The script for celebrated Brazilian architect Marcio Kogan’s life was written from an early age. While there have been plenty of plot twists along the way, it was clear from early on that the two main protagonists would be architecture and film. Whether it’s synchronicity, or divine direction from on high, there are a handful of formative scenes that have shaped his journey throughout the years. Sometimes tragic, sometimes comedic, always fateful.

Into the world of Marcio Kogan

The inception moment happened in 1958 when a young boy enters stage right and gets a little too close to an unsecured edge of one of the buildings going up in his hometown, São Paulo. As our young hero walks towards the urban landscape lurching upwards, as if reaching for modernity, the boy’s father grabs his hand to protect him from falling into the building works below. ‘It was at that moment that I realised I’d be an architect,’ says Kogan, recalling fondly his father’s powerful presence on his younger self.

Marcio Kogan: into the mind of the architect

In his formative years, the young boy would watch in awe as his father, Aron Kogan, the talented engineer and architect, built and designed everything in the family modernist architecture home in São Paulo. As well as ‘the house of the future’ he shared with Marcio’s mother, Kogan Senior went on to draw up plans for Brazil’s tallest building, the 51-storey office, Mirante do Vale, in 1960, before he was killed tragically a year later. The needless loss would send his nine-year-old son’s life into darkness, a broody monochrome, real-life remake of JD Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. ‘Holden Caulfield was my name,’ he recalls of the angst he felt in his early teenage years. ‘Constantly wandering through the streets of São Paulo, always trying to escape school, where I was probably the worst student. In the 1960s, I lived in a black-and-white world, in deep and anguishing silence.’

