Last autumn, Nora Ephron’s go-to vinaigrette recipe became a major player in a celebrity scandal. In an interview with the Daily Mail (which was subsequently taken down), the former nanny of ex-couple Olivia Wilde and Jason Sudeikis conjured an indelible scene. Wilde, the nanny claimed, had been mixing up her “special salad dressing” in their kitchen – but when Sudeikis learnt that the dressing was intended for Harry Styles (who was to become, for a while, Wilde’s boyfriend), he was outraged. In a desperate bid to stop the dressing from reaching Styles, Sudeikis purportedly “lay under her car” to stop her driving away from him and their kids. “Took her salad and dressing and left them,” was what the nanny then claimed Sudeikis texted her. Both he and Wilde vehemently denied all this.

What made this dressing so “special”? Two tablespoons of Grey Poupon mustard, the same amount of good red wine vinegar, then six tablespoons of olive oil – and a soupçon of delicious literary context. Because, as became apparent when Wilde shared the ingredients on Instagram, the recipe in question was taken from the closing pages of Heartburn, Ephron’s 1983 novel. The screenwriter and director behind films like You’ve Got Mail and Sleepless in Seattle might, you imagine, have sympathised with Sudeikis’s (alleged) reaction. After all, as protagonist Rachel Samstat says at the start of the book, “you don’t just bump into vinaigrettes that good”.

Heartburn, which will turn 40 on 9 March, remains one of the definitive literary renderings of a messy break-up. Just shy of 200 pages, and alternately breezy, barbed and bittersweet in tone, it chronicles the fallout as Rachel discovers that her husband Mark, a Washington political commentator, is having an affair with “a fairly tall person with a neck as long as an arm and a nose as long as a thumb” – while Rachel is pregnant with the couple’s second child. The drama spilled onto the page from real life. Heartburn has been described as “thinly disguised” autobiography, and it’s a phrase that the author herself had “no real quarrel with” (beyond noting that those words are “applied mostly to books written by women”).

