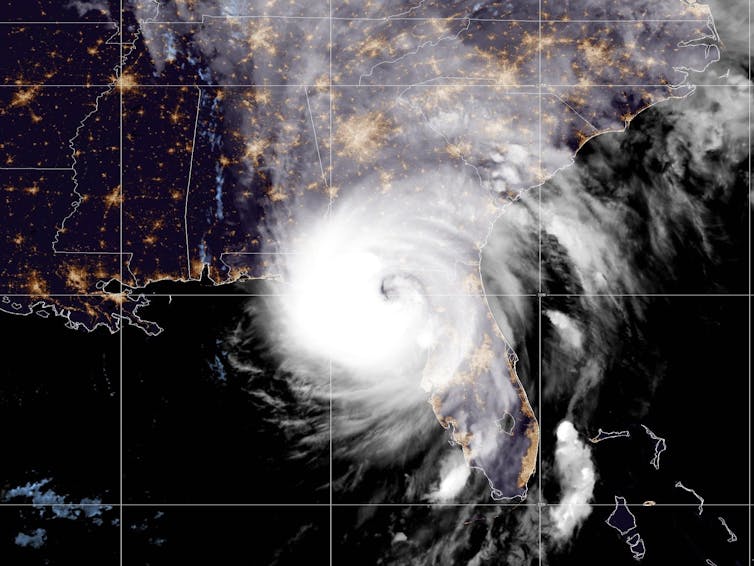

Some hurricanes are remembered for their wind damage or rainfall. Others for their coastal flooding. Hurricane Helene was a stew of all of that and more. Its near-record-breaking size, storm surge, winds and rainfall together turned Helene into an almost unimaginable disaster that stretched more than 500 miles inland from the Florida coast.

At least 230 people died across Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia as Helene flooded towns, destroyed roads and bridges and swept away homes.

In Florida, Helene’s storm surge caused damage along hundreds of miles of coast. As residents there cleaned up debris, another dangerous hurricane was headed their way. Some of the same areas hit hard by Helene on Sept. 26, 2024 – including Tampa Bay and Cedar Key – were forecast to see more flooding and an even higher storm surge in Tampa Bay from Hurricane Milton, expected to make landfall as early as Oct. 9.

The majority of Helene’s victims were far from the coast, caught off guard as the storm unleashed more than 20 inches of rain in the mountains that quickly turned streams and rivers into raging torrents.

I study hurricane history as a geographer and climatologist in one of those hard-hit states, South Carolina. Helene was by far the deadliest inland hurricane on record, exceeding Hurricane Agnes in 1972, which killed 128 people in the northeastern U.S. And it was the third deadliest in the continental U.S. since operational forecasting began in the 1960s, after Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Camille (1969).

Meteorologists routinely assess three major components of hurricanes: wind intensity, storm surge and rain. Here’s how those elements combined with Helene’s vast size and forward speed to make the storm far more destructive than its wind speed alone suggested.

Helene’s destructive winds

Helene was no doubt the strongest hurricane to hit Florida’s Big Bend area north of Tampa since 1851. It made landfall near Perry, Florida, late on Sept. 26, as a Category 4 hurricane with sustained winds of 140 mph.

The storm’s fast forward movement – it was traveling northward about 30 mph after landfall – and its large size meant Helene’s winds were still powerful when it reached Georgia and South Carolina, areas that rarely experience winds that damaging. More than 2 million homes lost power across the two states, and more than a quarter-million of them were still without power a week after the storm.

Valdosta, in southern Georgia, was hit with near-Category 2 intensity winds, around 90 to 95 mph. The city has only seen a few hurricanes over the past century, including Idalia in 2023. Augusta, on the other side of Georgia near the South Carolina border, saw sustained tropical storm wind gusts up to 69 mph.

Near-record storm surge

Helene’s size was an important factor. The hurricane was huge – about 400 miles across, similar in size to Hurricane Katrina, and among the largest to make landfall in the continental U.S.

That large size contributed to Helene’s destructive storm surge. Hurricanes push on the ocean, causing water to build up into a storm surge that can swamp the coast with water several feet above normal ocean height. Large, powerful storms push on a larger ocean area and for a longer period of time, building up a larger storm surge.

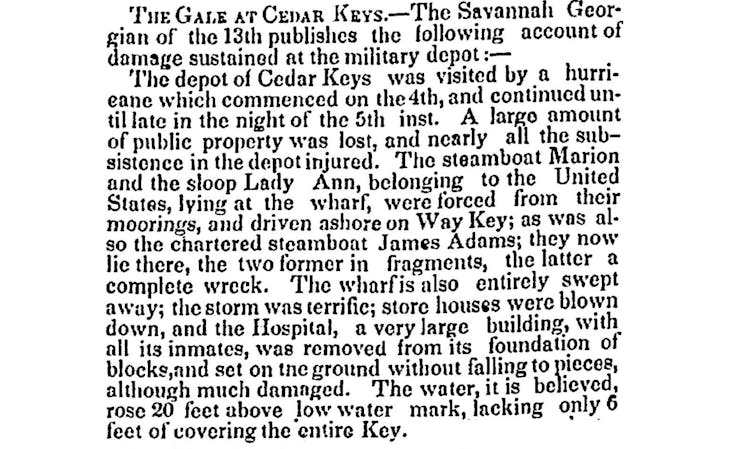

Helene’s storm surge peaked around 15 feet in the Big Bend area, according to early estimates. That would make it among the highest storm surges on record in the region dating back to the mid-1800s. Field analyses will take several weeks to verify the height.