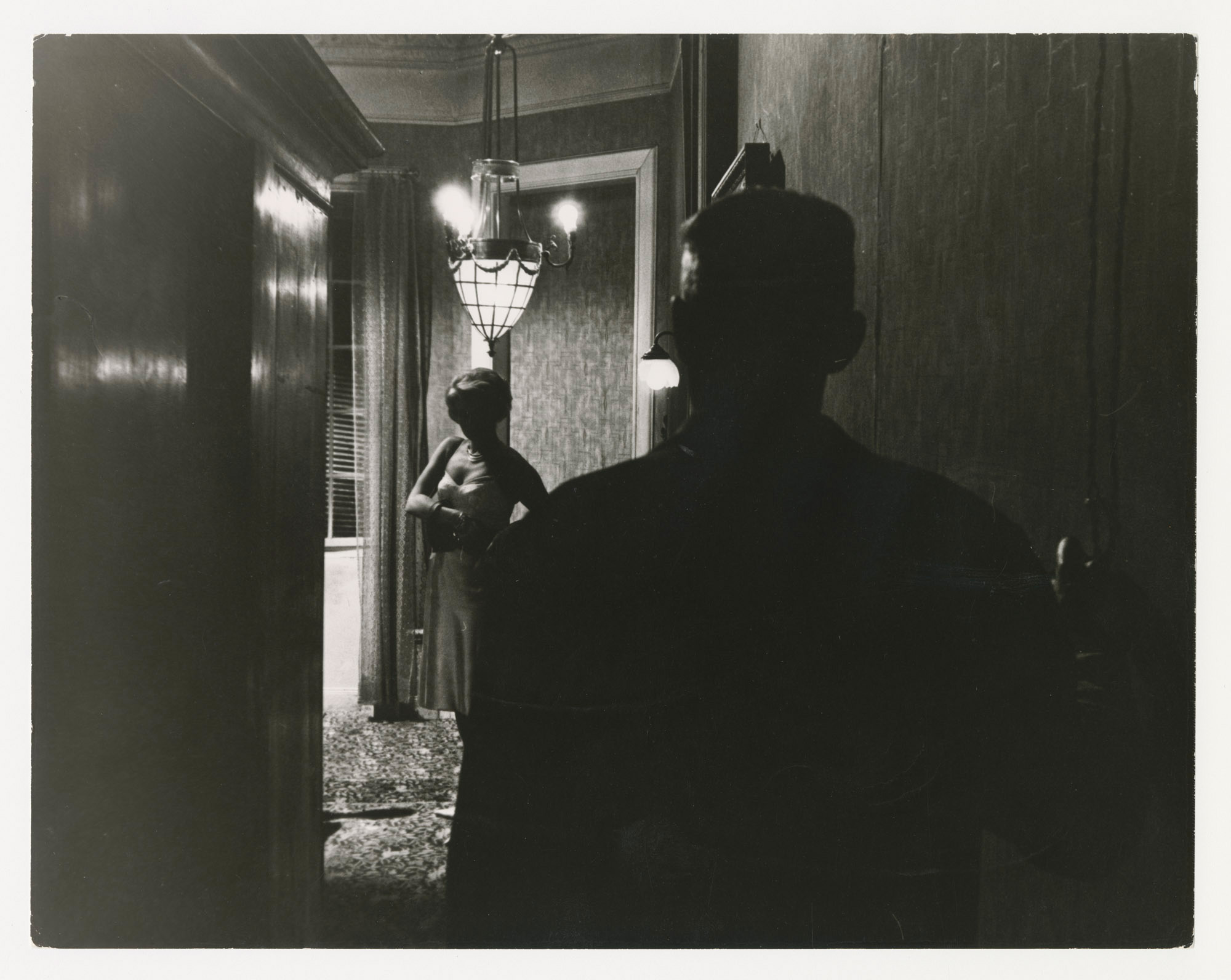

It’s raining in downtown São Paulo when our hero, now aged 14, enters stage right once again. One day, skipping class, Kogan dives into the rundown cinema, Bijou, on Praça Roosevelt, to seek shelter from the elements. What he saw on that fateful day would transform his life forever. Screening at Bijou was the third of Ingmar Bergman’s trilogy of films on the loss of religion and faith, The Silence.