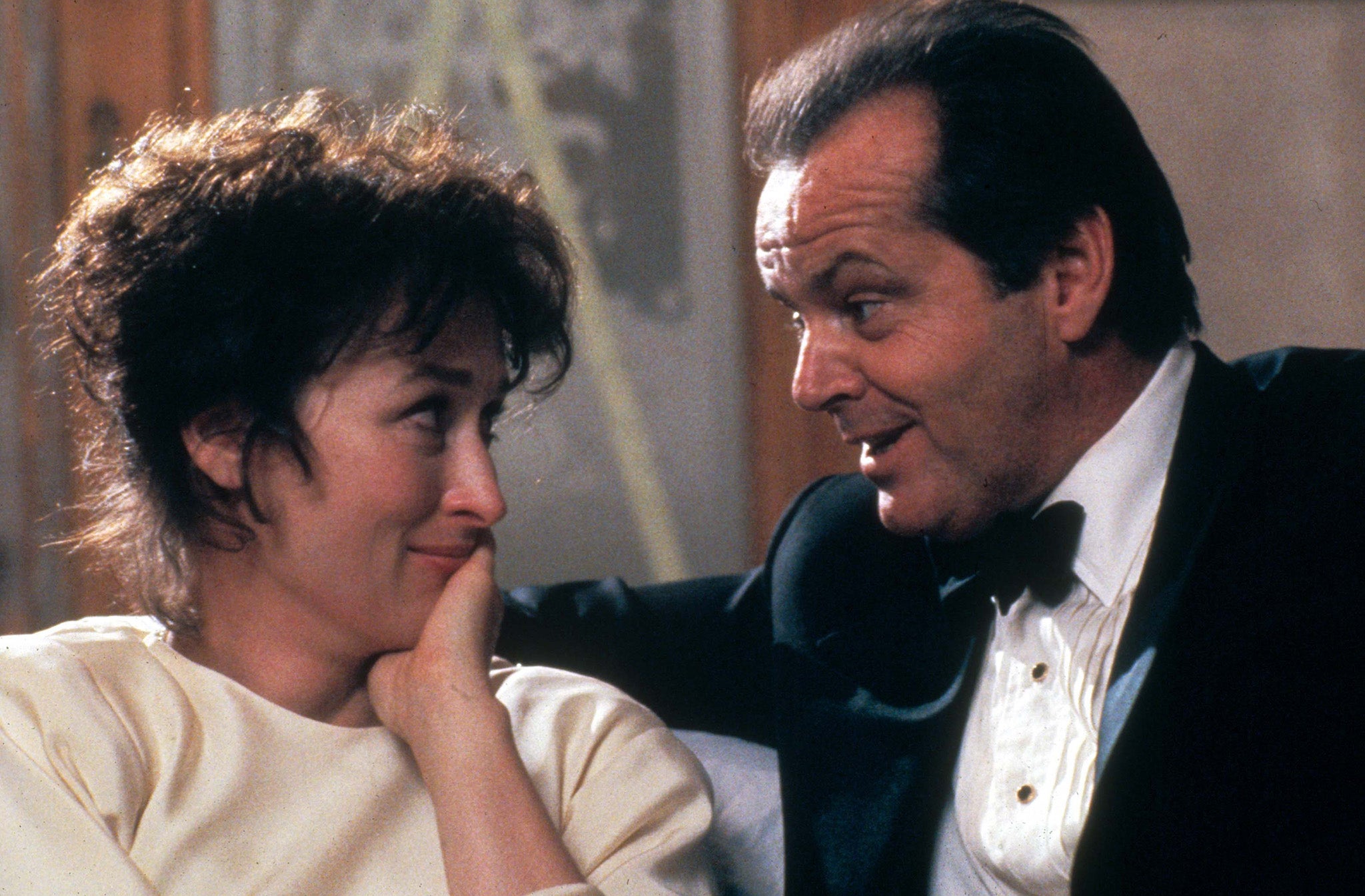

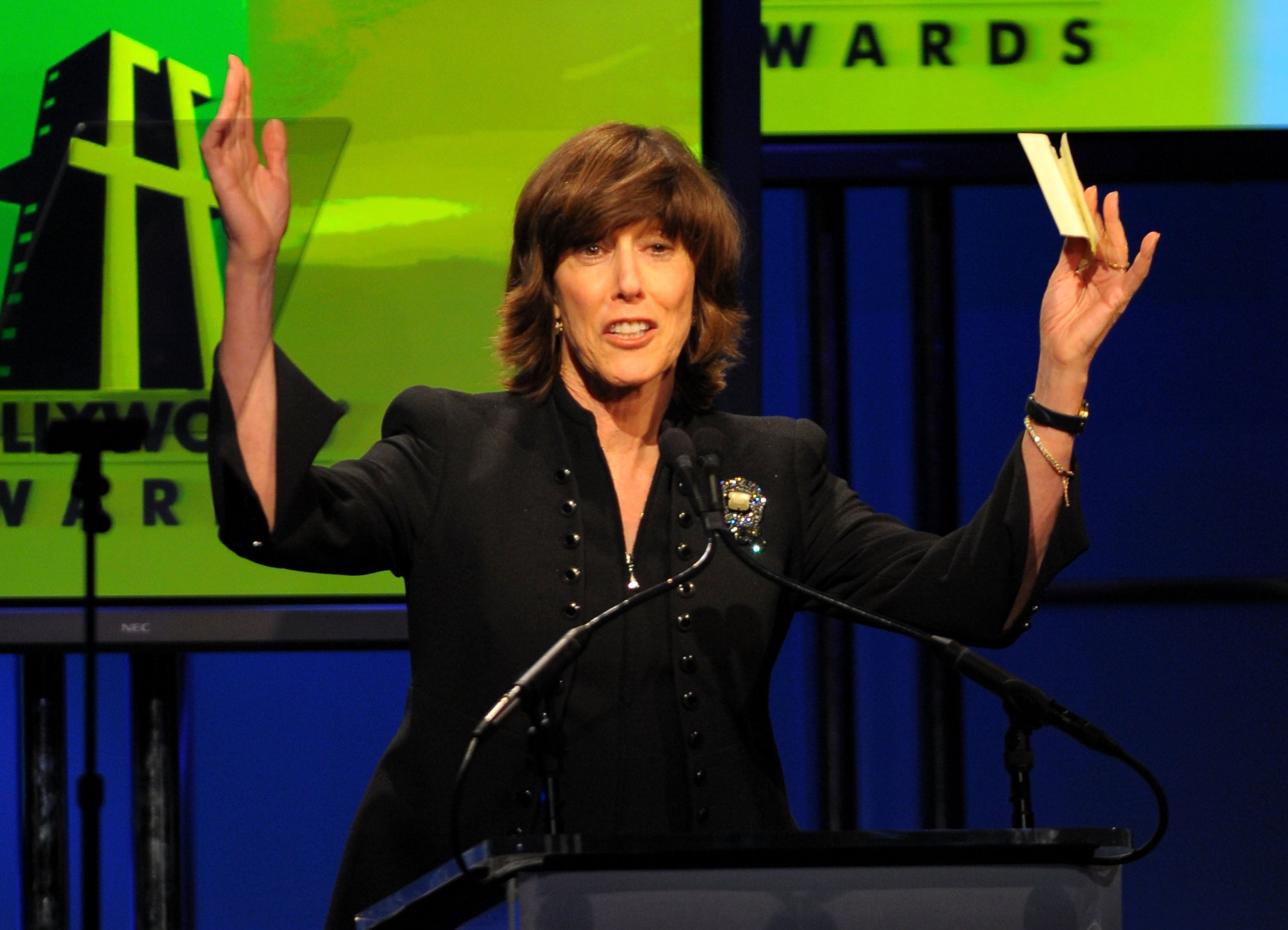

Rachel, a wisecracking food journalist, is undisputedly an Ephron surrogate (albeit “considerably more composed than I was at the time”). Mark, meanwhile, is based on Carl Bernstein, the star reporter who broke the Watergate scandal, and Ephron’s second husband. “I knew the moment my marriage ended that someday it might make a book – if I could just stop crying,” she later reflected – proof that her famous “everything is copy” mantra was always ticking away at the back of her mind. She would later turn the novel into a screenplay, resulting in the 1986 film adaptation directed by Mike Nichols, with Meryl Streep playing Rachel and Jack Nicholson as Mark (Bernstein was allowed to read the script and watch the first cut, thanks to a clause in their divorce). “I highly recommend having Meryl Streep play you,” Ephron was to declare in a 2009 tribute to Heartburn’s star.

The significance of this IRL acrimony is unlikely to have been lost on Wilde. That the Heartburn vinaigrette, one of a handful of recipes peppered into the narrative, “went viral on every social media platform” almost four decades after the novel’s publication “speaks to the legacy that Nora has”, says journalist Ilana Kaplan, who is working on a book about Ephron. The direct, almost conspiratorial way that the author writes about divorce and heartbreak is “still so applicable”, Kaplan explains, while the “familiarity” of her voice is like that of “your funniest, blunt best friend”. During the salad dressing incident, Kaplan “could just imagine Nora tweeting – reading about it and making some quippy wisecrack”.

As editorial director for Virago Modern Classics, Donna Coonan has published four editions of Heartburn so far. “It is a book that endures because it is brave and funny, because it offers hope in unlikely circumstances, and that has something to say at every age you read it,” she says. She and Kaplan are not alone in their love of Ephron’s work. In the decades since its release, Heartburn has been pressed into the hands of countless new readers by their commiserating pals, as a funny, vindicating emergency manual for heartbreak. “I’ve given Heartburn to more friends than any other book,” Coonan adds. “For break-ups, for comfort, and just because Nora has a voice I have to share.”