Cedar Key, Florida, about 50 miles east of the center of Helene, had a storm surge of about 9.3 feet, which would be the highest in its 20th century record. That area reported three higher storm surges in the past: in 1896, at 12.5 feet, and in 1842 and 1848, both at about 15 feet.

Tampa Bay, almost 200 miles south of Helene’s center, saw a destructive storm surge of over 6 feet. The Tampa area has seen worse, including a 15-foot storm surge in 1848, but Helene’s damage there was still widespread. Twelve people near Tampa died in the storm.

Rain and flooding in the mountains

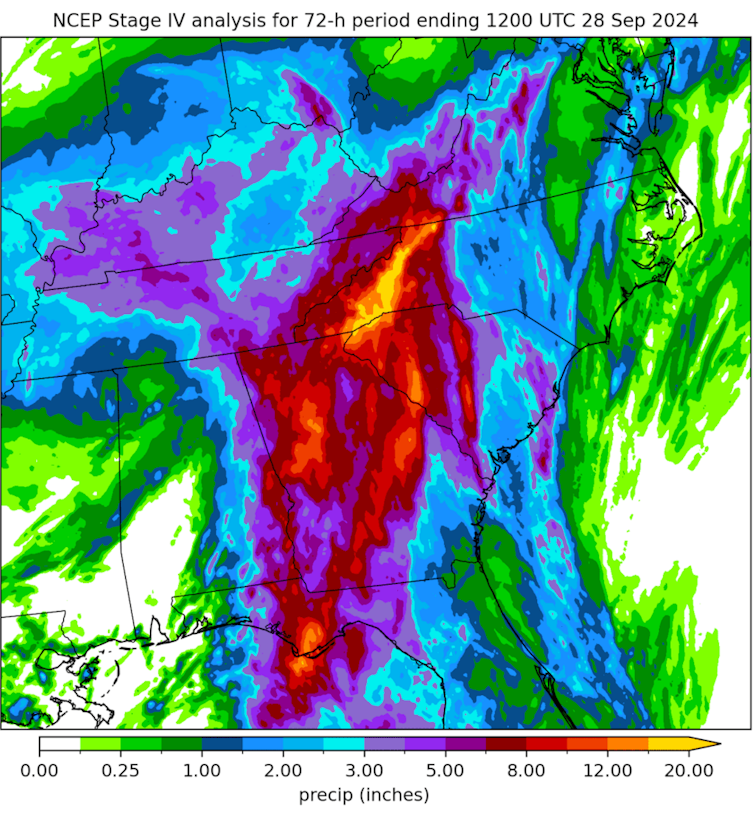

Much of Helene’s most devastating impact occurred far inland, as the storm moved up the mountains.

Normally, fast-moving storms are less of a rain hazard, but Helene was a big exception. In the southern Blue Ridge Mountains, Helene’s rain was enhanced by the terrain and what’s known as orographic uplift. When a storm is forced to rise up a mountainside, the air cools and condenses, dropping more precipitation.

In the mountains, that rainfall quickly funnels into streams and rivers. Asheville, North Carolina, a fast-growing city of about 95,000 residents, is located in a bowl in mountainous terrain. That left it and other nearby cities highly susceptible to high river runoff and extreme flooding. To make matters worse, the area was already saturated from a storm just ahead of Helene.

The French Broad River crested at Asheville at 24.67 feet, shattering the previous 1916 record of 22 feet, also caused by remnants of a hurricane.

In South Carolina, the storm was so big that its rain bands covered the entire state. The National Weather Service at Greenville-Spartanburg reported that Upstate South Carolina received 8 to 24 inches of rain.

Atlanta received 11.2 inches in a 48-hour period, setting a record.

Assessing hurricane risk in a warming world

Helene’s devastation is an important reminder that hurricanes can’t be judged by wind speed alone. The commonly used Saffir-Simpson scale, which ranks storms by Categories 1-5, is primarily based on wind intensity. Helene ranked as a Category 4 storm, but its damage was on par with some of the most destructive hurricanes in history.

As the climate warms, hurricane risk is changing. Warm ocean water fuels hurricanes, and warmer air can hold more moisture, creating stronger destructive storms. Helene’s extraordinary rainfall and the consequences may become a signature of future hurricanes.

Cary Mock works for the University of South Carolina and received funding from the National Science Foundation and NOAA in the past.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.