The 15-minute city has, in recent months, become the focus of conspiracy theories. Politicians and pundits have described it variously as “an international socialist concept”, a “dystopian plan” and a surveillance tool “that would make Pyongyang envious”.

Quite what this longstanding urban planning idea actually results in, however, has been somewhat overlooked. A 15-minute city simply means having neighbourhoods in which residents get to do all they need to do within 15 minutes, on foot, from their home. In other words, it encourages daily active travel.

Urban planners and epidemiologists alike use the term “active travel” to refer to walking and cycling as means of transport. Research has long shown that encouraging it is beneficial for both the natural environment and the health of the people who live in it.

In a recent study, I looked at the benefits that active travel brings for children. I found that walking through their neighbourhoods – close to home – can empower young people, giving them a greater sense of control and autonomy. This can have a positive impact on their wellbeing.

How children use their neighbourhoods

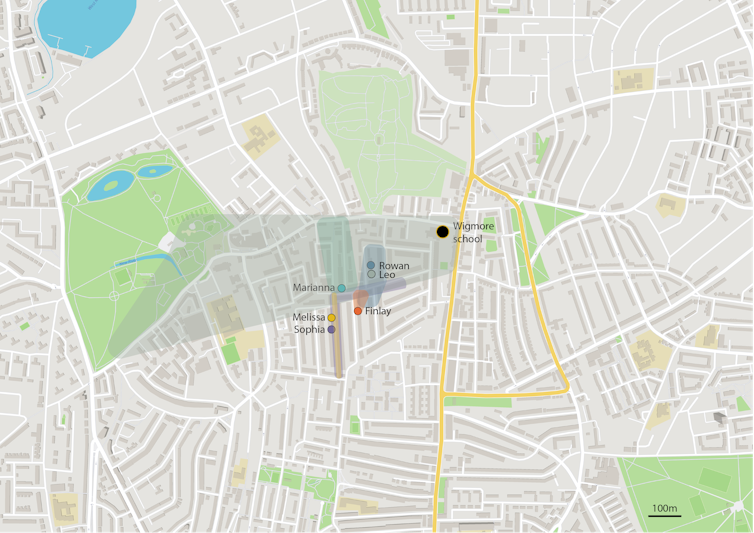

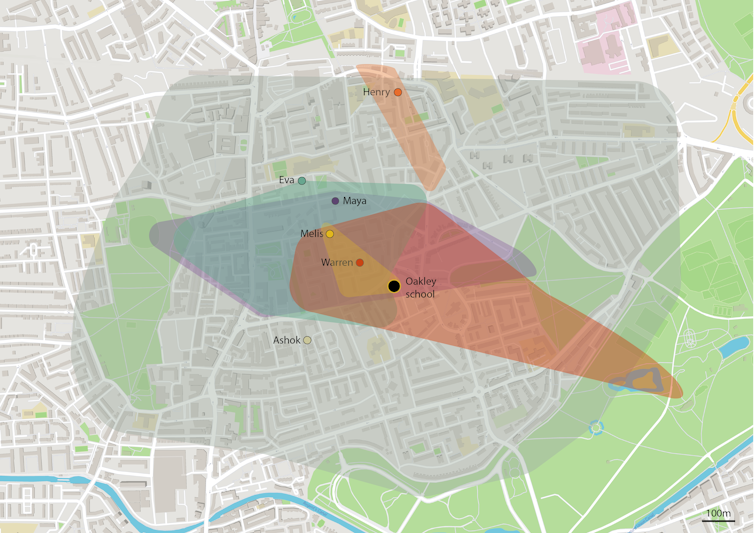

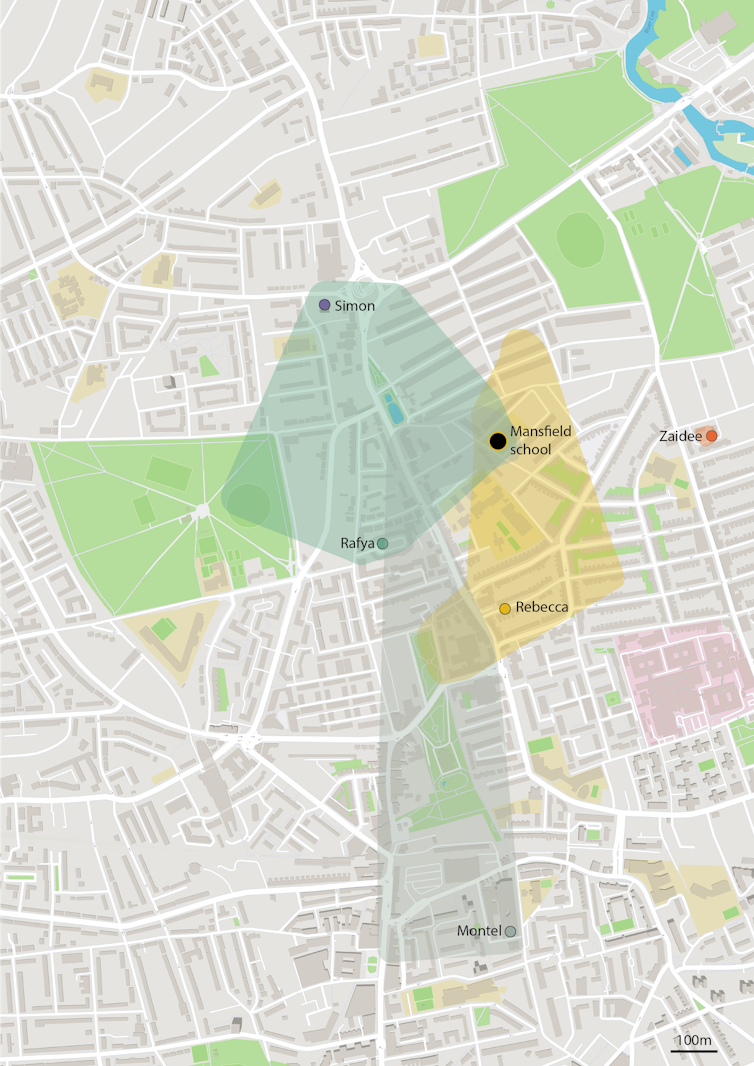

In 2019, I spent four months walking around a small part of Hackney, in east London, with 17 primary-school pupils. I wanted to find out how they use their neighbourhood – how well they know the area, where they like to go, and to what extent they’re able to move around by themselves.

The children, aged between nine and ten, were from three different schools with small catchment areas, which ensured they lived close by. They acted as my guides, taking me on walks around where they live, showing me where they liked to go and where they wanted to but couldn’t yet.

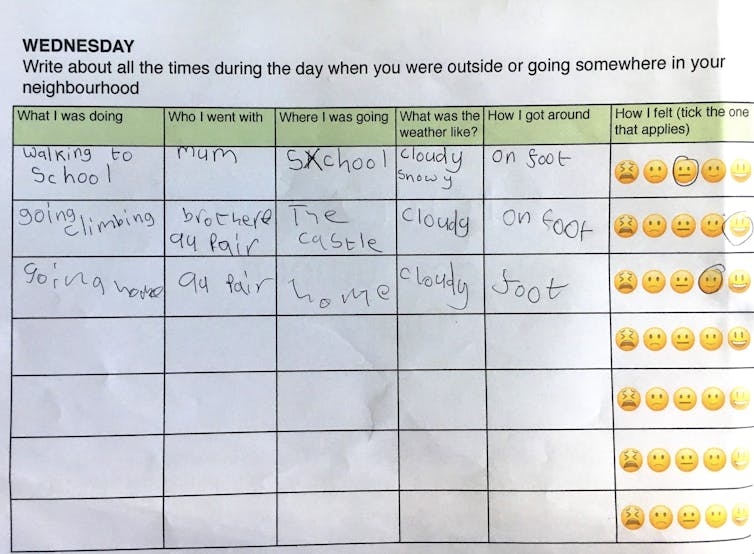

They also completed travel diaries and took photographs of their neighbourhoods. And back in the classroom, they marked everything up on a map.

Eva (all names have been changed to maintain anonymity) had been allowed out alone since she was seven. She said:

The reason [my mum] let me go at age seven is because if you don’t go outside then when you’re older you won’t be used to not staying without your mum. For example, or if your mum dies you won’t be used to walking outside so my mum let me go outside when I was younger so I got used to it.

Rowan, meanwhile, was only allowed to explore a relatively small area. Yet his descriptions of biking around the block, playing ball games with his friends and hanging out on top of the bike shed – “We just sit on them all day long” – suggested a strong sense of autonomy and empowerment, despite his always being in the vicinity of a supervising adult.

Marianna, by contrast, was allowed to travel slightly further on her own, but she had much less control and autonomy over her journeys.

