Language is foundational to Indigenous communities, including my own, and a vital connection to our cultures.

It is well documented how residential schools in Canada and boarding schools in the U.S. devastated Indigenous languages and severed cultural connections. While our languages are in decline, efforts to sustain them are ongoing, and I am taking part in that work.

Language revitalization efforts, both in Canada and the U.S., are opportunities for Indigenous peoples to reclaim their cultural ties. Strategies for revitalizing languages range from language documentation and mentor-apprenticeship programs to immersion language schools. I agree with linguist Nancy Hornberger, who writes that language revitalization is not about bringing a language back but bringing it forward. In other words, making sure it can be used by future generations.

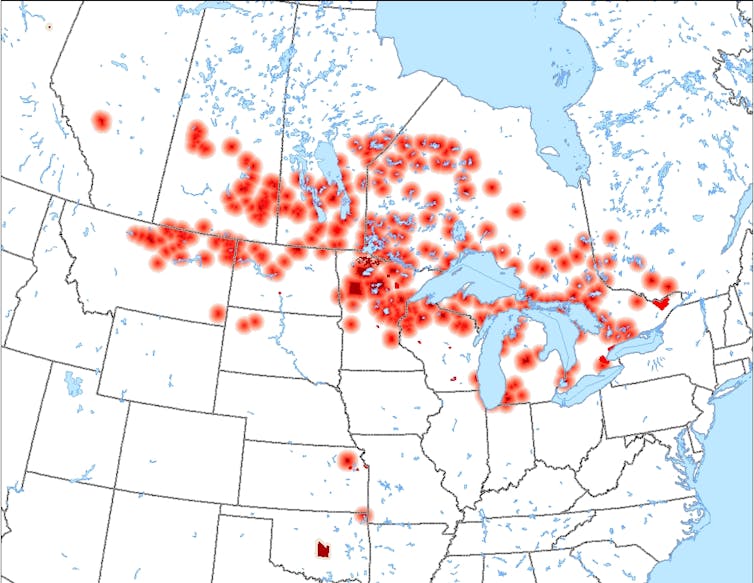

These efforts are ongoing in Indigenous communities across the world, including Anishinaabe. Anishinaabe are primarily situated around the Great Lakes and include the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi.

I am Ojibwe, a member of Michipicoten First Nation, and my work focuses on documenting the dialect of our region. After teaching at Michigan State University for three years, I accepted a position in 2022 as assistant professor in Anishinaabe Studies at Algoma University and Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

A broken link

In my family, for example, my grandmother was our last family member to speak fluent Ojibwe at home. My grandmother – and her parents before her – were relocated to residential schools, where they were punished for speaking their language. That experience and other intergenerational community traumas caused her to eventually lose much of her language fluency. After her grandmother passed away, my grandmother’s primary source of Ojibwe ended, and that was the end of the cultural transmission of language in our family.

This led to a language shift that many families and communities have faced for decades. This shift involved English becoming the primary language in the household. Most of us who want to learn Ojibwe now have to take on the challenge of learning it as a second language.

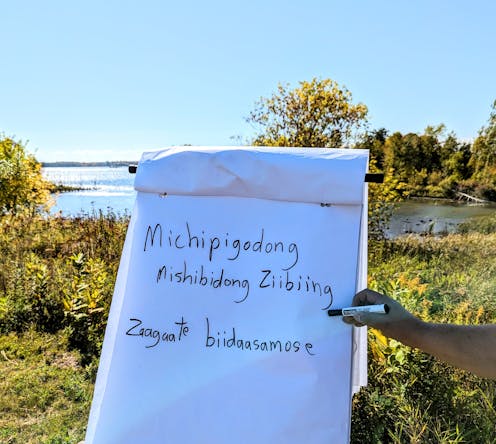

To help document more of the local variations of Ojibwe language in Michipicoten, I utilize a number of methods to gather vocabulary.

Gathering includes documenting spoken language through audio recordings and their transcriptions as well as recalling the stories behind phrases I’ve been taught. This ongoing work provides the foundation to not only preserve but to create in the language.

Rebuilding Indigenous language

Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibwe language, is spoken by Anishinaabe people from Québec to Alberta and from Michigan to Montana. Given the geographic range of the language, many dialects are spoken, and they are often broadly categorized between east and west.

They are frequently differentiated by whether short vowels are voiced or unvoiced – like “Anishinaabe” (western) and “Nishnaabe” (eastern). Michipicoten First Nation where I am working to sustain Anishinaabemowin, is most likely part of the north of Lake Superior dialect.

Although endangered, Anishinaabemowin is one of the healthier Indigenous languages in North America. Notably, it is one of three Indigenous languages in Canada, along with Cree and Inuktitut, with good odds of continuing into the next generations.

Anishinaabewakiing, or Anishinaabe territory, lies partly in Canada and partly in the U.S. – so we count Anishinaabemowin speakers in both countries together. Together, there are approximately 30,000 Anishinaabemowin speakers in Canada – which includes Michipicoten – and the U.S.

Family ties to language

Michipicoten is a small Ojibwe community with a population of 1,353 that is close to the northeastern shore of Lake Superior in Ontario, Canada. Nearly 100 people live on the reserve; most are spread out in other towns and cities.

My ongoing work with Michipicoten is to document the local dialect by working with our elders who still know the language. Because there are not many fluent speakers left in the region, it is urgent to document as much as possible.

I am keeping a record of words I remember my grandmother sharing and extending this work with other family and community members.

I recall my grandmother sharing little stories about words. One of my favorites was the time when we were sitting around the dinner table and she remembered what the old ones would call beans: “boogijimin” – the farting fruit. Everyone had a good laugh.

This summer, I spent some time with Michipicoten elders William and Myrtle Swanson, who shared stories about Ojibwe nicknames from their childhood, sayings they remember, as well as a song from their youth.

Each word and sound is a treasure to preserve.

Breathing life into words

I sometimes think about how I will never fully sound like my family who spoke before me.

Still, I am committed to gathering as much as I can, collecting whatever pieces I can, and trying to put together a puzzle I know I can’t fully complete.

As the respected Ojibwe language instructor Patricia Ningewance says, “Our language exists today because our ancestors survived great hardships. The dialect we learn is the remainder of that time. Let’s honor the ancestors by learning the language they left behind for us to speak.”

I was an elected councilor of Michipicoten First Nation for two terms, between 2017/2021.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.