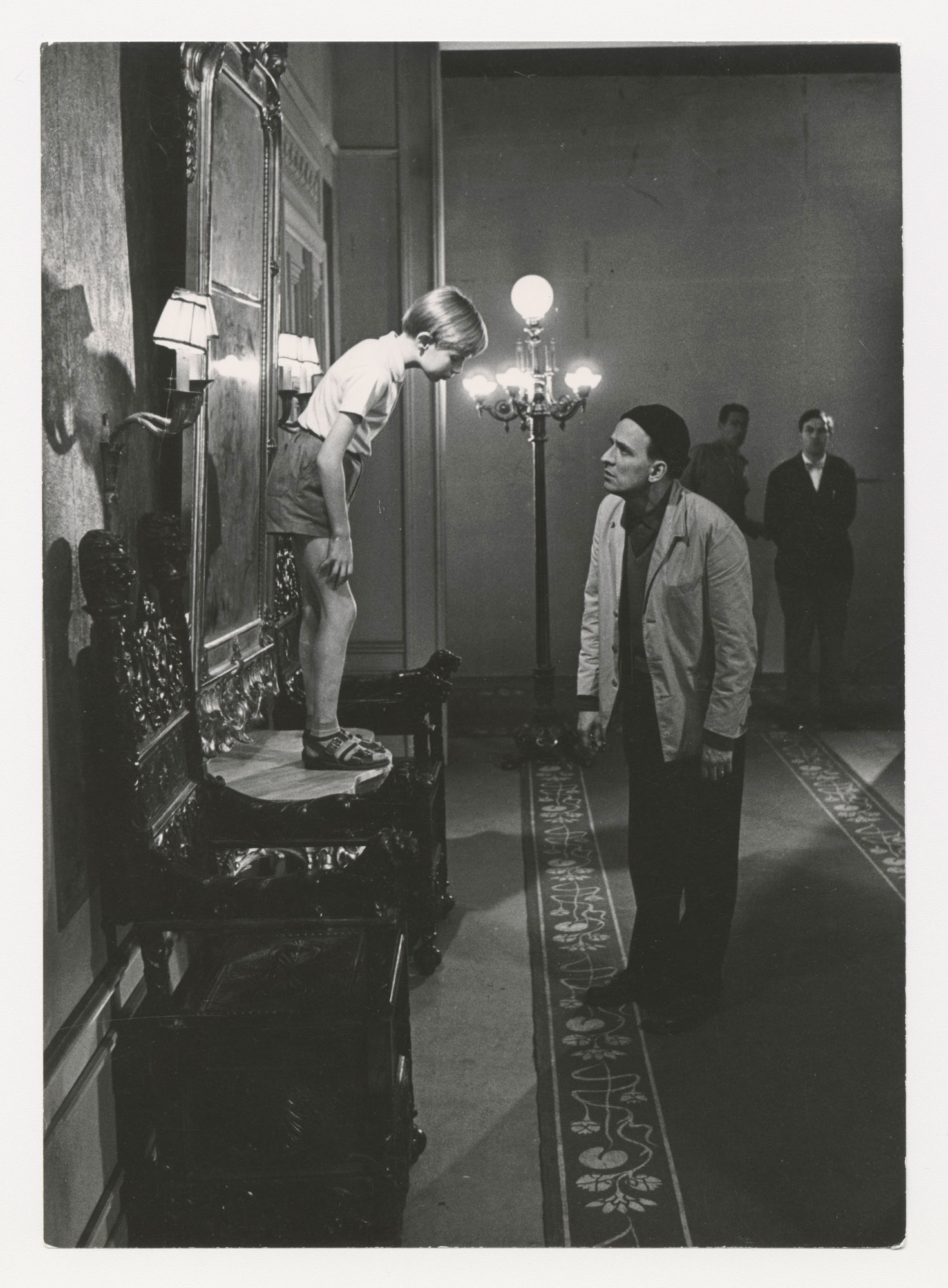

‘I discovered in that moment that something else exists in the world, real poetry. This was a kind of epiphany,’ says Kogan about the profound impact that the chance meeting with the film’s protagonist, a perplexed ten-year-old boy, Johan, had on his life and later career. ‘It changed everything for me because I saw myself on the screen. That was the boy in the film. I identified with every element of Bergman’s film. The film in black and white, the anger, anguish, loneliness. Everything that I was feeling at that moment, or from the day my father died, until this point. When I left the movie, my life became technicolour again. This moment would be the first moment of the rest of my life.’

His father may have been responsible for his early fascination with the form and function of buildings and the possibilities of a career in architecture, but, kissed by the silver screen, it was the cinematographic creativity of filmmakers, first Bergman and later Federico Fellini, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard and Andy Warhol, that shaped the type of architect he would become.

‘When I left the movie, my life became technicolour again’

Marcio Kogan

Throughout his architectural studies at Mackenzie Presbyterian University in São Paulo, and in his early twenties, he split his time between his fledgling architecture practice and making short films with his friend and kindred spirit, Isay Weinfeld. The pair produced 13 short films together between 1978-1987. It was the financial failure of their only feature-length film, Fire and Passion, in 1988 that finally forced them to quit film and focus instead on creating homes with celluloid qualities. ‘The film was a disaster,’ says Kogan. ‘It was then that I decided to be an architect 24 hours a day.’ Cinema’s loss would be architecture’s gain.

Anyone who has seen or visited one of Kogan’s panoramic palaces, stayed in one of his scenic hotels or shopped in one of his illuminated stores, will have been struck by the horizontal, cinematographic narrative running through his work. As Wallpaper’s architecture & environment director, Ellie Stathaki, writes in her essay in Studio MK27’s recently released monograph of its work, published by Rizzoli, ‘The relationship between architecture and the moving image is at the heart of the practice’s visual storytelling and world-building. Seeing architecture not as a static element but as a part of a wider universe that encompasses movement, sound and light, Studio MK27 creates designs that become inherently multi-dimensional, spaces to be felt far beyond aesthetics and the perception of a structure as a still image.’

