Hexham and its surrounds became a hub for much of the industrial and urban growth that occurred in the Lower Hunter in the first half of the twentieth century.

Major projects included the establishment of the Oak milk processing factory in 1927, the Richmond-Pelaw Colliery Railway, the Great Northern Railway line and the Hunter Water pipeline.

Earthworks associated with these projects gradually increased the concentration of freshwater in the swamp by cutting off tidal channels to the Hunter River to the north and concentrating drainage of the wetland through the Ironbark Creek channel to the east.

By the 1960s the pendulum of progress had swung to the point where the swamp was zoned 'non-urban' and 'industrial'.

In the spirit of progress, a future regional airport was among the land uses identified for the newly reclaimed land.

Longtime Hexham resident Mick Hain recalled visiting the area in the early 1960s with well-known Merewether riding school owner Wal Tracey.

"Wal used to bring his shetland ponies up and graze them during the week. He'd pick them up on Friday or Saturday and take them back to Newcastle for the weekend," he said.

"People used to come from all around to graze their animals back then."

The prevailing attitude was that grazing was the best use for the boggy wasteland on the city's fringe.

At the same time, few understood its environmental importance and its role in the food chain.

Trawlerman Geoff Hyde was among the exceptions. He recalled an area teaming with juvenile marine life that eventually made its way out to sea.

"I'll never forget the day I was working in Steelworks Channel and got 2800 tonnes of prawns in one morning," he said.

"Half of them were King Prawns and half of them were School Prawns. They all came out of Hexham Swamp. It was a magic place, it truly was."

One of the earliest recorded research projects into the area's significance involved tagging prawns in the swamp in the late 1960s.

"You wouldn't believe it, six months later they caught those same prawns off Brisbane because they had tags on them," Mr Hyde said.

But attitudes and priorities were changing.

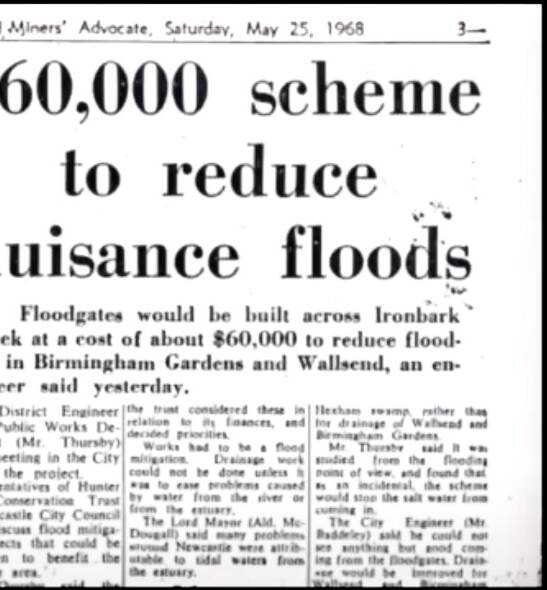

Following a series of major flooding events in the Lower Hunter during the 1950s, the idea of installing floodgates at the swamp entrance combined with a series of drainage channels was taking hold in the community.

The Department of Public Works and local political representatives were among the biggest supporters.

"A scheme has been prepared for the area which will prevent the entry of salt waters into the swamp area, drain the majority of the swamp area and reclaim areas which are now covered by mangroves," a NSW Public Works summary of the proposed engineering masterpiece stated.

"...as a result of the completed scheme, a large area of swamp will be reclaimed and could then be put to a much better type of production than is presently the case."

Local media championed the project with the Newcastle Sun declaring that the swamp was a "landmark Newcastle could well do without".

Another article justified the installation of the floodgates, described as an engineering masterpiece, and declared the swamp "needed to be cut down to size".

As a bonus, the project was promoted as a silver bullet solution to Newcastle's alleged mosquito problem.

Mr Hyde recalled being the lone voice of dissent at a series of public meetings held to discuss the plan.

"I was trying to get them to understand they didn't know what they were doing and they should forget about it. It was futile, " he said.

"There were a couple of politicians who had farms at the back of Hexham Swamp. They were the ones pushing the hardest because they wanted more property to run their cattle on."

