queensland.”

Help Is Available:

- If you require immediate assistance, please call 000.

- If you’d like to speak to someone about intimate partner violence, call the 1800 Respect hotline on 1800 737 732 or chat online.

- If you’re under 25, you can reach Kid’s Helpline at 1800 55 1800 or chat online.

This article originally appeared on Marie Claire Australia and is republished here with permission.