‘I observe the proportions of a project as if I were looking through the lens of a widescreen movie camera’

Marcio Kogan

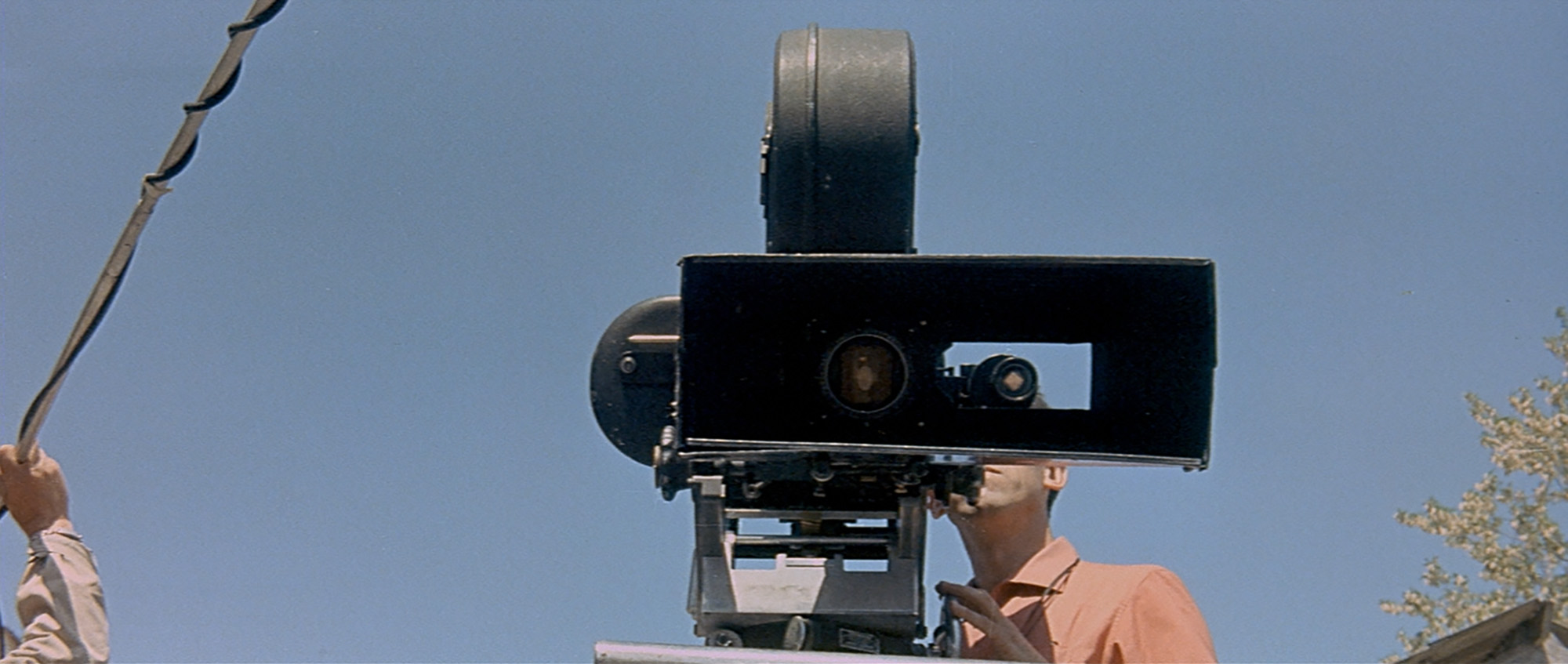

The architect himself believes his formative foray into the world of make-believe, of lights, cameras and action, has served him well when it comes to crafting a magical world of warm, minimalist architecture. ‘I see many coincidences between architecture and cinema,’ he says. ‘They are achievements that, telling a story, have a beginning, middle and end, and must create emotion. I observe the proportions of a project to a fault as if I were looking through the lens of a widescreen movie camera. It is a cinematographic frame.’

Furthermore, he encourages creative collaboration on all of Studio MK27’s projects and has, since the studio’s opening in 1978, sought to reproduce the teamwork and multidisciplinary perspectives required to make great movies, working with as many as 50 collaborators at a time. ‘The teamwork of filmmaking created a way of working in the office that’s different from what you find elsewhere,’ he says. ‘Everyone can work on a new project with me, from an intern to the directors. In the beginning, it was a kind of chaos, but now it works very well.’