Devastating impact

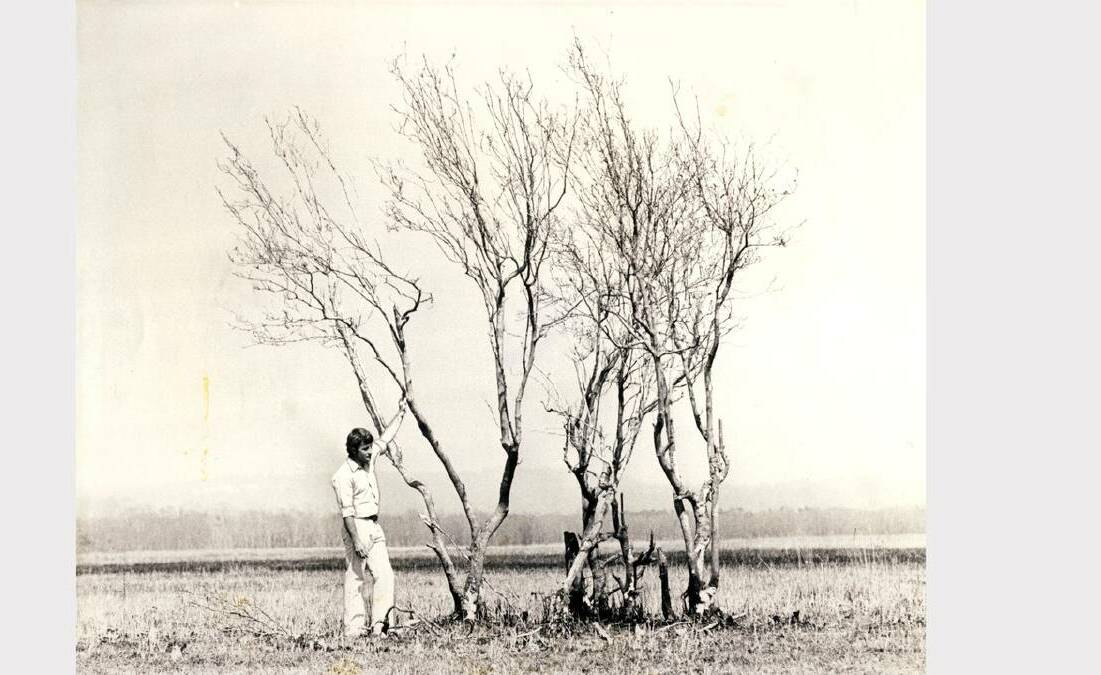

Within months of their installation, the environmental impacts of the floodgates were apparent.

The land began to dry out, the once abundant bird and marine life disappeared and, ironically, the saltwater mosquitoes were replaced with a freshwater species.

"It was instant, as soon as those gates went in that was the end of the prawns going to sea because they couldn't get in there to breed," Mr Hyde said.

In 1972 the Hunter Valley Conservation Trust expressed the view that further flood and salt mitigation works should be deferred until an environmental impact statement for the project had been completed.

It would be the first environmental impact statement undertaken in NSW under new planning legislation.

The retrospective study, published in late 1972, confirmed the area's immense ecological significance and recommended that work on the project be halted until further studies were completed.

Things remained largely unchanged until the early 1990s when the tide of environmental consciousness began to rise.

Like 30 years earlier, there were community meetings. This time the focus was to discuss whether the floodgates should be reopened for the benefit of the environment.

Not surprisingly, those who had campaigned so hard for the floodgates were having none of it.

The need to protect Wallsend from flooding was among the main concerns put forward for keeping the gates closed.

The late Jack Priestly, a significant landholder on the Maryland side of the swamp, was among those who wanted the flood gates kept in place.

"Jack was a pretty strong-willed character and he was happy to tell you his opinion about the flood mitigation scheme," Mick Hain said.

"I remember there were some meetings held at the St Joseph's old people's home, where Jack was quite vocal and quite happy to take on the establishment. He was a great advocate for keeping those floodgates working the way they were."

But it was clear times were changing. In response to increasing concern from the community and fishing industry, the Ironbark Creek Total Catchment Management Strategy was prepared in 1996.

Its key recommendation was to rehabilitate the wetland.

A survey of vegetation changes between 1966 and 2005 found the area of mangroves had reduced from 180 hectares to 11 hectares, saltmarsh had reduced from 681 hectares to 58 hectares, tidal mudflats and shallow ponds had reduced from 59 hectares to 1 hectare and the freshwater reed Phragmites australis had expanded in range from 170 hectares to over 1005 hectares.

Discussion: Do you think the Hexham floodgates were a good idea?