Many of us are introduced to Heartburn during times of heightened emotion, when we’re feeling fragile, seeking escapism, in need of a reminder that life always goes on, as it does for Rachel (after she has thrown a key lime pie at her husband’s face, in a real “mic drop” moment, as Kaplan puts it). Perhaps that’s why Ephron’s book seems to have such a lasting impact. Coonan says she “first encountered it [after] I’d just been cheated on by my serious boyfriend – fittingly enough, a chef. Now I think the heartbreak was a fair trade for being able to make perfect spaghetti aglio olio e pepperoncino.” A sentiment worthy of Rachel (and her creator), surely.

Ephron and her book weren’t always so beloved. Heartburn may have shot up the bestseller charts, buoyed by the glimpse it offered into the break-up of “the Brad and Jen of the early Eighties”, as writer Ariel Levy would brand them in a New Yorker profile, but reviews were mixed. One Vanity Fair columnist, writing pseudonymously, described it as an act of “indecent exploitation” tantamount to “child abuse”. It was cruel, the anonymous author reasoned, to create such a permanent and public record of marital discord, which her children might one day read. Many of her films, meanwhile, were commercially successful but critically middling, often derided as fluffy, guilty pleasures; some were outright flops.

But in the decade or so since her death in 2012 at the age of 71, her work has been reappraised, reinforced by a raft of big-name recommendations. Nigella Lawson describes it as “the perfect bittersweet, sobbingly funny, all-too-true confessional novel”. Amy Poehler says she kept a copy of it beside her when working on her own memoir, “as a reminder of how to be funny and truthful” – but “all I ended up doing was ignoring my writing and reading Heartburn”. Her fellow comics Tina Fey and Mindy Kaling have also hailed Ephron’s influence, while Stanley Tucci has written the introduction for Heartburn’s new 40th anniversary edition, published by Virago on Thursday (the audiobook is read by Ephron’s pal Streep).