All Studio MK27 works kick off with a brainstorming session that seeks to identify the ‘philosophy of the project’ and ends with credits rolling for everyone involved. Multiple teams are often formed to work on different solutions and later convene to compare and work together to select the best approach. In the conceptual stage, Kogan often immerses himself in a new project by throwing himself like a method actor into the role of a protagonist enjoying (or often not enjoying) the house in the future.

He has envisioned his work from the perspective of a bird complaining to the architect about the death of one of his flock, bees trampled underfoot by clumsy architects, or a cat exploring the liminal spaces created by his intelligent blurring of interior and exterior spaces. He often finds himself fielding imaginary complaints from angry clients as part of his method of troubleshooting his way to perfection. Many of these internal conversations and characters reveal insights that are incorporated into the work. Some have later featured in the short films the studio now produces to showcase its projects or to contextualise the sumptuous furniture lines produced for Italian manufacturer Minotti.

Almost 50 years after Bergman’s The Silence first brought colour back into the life of our 14-year-old hero, it returned once again to speak to Kogan as a 67-year-old professor in Milan. In 2018, he set a task to one of the workshops he produces with his long-time collaborator, Filippo Bricolo, and received a remarkable response from one student, Vladimir Boaghe, who reached deep into the soul of our young protagonist(s) – Johan and Marcio – to produce a book comparing cinema and architecture, and comparing The Silence and Marcio Kogan.

‘When you are a teacher or professor, sometimes you don’t just want to transfer your knowledge to the student but to learn something, too’

Marcio Kogan

In the book, the student paired scenes from Bergman’s movie with elements of Kogan’s architecture to draw a creative arc through his remarkable body of work back to his chance discovery of the silver screen. ‘When you are a teacher or professor, sometimes you don’t just want to transfer your knowledge to the student but to learn something, too,’ says Kogan. ‘This is the most perfect example. It’s not so easy to give a very clever gift. This one I needed maybe one hour to understand the power of it. It’s like looking into yourself.’

While Johan is present in many of the images from Bergman’s masterpiece, it’s easy to imagine a young Kogan in the other frames, pointing his toy gun at the scenes and imaginary characters cast in his architecture. The subliminal pairings of the book led to a profound reflection by Kogan, sparking the creative inspiration for the pages he has curated for his guest editorship of Wallpaper*, as well as the desire to use filmmaking to present the studio’s work to the world.

Alongside images selected by Boaghe, Kogan and his team have chosen stills from short films and photography of Studio MK27’s works that tally with those of his other filmmaking heroes, Jacques Tati and Jean-Luc Godard. Together, they provide a revealing insight into half a century of carefully choreographed coincidences playing out between Studio MK27’s two leading actors – filmmaking and architecture.

Film and architecture: through the lens of Marcio Kogan

In his section of Wallpaper’s October 2024 issue, guest editor Marcio Kogan paired film stills from some of his favourite movies with photography from his own work, highlighting the subliminal connections in his way of working and the duality of film and architecture in his approach.

Screening 1: The Silence, directed by Ingmar Bergman (1963)

When, in a moment of unadulterated synchronicity, a 14-year-old Marcio Kogan discovered the moody black-and-white feature film, The Silence, directed by Ingmar Bergman, it changed everything for him. That fateful matinee transported the brooding teenager from a dark place, still grieving the loss of his father, to a technicolour world of art and poetry.

‘In the case of Bergman, it was my life at that moment,’ says the architect of his discovery of the Swedish director’s work and his immediate identification with one of the film’s main characters. ‘After I saw his movie, I belonged once again to humanity in that, for me, it gives me a sense of art, this is what I can see, that there is poetry. This is what attracts me to his films,’ says Kogan.

Released in 1963, The Silence tells the story of a ten-year-old boy, Johan, travelling through a fictional European country in the aftermath of the Second World War with his mother, Anna, and her sister, Ester. It is the last film in a trilogy by Bergman that the director says was his way of celebrating the ‘saving force of love’.