I’m allowed to go up that street and go to the grocery store. And I’m allowed to go to the newsagent. But nowhere else.

Others expressed frustration at their lack of freedom. Zaidee didn’t want to play outside her home by herself. She did however want to go to her friend’s house down the road. She was upset at having to wait for her mother to be able to go with her.

Because the only reason I can’t go sometimes is because my mum doesn’t want to take me there and pick me back up.

For Sophia, her parents’ reluctance to take her to the park was similarly frustrating.

I hardly ever go to the park much as my parents are always too bored and tired to go, which makes me really frustrated and they just want me to finish my homework on time.

Why autonomy matters

Independence is the ultimate goal in terms of a child’s development into adulthood. The degree to which children move around independently, and the distances they cover, is in decline across the globe.

This is particularly the case in the UK, a country known to be more risk averse than, say, Germany or Japan. A national survey done by the UK department for transport in 2021 found that 43% of primary-school children travel to school by car and that just 4% travel to school independently.

It is generally accepted in the UK that by the time a child is in their final year of primary school (ten or 11 years old) they should be able to travel to school on their own safely. But this does not always happen. Even in secondary school, only 21% of children across the UK are travelling independently, and 37% are still driven to school.

Active travel has, of course, previously been shown to be important for children’s overall wellbeing. My findings provide a clearer understanding of why that is: it increases the amount of control that children have over their movements around their neighbourhood.

The children I spoke with did not always need to be independent or unsupervised to gain this empowerment and sense of control. In fact, for some, being physically independent came with a sense of loss. As Ashok put it to one of his friends:

You should really be happy that your mum drops you off. Because I miss that time with my mum and dad.

In what psychologists call self-determination theory, autonomy is used as a measure of wellbeing. I found that more than independence, children need to feel autonomous: to have a sense of control, initiative and ownership over their actions. This they acquire by not being part of what Dutch urban geographer Karsten Lia calls “the backseat generation” – just sitting in the back of a car.

Walking – to school, to the park and further afield – is beneficial for everyone. For parents, it makes the transition to their children going to school on their own easier. And for children it builds confidence. They gain in knowledge, navigational skills and richer experiences.

Holly Weir receives funding from Quintin Hogg Trust.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.