The going rate for cameras hasn’t really shifted much since the digital revolution solidified the camera industry’s casual, enthusiast, and professional lines in the sand — which on the surface seems like a great thing for us consumers. The same chunk of change today gets better autofocus and high ISO performance, higher resolution and continuous shooting speeds, and improvements in video compared to what it did in generations past.

The thing is, though, I reckon we went past the point most upgrades mattered to most people quite some time ago. Whether it’s the budget end of the market, where improvements have largely stagnated over the last decade as cameras are more or less rebadged, or the high end where resolutions go beyond the reasonable limits for print size and continuous shooting speeds fill cards with near identical shots, there’s a limit to the benefits of the ever-forward march of technology.

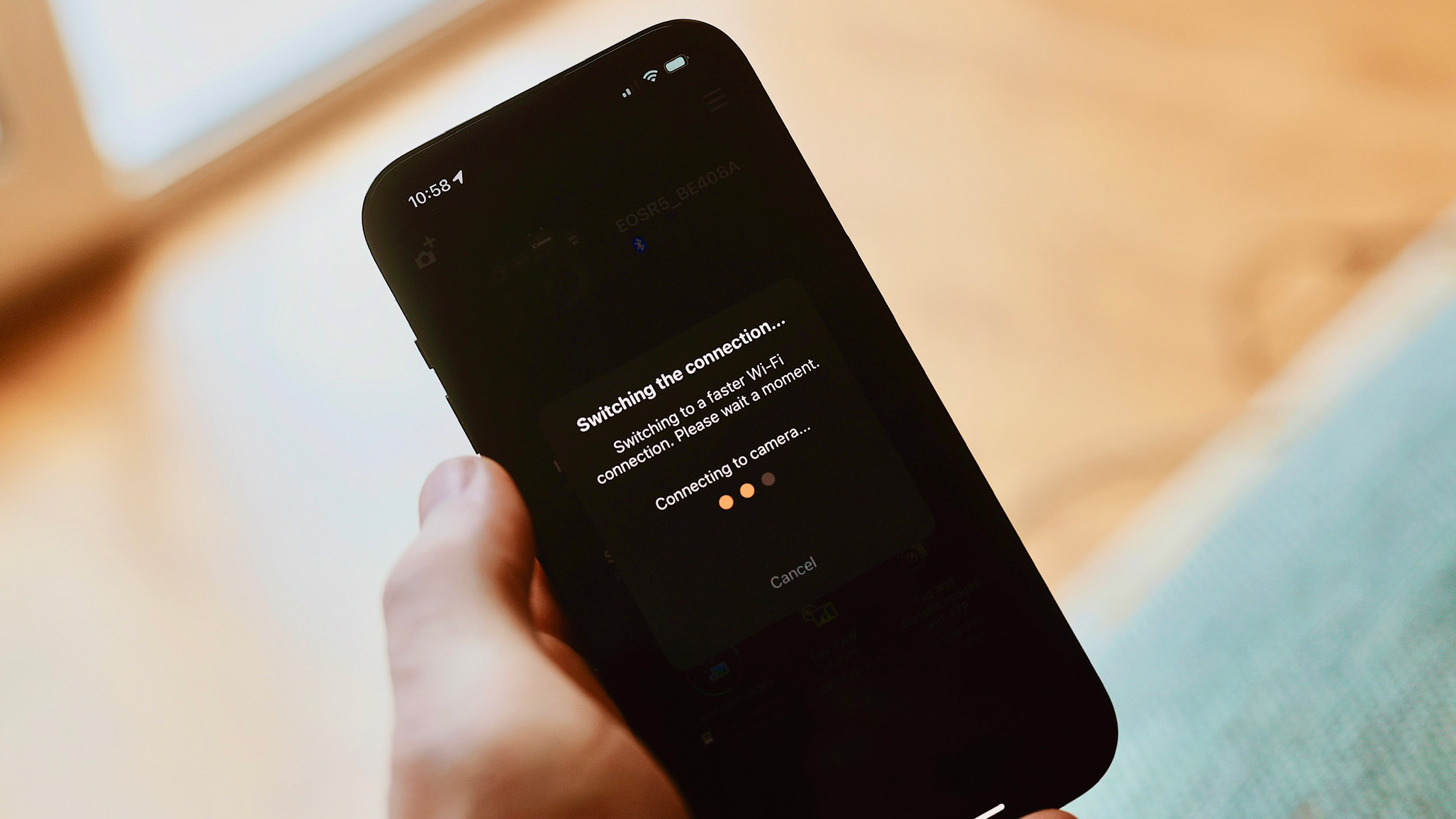

I don’t know about you, but I’m annoyed by my camera and phones’ refusal to play nicely with each other around a hundred times compared to every solitary time I wish I could fetishise an A2 print with a loupe, or missed a shot halfway between two tenth’s of a second with a 10fps camera and lamented not getting the 20fps model, or indeed even felt I absolutely had to shoot action at f/8 at dusk and damn this camera starting to get noisy at ISO6400 and beyond.

My iPhone can immediately recognise my nearby Mac and Airdrop hundreds of megabytes to it, over Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, in mere seconds. I’d be much more likely to carry a pocket-size 1-inch sensor camera around with me if it were as simple but, instead, I’m yet to use a camera from any manufacturer that has anything but a nail-biting, agonising connectivity process.

Ever since the tide of TikTok told thousands that FujiFilm's film simulation modes were the ultimate in desirability, getting your hands on a Fujifilm camera has turned into a games console-like waiting list affair. Judging by this, perhaps what many people are really looking for from a purchase is something that makes ‘done’ simpler.

All the stylish and artful things that apps do – facilitated by the extra data available to them in the phone camera’s imaging pipeline – could surely be done so much better if that raw data was coming from a dedicated camera’s larger sensor and higher resolution lens. Give me a pocketable 1-inch sensor camera that embellishes bokeh more believably than a phone ever could and tone maps the full dynamic range of the sensor into an image more vibrant and alive than possible when slapping a filter on a JPG. Hey, give me a full-frame camera that does the same to push the look into large format territory; have you seen what the latest Lightroom depth mapping can do without even having access to the pixel-level focus data that modern sensors obtain?!

Use IBIS and focus pixel data creatively (Canon’s Dual Pixel RAW is an example of toes being gingerly dipped in these waters) to create more convincing stereoscopic and 3D extrusion shots. Spit out gifs of bursts. Give us multi-shot stitched photobomber removal. Look in the beginner end of the market and you’ll find all sorts of auto and outdated ‘creative’ modes, but move into enthusiast level and it seems that manufacturers think more pixels, more shots per second, more numbers are the drivers.

Of course, if this sounds like fluff to you and all you want is ‘the shot’ more power to you. There are days I feel like that too, and a camera from generations back suits just about any aspiration I have regardless of whether I’m in the sports and wildlife or portrait and landscape lane with the opportunity cost of the extra few megapixels or frames per second much lower value than the lens I could get with the money saved.