‘My basic concern in making the trilogy was to dramatise the all-importance of communication, of the capacity for feeling,’ he later said about the three films, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light and The Silence. ‘They are not concerned – as many critics have theorised – with God or his absence, but with the saving force of love. Most of the people in these films are dead, completely dead. They don’t know how to love or feel any emotions. They are lost because they can’t reach out to anyone outside of themselves.’ The work of the child actor that plays Johan – Carl Jörgen Lindström, who was born less than a year before the architect – spoke deeply to Kogan.

In a book gifted to the architect by his student Vladimir Boaghe in 2018, the latter explores the depth of the film’s impact on Kogan by pairing scenes from it with details from the architecture of Studio MK27. ‘How can such a state of mind be an inspiration for spaces so full of joy and life as the houses he designs?’ says Boaghe. ‘This analysis tries to highlight the strong connection between the projects and the framing, the lights and the gestures we can find in the movie, pointing out the evident quotes and the unconscious influences we can recognise in his works and in the way he shows them.’

The title of the publication, Hadiak, refers to the last word of the film uttered by the child protagonist, which in Bergman’s fictitious language translates to ‘soul’, something that Boaghe argues is a ‘constant presence in his projects and what really characterises Kogan’.

Screening 2: Playtime, directed by Jacques Tati (1967)

The comic escapades of Monsieur Hulot, played by Jacques Tati himself, revolve around struggles with technology and the daily problems of living in an increasingly complex world shaped by modern architecture. The French director’s films are among Kogan’s favourites, even though he disagrees strongly with Tati’s view that ‘geometrical lines do not produce likeable people’, the modernist Villa Arpel in Mon Oncle evoking fond memories of the house his father built for the family in São Paulo.

‘Sometimes I think Tati copied my father’s project. Both houses had a lot of electronics; my father decided at the same time to create a house of the future. It was a radical project, but not everything worked. My father decided to design everything, from the tables to the art and the architectural project itself. And, of course, this kind of thing, when you are created in this environment, it influences you a lot.’ And while there are references in his work to Villa Arpel, Kogan does everything he can to avoid the impracticality of dedication to superficial aesthetics and gadgets over the necessities of daily living.