A younger generation of millennial and Gen-Z fans, raised on the nostalgic near-past of When Harry Met Sally and You’ve Got Mail, welcomed her with open arms, claiming her as their own. They care less about the biographical resonances, more about Ephron’s “truth-telling”, valuing “her emotional honesty, rather than the real-life parallels”, as Coonan puts it. Heartburn’s “truth-telling” is couched in a voice that is both intimate and piercingly sharp, welcoming you in as it observes others at an ironic distance. It is boldly decisive, almost aphoristic at points, qualities that flavoured all her writing, from screenplays to personal essays. “What Nora lacked in resumé, she more than compensated for in decisiveness,” her friend Richard Cohen wrote. “It could be as good as wisdom.” Reading Ephron sometimes feels like being drawn into a fantasy of confidence, in all senses – of closeness, yes, but also of having the stridency to say whatever you want. Hers is a conviction that’s almost certainly rooted in a privileged life as the daughter of two successful Hollywood screenwriters.

Lines such as the much-cited “never marry a man you wouldn’t want to be divorced from” (which appears in essay collection I Feel Bad About My Neck) have a clever symmetry to them, one that feels deceptively simple. It is easy to fall for her style, but much harder to pull it off yourself. The label of “the new Nora Ephron” is a useful one for publishers, but few of them balance the content (relatable heartbreak, self-deprecation, a fondness for potatoes of all forms) with the form. Kaplan reckons “there are elements of her humour, her candour and the frank way she talks about female friendships and marriage in other writers”, but she “just can’t” pinpoint someone who has crafted a similar voice. Coonan, meanwhile, says she “see[s] glimmers of [Ephron] in writing that acknowledges the bittersweetness of life, that doesn’t shy away from the tragedy, but makes you laugh anyway… I nodded in acknowledgement to Nora when I watched Fleabag by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and read Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason”.

Ephron’s writing does have some uncomfortably sharp edges. There are certain passages in Heartburn that will land with a thud in 2023 – like the dated, casually racist references to black and Latinx characters. And there are sometimes touches of cruelty in her descriptions, which, according to a New York magazine piece published around Heartburn’s release, at least, could crop up in her real-life conversations too. “When her name comes up” in literary circles, journalist Jesse Kornbluth wrote, “you are much more likely to hear it from someone who has been the target of one of her barbs”.

The author herself was spiky, imperfect, like many of her creations – and yet sometimes we risk sanctifying her in a way that robs her of these edges. Since her death, “a writer of tart, acidic observation has been turned into an influencer, revered for her aesthetic, and her for arsenal of lifestyle tips”, Rachel Syme observed in The New Yorker last year. And as writer Ella Risbridger noted in an episode of the podcast Sentimental Garbage, she has become almost aspirational, “a signifier of who people want to be… Liking Nora Ephron is a kind of cultural marker for a certain kind of woman”.

That woman, to generalise wildly, might be smart, city-dwelling, ready with a one-liner, fond of autumn and nice knitwear (you can even order “written by Nora Ephron” tote bags and t-shirts to really buy into the brand). When Olivia Wilde shared her vinaigrette recipe, then, she wasn’t just providing a tabloid clapback, but positioning herself as an Ephron woman. In a way, though, this commodification makes perfect sense. Writing in The Paris Review, Matt Weinstock describes Ephron’s “impulse to refashion her peculiar impulses into a glossy commercial product” as “the defining tic of [her] career”.

Ephron metabolised emotional messiness and transformed it into something shiny, quippy and sellable – so is it any surprise that we’re desperate to transform this spirit again, into something we can actually buy? Isn’t Heartburn the epitome of transfiguring emotions into appealing (and lucrative) products? “I turned it into a rollicking story. I wrote a novel. I bought a house with the money from the novel,” Ephron would later say.

The idea that we can turn a painful experience into something vindicating and cathartic is certainly an appealing one. Heartburn’s final, and most intoxicating, fantasy is not necessarily revenge, but control. It’s about being able to tell a story on your own terms and becoming master of the situation. “Because if I tell the story, I control the version,” Ephron writes at the end of her novel. “Because if I tell the story, I can make you laugh, and I would rather have you laugh at me than feel sorry for me. Because if I tell the story, it doesn’t hurt as much. Because if I tell the story, I can get on with it.” We might not all be able to write (or sell) like Ephron but, she seems to say, we can still take control of our own stories – and have the last word. Won’t that always be a reassuring mantra?

A 40th anniversary edition of ‘Heartburn’, with a new introduction by Stanley Tucci, is published on 9 March by Virago