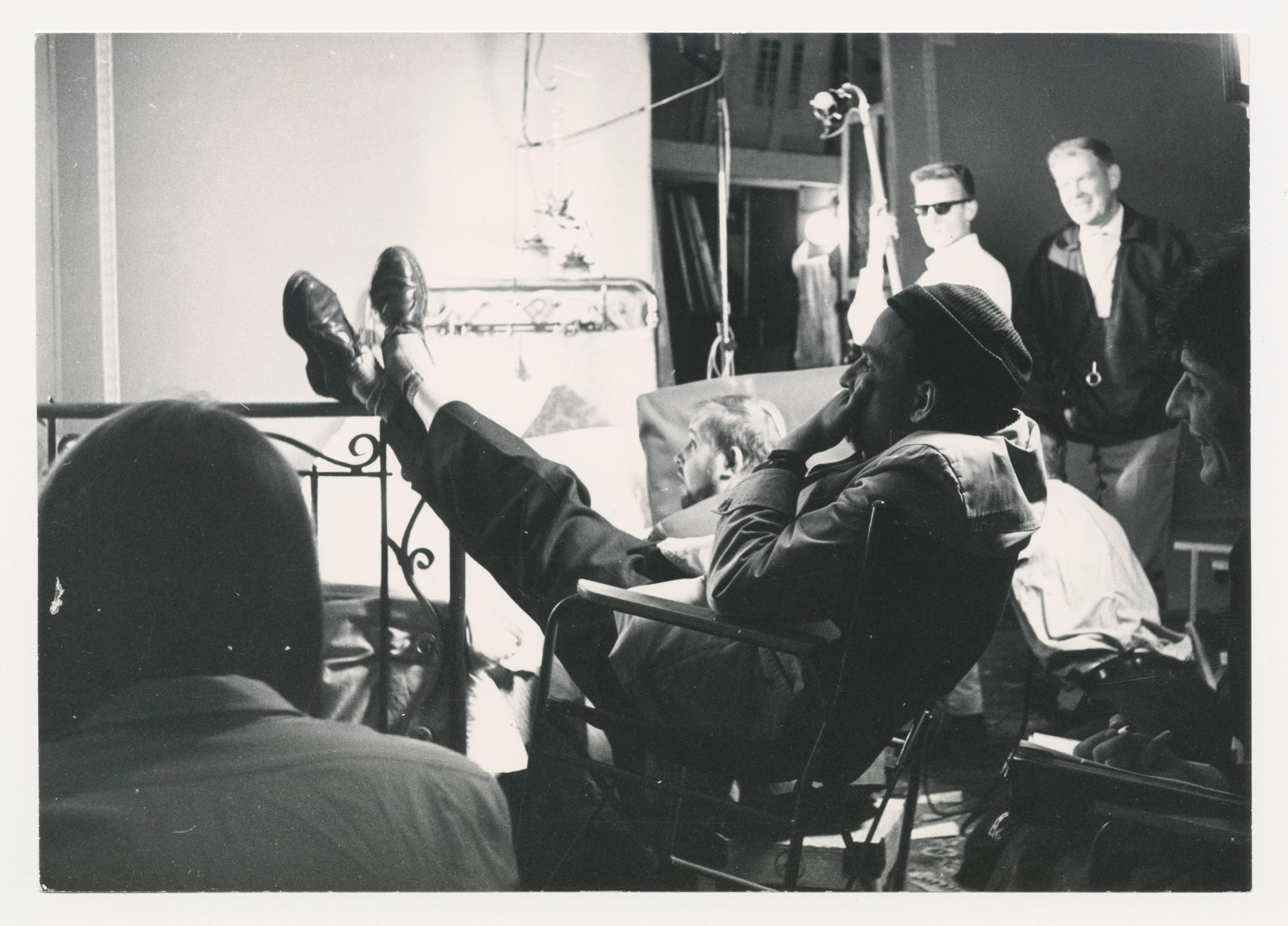

Perhaps Kogan’s favourite film, Playtime, is another that pokes fun at the French modernist architects that shaped much of the built environment in the 20th century. For the 1967 release, Tati constructed a modernist Parisienne quarter as a movie set and shot it on 70mm film stock at great expense. While there are plenty of references to Tati’s architectural aesthetic, in Kogan’s work, once again, it’s the mutual sense of humour that brings him back to the film so frequently.

‘People want something serious when it comes to building their dream home. It’s very expensive to be funny’

Marcio Kogan

‘We shared a way of seeing the world through critical humour. In architectural thought, maybe we’re on opposite teams, but this doesn’t matter. What matters is life, as our architect Oscar Niemeyer said.’

Rewatching the opening night of the restaurant unravel in Playtime brings outboth his obsession and sense of fun, he admits. ‘There is one moment in the film that I think happened every week with me,’ he says. ‘It’s the scene where he’s visiting a family in the glass apartment where you can see what’s going on inside. He leaves the family, says goodbye, and 30 minutes later, when the owner of the apartment goes to walk the dog, he’s still stood there because he cannot find the button to open the door. This kind of thing always happened in São Paulo.’

Alas, for someone with such a strong sense of humour, there’s arguably not a lot of room for comedy in architecture. The only humorous piece he can think of in Studio MK27s body of work is the cement apparently dripping from the façade of his first project, the firm’s offices built in the Cerqueira César neighbourhood of São Paulo in 1978. ‘I mean, people want something serious when it comes to building their dream home,’ he says. ‘It’s very expensive to be funny.’

Screening 3: Le Mepris, directed by Jean-Luc Godard (1963)

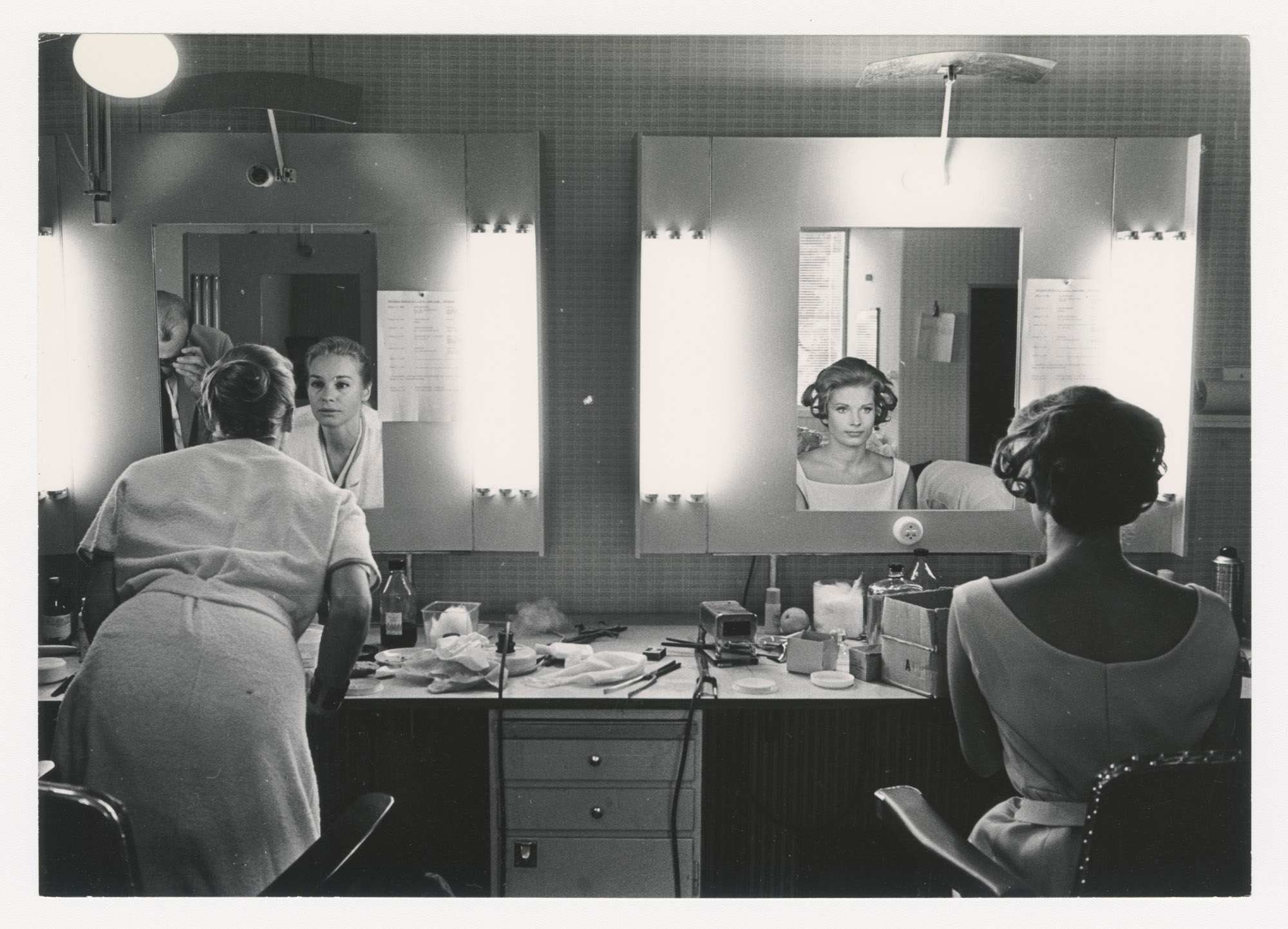

Based on Alberto Moravia’s 1954 novel II Disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon), Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 movie, starring Jack Palance and Brigitte Bardot, is set against a remarkable Italian backdrop.

A terribly sad story of the loss of love, the film was made largely in the Capri landmark, Casa Malaparte.

The film has been interpreted as Godard’s own reflection on the death of cinema, the start of the end for a golden era in filmmaking.

‘This house is incredible. It wasn’t designed by an architect. It was designedby a poet,’ says Kogan.

‘I think it’s always the relationship with water, maybe with thesea. I think this and you have empty space, big windows and a stronger relationshipwith the view on this kind of film. It’s very much related to our project in Paraty.’